No jackpot

Video gambling gets off to a slow start

GOVERNMENT | Bruce Rushton

The best way to curb gambling might be for the state of Illinois to legalize it.

The going has been slow since lawmakers more than three years ago approved video gambling outside casinos. Only last spring did the state gaming board start accepting applications from businesses, fraternal organizations and veterans groups for licenses to have video gambling on their premises. Fewer than 350 of those applications have been approved. The application backlog stands at more than 3,000.

State Rep. Rich Brauer, R-Springfield, blames the gaming board for delays.

“To me, it’s very frustrating that the state is so unorganized that a fairly basic bill takes over three years to implement,” said Brauer, who voted in favor of legalization.

It’s not necessarily the gaming board’s fault, according to Gene O’Shea, board spokesman.

A lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of the statute that legalized video gambling delayed implementation, O’Shea said. The legal challenge ended more than a year ago when the state Supreme Court upheld the law. In 2010, the gaming board reopened bidding for a statewide computer system to track wagering and money after an unsuccessful bidder argued that the bidding process had been botched. Gaming officials have also complained that lawmakers did not provide sufficient money for the gaming board to promptly license applicants and otherwise create a regulatory system.

Regardless, the gaming board, which began allowing gambling at a handful of locations this month as a test, says it’s now ready for the games to begin.

“As you probably all know, we are set to go,” gaming board chairman Aaron Jaffe said last week at the board’s monthly meeting. “If you’re ready to go, we’re ready to go.”

But video gambling riches are far from a sure bet.

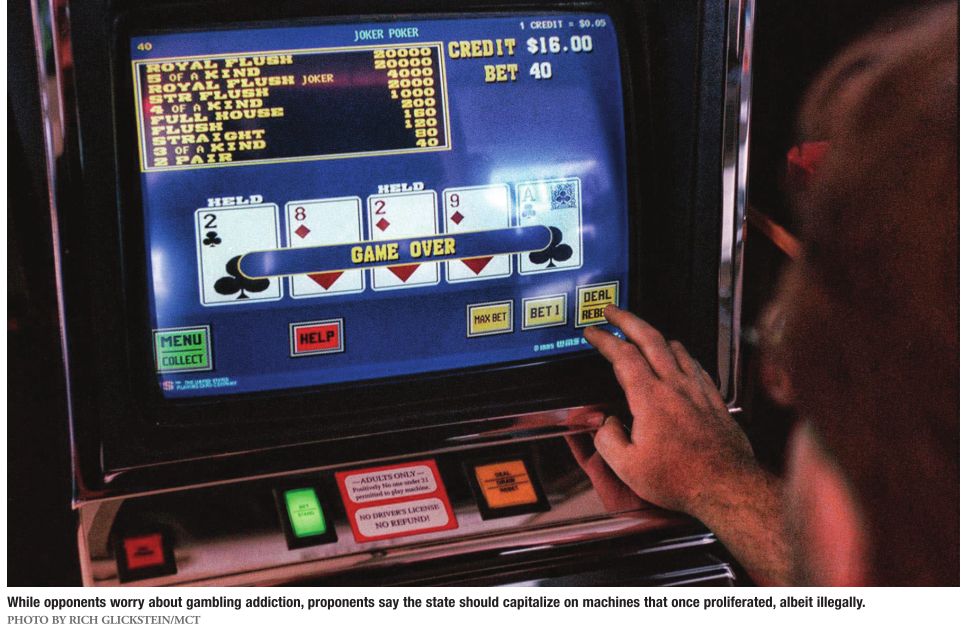

Brauer and other lawmakers who voted in favor of video gambling say they were swayed in part by tens of thousands of illegal machines that were already being played throughout the state without the government collecting a percentage. If it’s already happening, legislators figured, the state should cash in.

Thanks to a five-machine limit per location contained in state law, fewer than 20,000 machines could be installed now if every location that has applied for a license gets one.

That’s far fewer than the estimated number of machines that existed three years ago when lawmakers legalized video gambling.

Furthermore, the law allows local governments to ban video gambling, and hundreds of municipalities and counties have done exactly that. As a result, state forecasters have dramatically reeled back initial projections that showed the state might collect more than a half-billion dollars a year from video gamblers.

Illegal machines disappear

When state lawmakers approved video gam bling, legislators counted on video gamblers to help fund a $31 billion capital budget earmarked for road improvements, repairs to bridges, updates to crumbling buildings and, this being Illinois, a fair number of grants to such favored private organizations as the Irish American Heritage Center in Chicago and VFW posts throughout the state.

Pro-gambling politicians had reason to be confident. Even before lawmakers legalized video gambling in 2009, illegal so-called gray machines had proliferated for years, mostly in bars. The “for amusement only” disclaimers on the devices that gobbled untold riches were, well, amusing, and everyone knew it.

Aside from annual license fees of $30 per machine, the state collected nothing from the devices that looked like electronic slot machines, worked like electronic slot machines, sounded like electronic slot machines and paid off, albeit under the table, like electronic slot machines. By some estimates, more than 20,000 such games were

licensed in 2009 when the General Assembly voted to legalize the

business and take a cut of profits, with the state collecting 25 percent

and local governments getting an additional 5 percent. When unlicensed

devices were considered, estimates ranged as high as 60,000 machines.

No

longer. Check a dozen bars at random in Springfield and you’ll find

more ashtrays, smoking ban notwithstanding, than video poker machines or

any of the other so-called gray machines that once were as ubiquitous

as beer on St. Patrick’s Day.

“They’re

all gone,” says Mike Walton, a board member of American Legion Post 32

who acknowledges that the establishment on Sangamon Avenue was one of

scores in Springfield that once offered video gambling without oversight

from state gaming regulators.

Possession

of so-called gray machines became a felony in mid-August, but numbers

from the state Department of Revenue and the Springfield city clerk’s

office show the decline began three years ago.

The

number of amusement-device licenses issued in Springfield has dropped

from more than 1,000 in 2010 to 815 this year, with those figures also

including jukeboxes, video games such as Golden Tee and other gizmos

that aren’t used for gambling. The state Department of Revenue issued

more than 64,800 amusement-device licenses in 2010 and 62,200 in 2011.

Fewer than 46,000 licenses have been issued for the current licensing

year that began Aug. 1.

Sue

Hofer, spokesman for the state Department of Revenue, says the state is

still issuing licenses for “simulated gaming” devices that are

perfectly legal so long as no jackpots are paid.

“It

is up to the taxpayer to know whether their machines are in compliance

with the new gaming law,” Hofer wrote in an email. “A number of

taxpayers have indicated they have been getting rid of their simulated

gaming machines over the past three years in anticipation of video

gaming going online. This could be a potential cause of the decline in

the number of decals issued.”

Fear

of prosecution prompted bars to get rid of gray machines that paid

jackpots, Walton and others say. But even before possession of such

machines became a felony last month, the gaming board warned that it

would be tough on establishments that have allowed illegal gambling.

“It’s

my personal opinion that if you’re in the gambling racket today

illegally, you shouldn’t be able to operate legally,” chairman Jaffe

said in 2009. “It’s my feeling we should be as strict as we possibly

can.”

Applicants for

video gaming licenses must tell the board whether they have ever

“facilitated, participated or enabled” the use of amusement devices for

gambling. But after the board declared that it would ask applicants

whether they had ever been involved with illegal gambling, the

legislature passed a law in 2010 that defined “facilitated, participated

or enabled” as having been convicted of a felony gambling offense,

allowing applicants to answer “no” on licensing forms so long as they’d

never been prosecuted and found guilty.

Jaffe

has called the 2010 law a “disaster,” saying that lawmakers shouldn’t

take power away from the board. Lawyers familiar with the statute say

that the board can still consider past conduct, so the fate of

applicants who have had gray machines but not been convicted of gambling

offenses isn’t entirely clear.

The

board has revoked at least one license for jumping the gun on

legalization. The revocation came in April, after the board received a

tip that AAA City Vendors Gaming owned by Loyal T. Sprague III was

supplying gray machines to an American Legion post in Bartonville, near

Peoria, that was paying jackpots. It shouldn’t have been a surprise.

In 2004, the Peoria Journal Star reported

that Loyal T. Sprague, Jr., who had recently died from four gunshots to

his belly, had been a heavy gambler whose company, City Vendors

Amusement, supplied games to bars. Police reportedly found $80,000 in

cash in Sprague’s home, the newspaper reported, and those who knew him

said that he held gambling parties at his home and would bet as much as

$10,000 on the flip of a coin. The county sheriff called him “an

interesting dude” who always tried to help people.

The bar game business ran in the family:

Sprague had inherited it from his father, according to the Journal Star report,

and Loyal T. Sprague III, Sprague’s son, was also involved in the

enterprise. In 2010, one year after state lawmakers legalized video

gambling, the son incorporated AAA City Vendors Amusement and got a

license from the state.

When

the board unanimously voted to revoke the company’s license in April,

Jaffe said that regulators do their best when vetting applicants, but

success isn’t guaranteed.

“It’s

also clear to me that illegal activity in this industry does not exist

in a vacuum,” Jaffe said. “The bar owners know this is occurring, the

bartenders know that illegal payments are being handed out, the bar

patrons and gamblers know this is happening and, most distressing of

all, many local law enforcement officials have turned a blind eye to

this crime for decades.”

An

application from the Bartonville American Legion post where AAA City

Vendors Amusement had installed machines is pending at the gaming board.

Opinions vary on whether the state should grant it.

Christopher

Stone, a Springfield lobbyist who is seeking a license for a string of

planned businesses that will feature video gaming, says no. The gaming

board, he said, should be “fair and consistent:” If a supplier of gray

machines isn’t allowed to operate, then the bar where the machines were

paying out shouldn’t be allowed to get a license, either.

“You need two to tango, right?” Stone says.

“If they’re consistent with their policy, the American Legion doesn’t get one.”

A

manager at the Bartonville American Legion post said that the post

hasn’t heard from regulators since submitting a license application

about two months ago. Gaming board officials visited the post last

spring and demanded that gray machines be removed, the manager said.

“Yes,

we are concerned,” said the manager, who requested that his name not be

published for fear of running afoul of regulators. “We’ll just have to

see what happens.”

But

Walton, who works for the Sangamon County sheriff’s office and was once

Springfield’s police chief, said that he’s not worried about the gaming

board rejecting an application from his legion post because the

organization once had gray machines.

“If they did that, probably 90 percent of the applicants wouldn’t get one (a license),” Walton said.

Few licenses granted

So far, the American Legion post on Sangamon Avenue is losing when it comes to legalized video gambling.

Walton

says the post, which has not yet been awarded a license so gambling can

begin, has spent as much as $4,000 on lawyers, licensing fees,

fingerprinting and electricians to wire the building for new machines.

When gambling does start, Walton doesn’t expect to make as much money as

in the past. The gov ernment, he points out, is going to take a 30

percent cut.

The

state, meanwhile, is expecting a much smaller windfall than originally

envisioned. Since the General Assembly legalized video gambling,

forecasters have been reeling back revenue projections that are now a

fraction of what lawmakers were told when they voted to legalize.

In

2009, the state predicted that its cut from video gambling would total

between $288 million and $534 million. The state Commission on

Government Forecasting and Accountability last year slashed that

estimate, predicting that video gambling will raise between $184 million

and $341.2 million a year. The commission recently cut its prediction

even further in a yetunpublished report, saying that video gambling will

raise between $105.6 million and $196.2 million in annual revenues.

Municipalities

and counties can ban video gaming, and COGFA’s forecast has shrunk

because more than 300 communities, including Chicago, have done exactly

that, says Eric Noggle, senior analyst for the commission. More than 63

percent of the state’s population lives in jurisdictions that don’t

allow video gambling, he said.

The

commission’s forecast, based on the state receiving between $70 and $90

from each machine each day, is conservative, Noggle says. While COGFA

has said that predicting revenue from video gambling is “challenging,”

Noggle said he doubts that there will be as many legal machines as there

were illegal ones during unregulated days when bars weren’t bound by a

five-machine-per-location limit now contained in state law.

“We

all know a lot of this has been going on illegally for many years,”

Noggle said. “I’d be surprised if we actually reached the saturation

point of where it was before.”

In

Sangamon County, 84 bars, restaurants and other businesses have applied

for licenses to conduct on-premises video gambling, according to the

most recent figures available from the state gaming board, which has

granted just one license in the county, and not to a usual suspect.

With

hardwood floors, Perrier Jouet champagne and single-malt Scotches

costing more than $150 a bottle, It’s All About Wine on Wabash Avenue in

Jerome isn’t exactly a beerand-a-shot bar, but it is the first business

in the county to win the right to offer video gambling to patrons. Joe

Volenec, co-owner, calls it an experiment. He figures his customers

might enjoy electronic games of chance as they sip high-end chardonnays.

“I’m

not in the gambling business, I’m in the wine business,” Volenec said.

“I don’t see a downside to it. Let’s see what happens.”

The Abraham Lincoln Capital Airport is also hoping to cash in.

“We’ve

kind of had this on our radar screen as an additional revenue stream

for some time,” says airport executive director Mark Hanna. “Looking at

where this is going, it could be a very popular form of entertainment.”

More

than a half-dozen truck stops in Sangamon County have applied for video

gambling licenses. But fears of video poker on every street corner are

not coming true.

Bars and restaurants that pour alcohol are eligible to apply for video

gambling licenses, but fewer than 70 of more than 220 establishments

with licenses to pour alcohol in Springfield have applied. What the

future might hold is anybody’s guess.

Paul

Jenson, a Chicago attorney who represents businesses involved with

video gambling, predicts an uptick in license applications once video

gambling starts in earnest.

“I

think, eventually, these establishments will apply (for licenses),”

Jenson said. “I think, frankly, a lot of them don’t think it’s reality. …

Is the roll-out going to be a little slower than we thought a year or

two ago? Probably.”

Stone,

the Springfield lobbyist, estimated that between 10 and 20 percent of

bars won’t be able to get licenses for reasons ranging from inability to

pass background checks to delinquent taxes. State law also gives the

gaming board the authority to deny a license if it feels that permitting

machines would result in an “undue concentration” of gambling devices

in a geographic area.

But plenty of people, including Stone, see opportunity.

Stone

is the public face of Lucy’s Place, a partnership that plans on opening

video gambling parlors in Springfield and several other cities in

central and downstate Illinois. The company has yet to apply for

gambling licenses in Springfield, where it has liquor licenses for two

yet-unopened locations, but it has applied for 10 licenses in such towns

as Litchfield, Wood River and Columbia.

“I don’t think we’re going to rule out any communities if they decide they would like to do it,” Stone said.

Stone

is aiming for gamblers who appreciate the quietness afforded by

establishments that resemble coffeehouses more than bars or taverns.

Under state law, establishments must prohibit anyone younger than 21

from gambling, and Lucy’s Place will take care of that by barring minors

and checking driver’s licenses when people enter. While cocktails might

eventually be offered, beer and wine will come first. Lottery sales are

planned, as is food service. True couch potatoes can drop by and just

watch television.

It

is the sort of enterprise that worries Anita Bedell, executive director

of Illinois Church Action on Alcohol and Addiction Problems, which has

long opposed all forms of gambling in the state. The disappearance of

video gambling devices since possession of gray machines became a felony

is the proverbial calm before the storm, Bedell says.

“As

soon as it (legal video gambling) starts, it could mushroom,” Bedell

says. “I’ve read reports that said it could go up to 75,000 (machines).

It’s going to increase crime. It’s South Carolina had one machine for

every 100 residents, and the number of Gamblers Anonymous groups grew in

direct proportion.

Proponents

of video gambling say that the law in Illinois that limits the number

of machines per location and doesn’t allow machines in places other than

truck stops, fraternal organizations, veterans groups and businesses

that pour alcohol, was written with an eye toward problems in Iowa and

South Carolina that resulted in bans.

“We’re not throwing it in everywhere,” says going to increase addiction. … Does Springfield really want to become

another Las Vegas?” Bedell points to South Carolina and Iowa, which both

banned video gambling outside casinos after forays into legalization.

“I think it’s something that goes on today that

has gone on forever, and so I think it’s really silly for these

establishments to be operating illegally when they actually want to

operate legally, which increases revenue to the state.”

Just four years

after allowing video gambling, Iowa lawmakers in 2006 banned machines

that had been installed by the thousands in grocery stores, gas stations

and other businesses frequented by kids. After 14 years of legal video

gambling, South Carolina banned video poker in 2000. The machines had

become ubiquitous – by some estimates Rich Mitchell, director of the

Illinois Coin Machine Operators Association, which lobbied more than two

decades for legalization.

And

gambling in Illinois is hardly new. “People have been gaming in this

state for the last 80 years illegally,” Stone says. “You can’t regulate

and mandate choice. To legalize and to regulate it, that’s a good thing.

To actually have transparency on this is a great thing.”

State

needs revenue Mitchell says his group wants video gambling to start as

soon as possible, but he believes that the gaming board is doing the

best it can.

“They’ve

just absolutely got their hands full,” Mitchell said. “Member operators

have their hands full. I would say the roll-out is going to take three

years to complete.”

O’Shea,

the gaming board spokesman, said part of the delay is due to would-be

licensees not filling out paperwork properly. The board conducts

background checks on every applicant, and multiple ownership of entities

seeking licenses can complicate the process, he said.

“A

lot of the applications we’re getting are incomplete,” O’Shea said.

“Our licensing analysts have to go back to the locations and straighten

things out. It’s proven to be time consuming.”

Rep.

Brauer predicts that there will eventually be the same amount of video

gambling as there was in the days of gray machines. He said he would

prefer that video gambling not exist, but that’s not realistic.

“I

think it’s something that goes on today that has gone on forever, and

so I think it’s really silly for these establishments to be operating

illegally when they actually want to operate legally, which increases

revenue to the state,” Brauer said.

Sen.

Larry Bomke, R-Springfield, who also voted for legalization, said that a

progambling vote is a tough one in the Springfield area, which has a

conservative bent. Like Brauer, Bomke said that his support was

pragmatic.

“The state

needs the revenue,” Bomke said. “It just seemed to me that they’re

(machines are) already there. We ought to be taking advantage of them.”

Bomke

said he’s heard from fraternal organizations concerned that they will

not make as much money as in the past due to the five-machine limit. He

said he’s upset with municipalities that have enacted video gambling

bans even while standing to benefit from public-works projects funded in

part by gambling proceeds. And he expected the state to reap financial

rewards far sooner than it has.

“The anticipation was, it would be up and running within a year,” Bomke said. “Obviously, that has not occurred.”

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].