Skin City

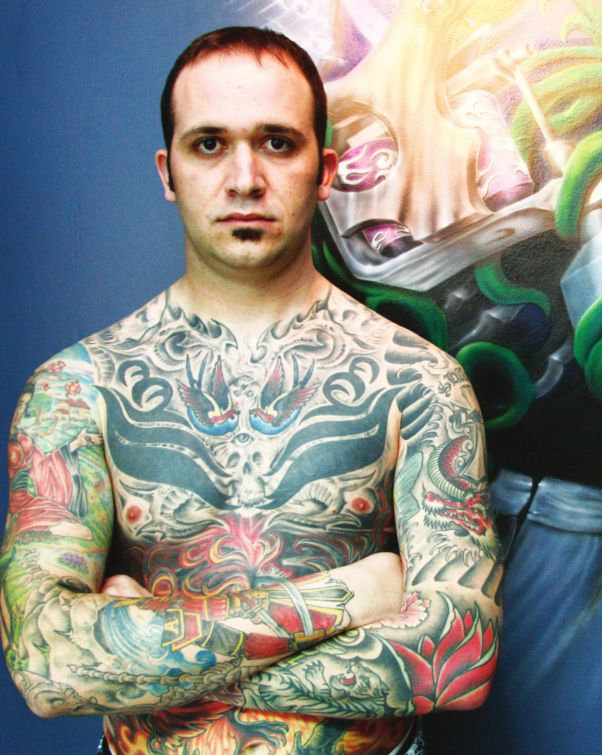

Tattoos come of age in Springfield

ART | Patrick Yeagle

Why would someone voluntarily undergo several hours of a needle stabbing them several thousand times per minute? The simple answer is for the sake of art, but the long answer is a bit more complicated.

Thanks to athletes, celebrities and TV shows, tattoos have gone from taboo to typical over the past 20 years. What started as a form of rebellion in the United States has become more of a personal fashion statement and, despite Springfield’s reputation as a holdout against style, this city is well stocked with both the inked and the inkers.

Tattoo artists in Springfield say the industry is healthy – both from a business perspective and from a disease-control perspective. Even upstanding professionals – doctors, lawyers, university professors and business owners – around town now sport tattoos, the last class of people who would have taken on such potentially career-ending marks a couple of decades ago. Still, tattoos are a gray area in the cultures of business, religion and society at large – common enough to be tolerated, but best kept out of sight in some circles.

A tattoo primer The practice of tattooing dates back thousands of years. The oldest known examples of tattoos are the handful of dot and line patterns on Otzi, the 5,700-yearold mummy found in the Austrian Alps in 1991. Tools found elsewhere and believed to be tattoo implements have been dated as far back as 10,000 B.C. Numerous ancient and modern societies around the world had or have their own distinct tattoo cultures, but almost all revolve around tattoos as symbols of life events or life choices.

Some cultures like the ancient Chinese and ancient Romans used tattoos to brand slaves and criminals. Ancient cultures like the Vikings and Celts used tattoos to proclaim rank or status, and some indigenous tribes around the world continue the practice. Tattoos have been used to commemorate a birth or death, a first hunt or first battle, marital status and even to advertise marketable skills like weaving.

While tattoos have played prominent roles in many cultures, they carry a stigma for some people. Many Jewish people still alive today bear numeric tattoos forced upon them as identification in Nazi concentration camps during World War II. In American society, tattooing first took hold among “unsavory” characters like sailors, outlaws and circus performers, creating a negative association that was compounded by the danger of blood poisoning, hepatitis and other blood-borne diseases.

That danger has largely disappeared from the modern tattoo parlor. The old archetype of the dingy hole-in-the-wall shop littered with used needles and filled with strung-out ne’er-do-wells still exists, but it has been upstaged by clean, well-lit businesses that happily abide by health regulations and even carry liability insurance. While some tattoo practitioners – the legitimate ones hesitate to even call them “artists” – do still run underground (i.e. illegal) tattoo shops, they are typically fly-by-night operations in someone’s home using equipment that may or may not be sterilized.

That danger has largely disappeared from the modern tattoo parlor. The old archetype of the dingy hole-in-the-wall shop littered with used needles and filled with strung-out ne’er-do-wells still exists, but it has been upstaged by clean, well-lit businesses that happily abide by health regulations and even carry liability insurance. While some tattoo practitioners – the legitimate ones hesitate to even call them “artists” – do still run underground (i.e. illegal) tattoo shops, they are typically fly-by-night operations in someone’s home using equipment that may or may not be sterilized.

Glenn Sisco, a tattoo artist of about 20 years currently at Outkast Tattoo Company, 1535 Wasbash Ave., says he knows of at least one illegal tattooist in the area. Sisco says some of the rogue tattooist’s clients have later come to him for coverup art.

“It bothers me that people are out there doing shoddy work and giving us all a bad name,” Sisco says. “But I don’t mind the extra business when his people come to me to fix his mistakes.”

Brian McCormic, a tattoo artist at The Artist’s

Edge, 2110 North

Grand Ave. E., says some illegal shops blatantly flout the law – even

advertising on Facebook – because they don’t fear any repercussions. He

says he and his fellow tattooists at The Artist’s Edge are planning to

push for tighter regulations in Springfield to cut down on illegal

shops.

“It’s not even

about me losing business,” he said. “I would rather you pay me a hundred

bucks to do it right the first time than have you pay me a hundred and

fifty or two hundred bucks to fix someone else’s mistakes. We see really

bad work coming in that was done in someone’s basement or kitchen by

untrained people. What’s happening is you’re getting people who don’t

know anything about sterilization, and it’s a real public health issue.”

State

law requires tattoo shops to be licensed, and each artist must have

training to prevent the spread of blood-borne pathogens. Shops must keep

client records and have an infection control plan in place.

Modern

tattooing is usually done with a motorized or air-driven needle. While

tattooists in bygone eras often reused needles from client to client,

modern shops throw needles away after one use and use an autoclave to

sanitize the tattoo machine. (Don’t call it a “gun,” though.) Artists

wear fresh gloves for each job and even have a “secret” handshake – an

elbow bump – that prevents their hands from being contaminated while

tattooing.

Sisco says the regulations and precautions have helped the tattoo industry overcome its formerly poor reputation.

“They’ve legitimized tattooing,” he says.

“It’s safe now, and I think that’s good for the industry.”

Cultural

acceptance The legitimization of tattooing was helped along by

celebrities and TV shows, says Nicholas Jones, a tattoo artist at New

Age Tattoos, 2915 S. MacArthur Boulevard. Jones says the prevalence of

tattoos on athletes and movie stars brought tattoos into the public

consciousness, but shows like TLC’s “Miami Ink” turned tattooing into a

“rock star” culture.

“It

brought the experience to the average person,” Jones said. “It showed

people who may never consider a tattoo that tattoos have meaning, that

they’re fun and not just about rebellion.”

Styx

Killion, owner of Styx Unlimited Tattoo Emporium, 1313 Stevenson Drive,

started tattooing about 20 years ago and opened his shop in Springfield

about six years ago. He says tattoo shows also provided a window into

the world of tattooing.

“They’ve

definitely opened the eyes of people who were too scared to walk into a

shop, expecting the old sailor and biker style with people behind the

bar shooting up and getting drunk and tattooing each other,” he says.

“It’s nothing like that. They see it on TV and it’s much more classy

than that now.”

Mark

Lehmann, owner of Outkast Tattoo Company, says since he started

tattooing about 13 years ago, he has seen several changes, including

equipment improvements, proliferation of shops and even the types of

people getting tattooed. As more and more people “get ink,” Lehmann

says, tattoos have become more accepted by employers, though some people

still cover their tattoos at work – sometimes by choice and sometimes

due to employer dress codes.

“I’ve

tattooed people from every ethnicity, religion, gender, age, profession

– you name it,” he said. “I’ve done tattoos on clergy, doctors…I even

did a full body suit on a professor. Most of those people, though, you

wouldn’t even know they had tattoos.”

Tattoo artist Terry Brown manages DreamTime Tattoo and Body Piercing Studio, 136 W. Lakeshore

Dr., and Fat Cat Tattoo and Body Piercing, 716 N. Dirksen Parkway. His

father, Terry “Solo” Hanyes, opened the shops about 13 years ago but had

tattooed for about 34 years. Brown’s mother, Cindy Lou Haynes, still

owns the shops and continues to tattoo at DreamTime.

Brown says he often talks clients out of getting tattoos on parts of the body that can’t be easily covered, like the neck.

“Don’t

put it somewhere you can’t hide it,” he advises. “There’s still a lot

of stereotyping that comes along with tattoos, so I sometimes talk to

people about the placement before we do it.”

For jobs in which workers come into contact with the public, tattoos should be inoffensive or easily hideable, he says.

For jobs in which workers come into contact with the public, tattoos should be inoffensive or easily hideable, he says.

That

fits with the guidelines used by Memorial Medical Center. The

hospital’s job recruitment website lists a tattoo-related tip in a list

of interview do’s and don’ts: “Don’t… wear dangling jewelry, body

piercings (or) visible tattoos,” while a similar page advises applicants

to “Cover tattoos with clothing if possible.”

Michael

Leathers, a spokesman for Memorial, says the hospital doesn’t prohibit

tattoos, but ink that is “offensive, excessive or distracting to a

department’s function” should be covered at all times. That

determination rests with each department manager, Leathers says.

Better

art and bigger meaning When Kevin Veara first started tattooing about

20 years ago, there were only one or two tattoo shops in Springfield,

each with only one or two artists. The number of shops has now grown to

eight, with most shops employing several artists. Veara is the owner of

Black Moon Tattoos, 1009 W. Edwards St., and he says the increase in

shops and artists has raised the bar for good ink. Veara says shops used

to specialize in tracing what’s known as “flash” – canned designs from a

binder that got reused countless times.

“When

I first started, the shops were just sticking their toes in,” he said.

“Ninety percent of their business was on two sheets of flash, and they

didn’t even try to draw custom designs. Now there are young kids around

town doing incredible, original work that just makes me say, ‘Whoa.’ ”

Styx Killion says the art has definitely progressed since he started, as

well.

“It’s much more

of an art form now than it was back then,” Killion says. “It’s way more

intricate designs, more of a painting style instead of just the

traditional line work and some colors like back in the day – the old

‘Popeye’ tattoos.”

Mark

Lehmann at Outkast Tattoo Company says TV shows about tattoo shops

helped push the transition from flash to fullcustom designs.

“They

gave the public an idea of what a quality tattoo looks like,” Lehmann

said. “There are a lot of tremendous artists putting their craft out

there now.”

The meaning behind tattoos within American culture has also shifted from rebellion to personal expression, Lehmann says.

“I

would say back in the day, tattoos had a bad reputation because there

were a lot more people interested in following the main path,” he said.

“There are a lot more people now interested in following their own path.

It’s a way to show your true colors and be an individual.”

Brian

McCormic at The Artist’s Edge says the rebellion aspect combines with

the pain of tattooing – which he describes as a “stinging sensation” –

to produce a sort of “high” in the mind of a tattoo recipient.

“You have

the same physical reaction to a tattoo that you would have from being

scared or from running a marathon,” he said. “Your body starts producing

natural endorphins to deal with the pain, which is actually pretty

minimal. At the end of the tattoo, the pain pretty much stops, but the

endorphins are still there. It’s an adrenaline high, so when you walk

out of the shop, not only do you feel like you did something you’re not

supposed to and your parents are going to be pissed – that feeling of

‘Yeah, I’m a bad man’ – but you also get that chemical feeling of ‘Yeah,

I want to conquer the world.’ Those two elements are what ‘addict’

people to tattooing. It’s a sense of freedom.”

Kevin

Veara at Black Moon Tattoos says he has tattooed many people who wish

to commemorate a period of personal growth, perhaps overcoming a

traumatic event like a death or divorce.

“It’s a way to handle grief,” he said.

“It

makes sense to them. I think most people who get tattoos are actually

pretty conservative, and I can tell when people are really stepping

out.”

But Veara cautions that getting someone’s name tattooed is rarely a good idea.

“Sometimes people come in and want their spouse’s name, but we get to talking,

and

you find out they’re just grasping at straws,” he says. “I’ve even

covered up one name with another. My advice is to never get a name

unless it’s your kid’s name.”

For

many tattoo artists, creating the art itself is motivation enough to

tattoo, but each artist has his or her own personal reasons, as well.

“It’s

really satisfying because I learn something new all the time,” said

Nicholas Jones at New Age Tattoos. He says he also enjoys meeting new

people and tattooing them. His favorite so far is a 91-year-old

grandmother who got a small flower tattoo.

Brian

McCormic at The Artist’s Edge admits he enjoys the personal rebellion

of tattoos, but it also broadens his life experiences.

“I’ve

definitely taken stock of the American public from this job,” he said,

adding that he has worked in several different states. “I don’t go out

and try to meet people, but when people walk through the door and I

spend two hours with them, I learn something about somebody who I

probably never would have talked to before.”

Styx

Killion says he enjoys tattooing for the art, but he also likes the

satisfaction of “knowing that it’s going to be there long after the

people are gone.”

Glenn Sisco at Outkast shares that slightly morbid sentiment.

“I wanted to be part of everyone’s last five minutes,” he said. “When the parachute doesn’t open, my art will be there.”

Contact Patrick Yeagle at [email protected].