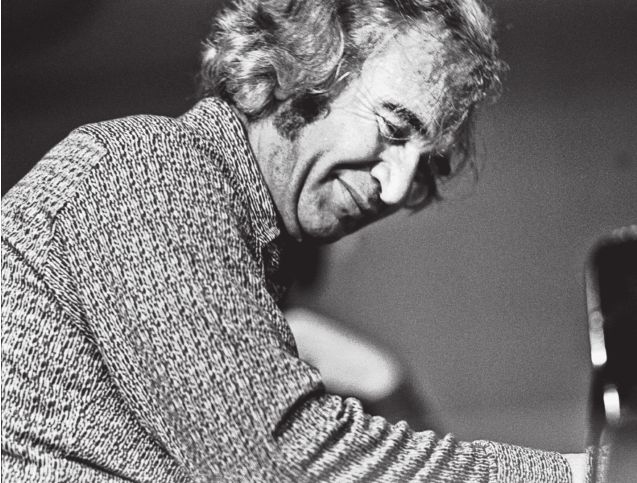

Pilgrim’s progress

Dave Brubeck made jazz cool

DYPEPSIANA | James Krohe Jr.

I hear you’re mad about Brubeck I like your eyes, I like him too He’s an artist, a pioneer We’ve got to have some music on the new frontier – “New Frontier” by Donald Fagen

When I was in high school I had a taste for jazz that, like every else about me at that age, consisted of enthusiasm almost perfectly uninformed by experience. My state-worker father had borrowing privileges at the old state library, and out of curiosity I checked out a jazz version of a wine sampler in the form of a compilation LP consisting of tracks from each of the winners of the first annual Playboy Jazz Poll in 1957. On Side 4, Track 1, was a tune called “Pilgrim’s Progress” by the Dave Brubeck Quartet, which had been recorded live the previous August at a festival in Stratford, Ontario.

I kept our portable record player on the stool I used as a bed table and pulled it as close I could to my pillow. That way I could hear it without disturbing the rest of the family – and because with my head thus wrapped in sound, the rest of the family couldn’t disturb me, and I could fly away and spend 9 minutes and 13 seconds in the audience in Ontario on a warm summer’s evening.

I made the trip many times. Over the years since, I thought of that track the way a guy thinks of an old girlfriend, if he’s lucky enough to have had a girlfriend whose company he liked that much. A couple of years ago I learned that the track had been reissued on CD. Hearing it again was like meeting an old flame, only without having to listen to the dull stories of the years in between. Best 12 bucks I ever spent.

To teenagers like me in the Springfield of the 1960s, The Music Shop on Fifth and the record department in the basement of Sid Ackerman’s store on Adams were, like Harry Potter’s Platform Nine and Three Quarters, portals to magical places. Among other reasons, that’s where I bought the LPs by the Brubeck quartet that for me were heavily laden with treasures from faraway worlds.

In the series of albums that got too much prominence in his obits, he essayed tunes based in what are to Western ears exotic and tricky rhythms from Eurasian folk

music, Maori drums and Turkish street musicians that Brubeck heard while

on State Department cultural tours.

From

their liner notes I learned that Brubeck had studied with Darius

Mihaud. (Where’s the encyclopedia?) His classical training made him

suspect in the surprisingly closed community of jazz, which was

determinedly unschooled. As for the album covers, the time series LPs

featured works by abstract expressionists (what’s that?) Joan Miró

(never heard of her), Franz Kline and Sam Francis, each a painter new to

me.

As the lyric

quoted above suggests, Brubeck was an icon of the 1960s, more

specifically the early ’60s of Kennedy and jet travel and stereo sound,

when it was briefly hip to be young and cosmopolitan. Call it white,

call it West Coast, call it modern – Brubeck’s jazz for us was about

opening up to the world at a time when black jazz was beginning to close

up on itself.

There is some truth to the sneer that Brubeck made jazz safe for white college boys.

(Those college boys, all

growed up, seemed to have written every encomium I read about him.) Jazz

is expressive of the subculture of those who play it, as two minutes of

listening to any Latino jazz player will make clear. Whites did the

same, and the subculture they were both adapting to and creating in the

1950s was celebrated and, to some extent, created by the original Playboy magazine.

Oddly,

given the role that the magazine played in marketing it, the mostly

West Coast jazz of the period was jazz without sex and without danger.

Dressed in suits and having the stage manner of accountants at an audit,

the Brubeck band was one of the first to present jazz as if it really

was what so many critics said it was, which is America’s classical

music.

On Dec. 5

Brubeck died, as pianists in their nineties tend to do. He was extolled

as a good man and a brave leader of an integrated combo in a

still-segregated America, and was also an underrated composer of tunes.

Too few obits mentioned his service in giving a platform to alto player

Paul Desmond; I occasionally find myself thinking of Brubeck as

Desmond’s piano accompanist – which the modest Brubeck, to his credit,

often did himself.

It

mattered to me not at all that he did little of lasting musical

influence in the final years of his life. What mattered was his

influence on me in the first years of mine. For a lot of us growing up

in his heyday, he was one of those teachers you never forget.

Contact James Krohe Jr. at [email protected]