Scrumming in Springfield

The Celts are looking for a few good men

SPORTS | Bruce Rushton

It is easy to imagine the Springfield Celts as third-graders.

These are the guys who loved dodgeball, the ones who laughed and screamed “Whoa!” when balls found their mark in particularly violent fashion, the ones who pleaded for one more game before recess ended, the ones who didn’t notice when classmates cowered or developed sore throats necessitating trips to the school nurse, who never found anything wrong.

These guys were always up for smear-thequeer and at the bottom of the dogpile when the ball came loose. These guys didn’t bother with Band-Aids. These guys didn’t tuck in their shirts or get home on time.

These guys have not changed. It takes balls to play rugby – that is, perhaps, the sport’s oldest cliché, and it is true. There are women’s teams in big cities like Chicago and at a handful of universities across the land, but in Springfield, rugby is a case of boys being boys. Marriage, they say, is the leading cause of retirement from rugby, although debilitating injury and sheer age take their own tolls.

Rugby is played in the fall, spring and summer – only when the pitch freezes do ruggers hang their cleats. The cycle begins in February, when the Celts meet at Goals

Indoor Sports, an indoor soccer arena on North Peoria Road, for conditioning drills.

“They have a liquor license, so it’s good for us,” says Jim Carlberg, the team’s coordinator cum coach.

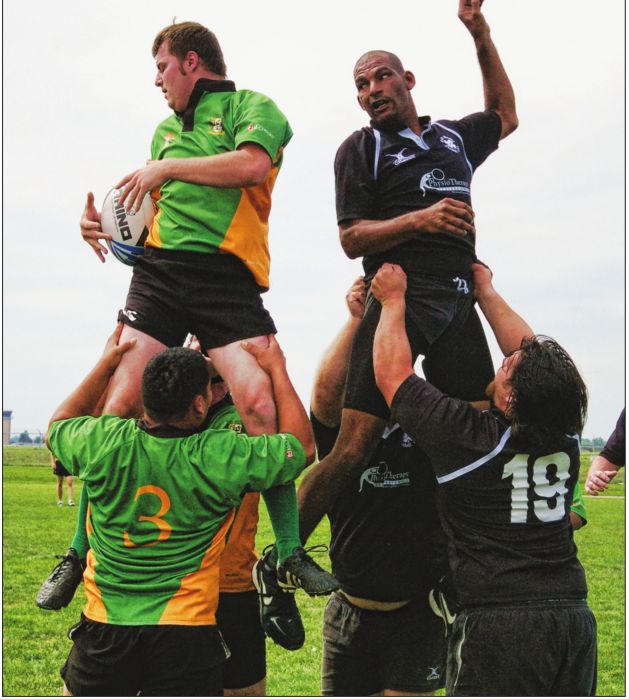

One of the biggest fraternities Tensions and expectations are high during this mid-September match against the Flatlanders, a team from Champaign. The Celts are looking for their first win in a long time, and the officials aren’t helping matters.

“That’s a bullshit call, sir!” Even in the heat of battle, Dave Schneller, a Celt whose playing career ended years ago, exercises proper etiquette as he shouts instructions to both players and officials from the sidelines. You can call a ref blind, you can say things about his sister. Just make sure you call him “sir.”

At the moment, Schneller believes a Flatlander is cheating by reaching into a huddled mass of players – it’s called a scrum – to grab the ball from the ground. You’re not supposed to use your hands until one side or the other pushes the opposition out of the way and the ball is clear of the scrum. Then, the scrum-half (yes, there are positions in rugby, just as in football) snatches the ball and either passes it to a teammate or runs with it himself.

If

there were a Springfield Rugby Hall of Fame, Schneller would be a

charter member. He started playing for the Celts in 1985 while attending

Lincoln Land Community College and became world class, playing for the

All Army Team after joining the military, then the All Services Team,

composed of the best players in all branches of the armed services.

Schneller

was playing for the Celts when his career hit sunset during a match in

St. Louis. He was tackling an opponent when a cleat dug in and nothing

else did. His right leg twisted until it snapped.

Carlberg,

who was present when Schneller went down, recalls his teammate’s foot

facing backward. Bone protruded. Nonetheless, Schneller after several

surgeries eventually returned to the field and played a few games with a

medically fused ankle, Carlberg says.

“He’s an animal,” Carlberg said. “He just has heart.”

Schneller will always be a Celt. “It’s honestly one of the biggest fraternities you’ll ever find,” he says.

It’s camaraderie as much as competition, according to Mike Gillespie, who has been playing with the Celts since 1998.

“The

goal is to win – it’s important,” Gillespie said. “But is it the

epitome of being out there? Not at our level. No matter what happens, 14

other guys have my back.”

At

this level, speed, strength and conditioning go a long way. If you are a

naturally gifted athlete, Schneller says, you will do well. It is not

unlike hockey or basketball, only with more lucky bounces: There aren’t

many set plays, and so players tend to react. At the sport’s upper

levels, where everyone is fast and everyone is strong, tactics matter.

“When I was in England, they called it a tackling game of chess,” Schneller says. “You’re thinking four plays ahead.”

In

Springfield, it is more a ruffian’s version of biathlon: sprint,

wrestle, sprint, wrestle, sprint, wrestle, with a fair amount of cussing

interspersed throughout. The basics are fairly easy to grasp. The

object is to get the ball into what would be the end zone in football;

in rugby, it is called the try zone, with a try worth five points. Kick

the ball between the uprights and you also get points, albeit fewer.

No forward passes, no blocking and, of course, no pads. The ball

can be advanced by kicking. No tackling when the ball carrier is in the

air, no tackling around the neck. The referee has wide discretion when

it comes to issuing penalties for conduct deemed unsportsmanlike. Player

safety, after all, is important.

Rules, naturally, are made to be broken.

Injuries?

Big deal. Midway through the first 45-minute half against the

Flatlanders, Celts captain Evan Brunner, who makes a fireplug look like a

beanpole, is churning upfield with the ball when an opponent charges in

upright instead of diving for torso. Wrong move. If anything, Brunner

gains speed while throwing a forearm that makes direct contact with his

opponent’s face, putting the Flatlander flat on his butt, where he

remains, dazed, for several seconds before slowly picking himself up.

Should

have been a red card, Carlberg admits, which would have put Brunner on

the sidelines and forced the Celts to play a man short for the remainder

of the game. The ref seems to be the only one who didn’t see it, and so

the lads play on. Afterward, Brunner makes no apologies.

“Sometimes,

you’ll have that,” says Brunner, a guard at Logan Correctional Center

who once played offensive tackle for the MacMurray College football

team. “They knocked my guy in the face, I retaliated.”

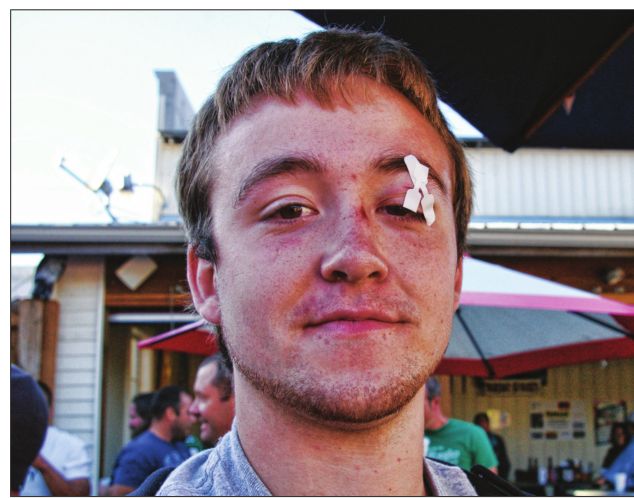

After

the game, Mason Powell, who got it in the face, resembles Rocky after

Mick cut him in the late rounds. One eyelid is sliced open, his nose is

bleeding from the side and Powell keeps a bag of ice over half his face

in a losing fight against swelling. He is not entirely sure what

happened there at the bottom of a pile. From the shape of his wounds, he

deduces that a Flatlander stepped on his head.

“See,” Powell says as he points. “One cleat there and another over here.”

Powell

is smiling when he says this. Seven neophytes from Lincoln Land

Community College, where the Celts have been recruiting, watch together

from a sideline bench. After the main event is over, they’ll give it a

go themselves in a brief. They look eager.

“If

I get hurt, I get hurt – I’ll heal,” says Michael Price, a 17-year-old

freshman at Lincoln Land. “If I break my arm, I’ll have a bad-ass story

to tell.”

A tradition of excellence Back in the day, the Celts were bad asses.

It

took a few years after the club was formed in 1975, but by the

mid-1980s, the Celts were a force, good enough that they once beat a

team from Notre Dame and traveled to Chicago and other big cities in

search of games.

The

Celts, the old-timers say, were like the Oakland Raiders of yore, a

physical team that usually found a way to win and made opponents think

twice before granting rematches.

“We

were mobile and mean,” recalls Rick Hamilton after the match with the

Flatlanders, which ends in a tie after a kick by the Celts in the dying

minutes goes wide right by a yard – it would have been worth three

points had it gone through the uprights. “We would have killed these

guys.”

At 57, Hamilton

is old enough to be his youngest teammates’ grandfather. He started

with the Celts in 1976 and still plays. Hard.

He is prone to

inserting himself in games in a way unimaginable back in the early days,

when no substitutions were allowed. No one dares tell him “no.”

Hamilton

is neither the swiftest nor the strongest, but he does not embarrass

himself. Younger guys can run all over the field nonstop. Hamilton

compensates with knowledge of the game that allows him to figure out

where a play is headed and get into position with a minimal amount of

energy. He does not shy from contact.

That

Hamilton has played in five decades speaks to a cold truth: The Celts,

who haven’t had a winning season in more than a decade, have grown old.

So few players were left just a few years ago that the Celts could not

field a team and so skipped a season or two. Three regulars are now in

their 40s. For the team to survive, fresh ruggers are needed. And they

are starting to show up.

Last

year, the average age on the team was 30, Carlberg says. Now, it’s in

the low 20s, the youngest team in a decade, thanks to recruiting efforts

at Lincoln Land and high schools, where rugby is gaining a foothold.

Much like its parent club, the Junior Celts, a team of players from

several local high schools that plays in the spring, lost every match in

their inaugural 2010 season. But it didn’t take long to get

respectable. In 2011, they finished fifth in the state. Last year, the

Junior Celts went undefeated until the state championship game, which

they lost to a team from Chicago.

Fueled

by youth, the Celts, Carlberg says, are on the cusp, despite losing

their first game, then tying their second match to the Flatlanders in a

match they probably should have won. Not so long ago, the Celts would

have fallen apart when opponents scored and argued among themselves,

Carlberg says. Now, they just keep trying.

Still,

there is some frustration. After dominating the first half of their

home opener against the Shamrocks, a team from the Chicago area, the

Celts fall apart in the second half, allowing two quick scores and

prompting Dominique Stewart – Dom to his teammates – to complain,

loudly, about Celts who don’t show up for twice-a-week practices at

Kennedy Park, the team’s home field. Excuses about work and family

obligations don’t cut it with Stewart as the other team gets ready to

kick a conversion, not unlike an extra point in football but worth two

points, after scoring a try.

“The

only way to way to get better at rugby is to play rugby,” Stewart tells

his teammates. “I work, too, and I come to practices.”

A

numbers game In just his third year, Stewart is fast, fearless and

intense – exactly the sort of player the Celts need. A former Junior

Celt, Stewart wrestled and ran track at Lanphier High School but now is

devoted to rugby. He spent last summer playing rugby in Colorado, making

ends meet as a cook so that he could learn and play the sport he has

grown to love.

“If we had more numbers, the Celts would be a whole different team,” Stewart says.

Stan Korza, who got his start in 1977 and played for 25 years

until his body could stand no more, recalled the days when the Celts had

enough players to field three 15man teams. Numbers, he said, are key.

“If you get a lot of guys, you have more guys to choose from,” Korza said.

There

are signs of hope for a team that lost every game last year. The Celts

are competitive this season, and more guys are turning out, enough to

allow a 45-minute match between reserve players after the main game with

the Flatlanders. Half the players have never played before, and their

grasp of the rules is tenuous at best.

Veterans

say the attrition rate is 50 percent or more for new players, but they

are nonetheless welcomed, both at games and after-contest parties at

Weebles, a North Peoria Road tavern with a beer garden that is taken

over by players from both teams after on-field hostilities end.

Imbibing

with the opposition after matches is a time-honored tradition in rugby,

as are bawdy songs that involve detailed descriptions of unnatural acts

involving priests, pregnant women and puppies belted out at top volume.

As pitcher after pitcher of keg beer disappears, the singing begins.

“You get drunk with the guys you just fought,” Hamilton says. “It’s the most fun game I’ve ever played.”

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].