New historical marker commemorates the heritage of a proud community

HISTORY | William Furry

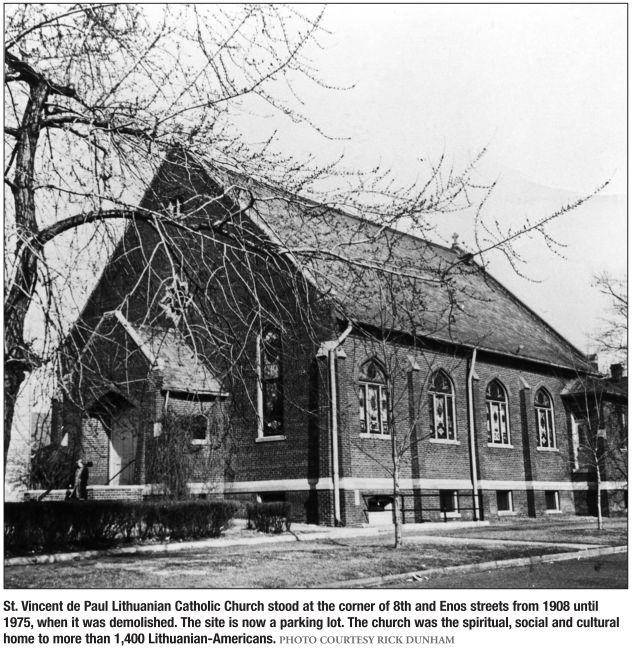

The placing of a church cornerstone is an act of faith. For the founders of Springfield’s St. Vincent de Paul Lithuanian Catholic Church it was an act of survival. Exiled from their tiny homeland on the Baltic Sea, they came to America at the turn of the last century seeking peace, opportunity and religious freedom on the city’s north side. The cornerstone for St. Vincent’s was set on March 4, 1908, and Springfield’s Lithuanian-American community thrived for the next 60 years.

Time and church politics eventually caught up with the peculiar parish. The doors to St. Vincent de Paul’s, the last national church in the Diocese of Springfield in Illinois, closed on New Year’s Day in 1972, a victim of the Second Vatican Council and diocese directives compelling ethnic churches to “assimilate” into English-speaking parishes. But Springfield’s Lithuanian-American community had come too far to see their heritage dissolve without a struggle. They wrote letters to the bishop. They signed petitions. They looked for political allies around the state. And they took their protests to the media.

Still the bulldozers came and their beautiful north-side church, the foundation of which parishioners’ fathers and grandfathers had dug by hand, became a parking lot. The Lithuanians of Springfield were “invited” to assimilate into the English-speaking church community, or part ways with the diocese. The death in 1975 of Father Stanislaus O. Yunker, parish priest at St. Vincent for 47 years, spelled the end of any hope to revive the parish. But the community of Springfield Lithuanians did not die. True to their resilient national roots, they quietly waited for an opportunity to burst into bloom again.

Historical marker dedicated

Such an occasion was Saturday, May 19, 2012, when the Lithuanian Club of Central Illinois and the Illinois State Historical Society (ISHS) gathered in Enos Park on Springfield’s north side to unveil and dedicate a new historical marker, “Lithuanians in Springfield.” More than 120 friends, parishioners, and guests assembled in the park for the dedication ceremony, which included speeches by public officials, singing of the Lithuanian and American national anthems, and a memorial tribute to the elders of the community who had passed away.

Sandy Baksys, a second-generation Lithuanian-American born and raised in Springfield and a member of the Lithuanian- American Club of Central Illinois, was the catalyst for the program.

“I wanted a marker in the historic Enos Park neighborhood, a site that was visible and protected, a location that could be identified historically with the Lithuanian community in Springfield,” Baksys told Illinois Times. To that end she canvassed the neighborhood, worked with the Springfield Park District and the Enos Park Neighborhood Improvement Association, and raised more than $3,000 in donations from club members and friends.

Among the speakers at the dedication that morning were U.S. Congressman John Shimkus (District 19, Carlinville), a Lithuanian-American; Springfield mayor Mike Houston, who once lived in the historic neighborhood and attended St. Vincent de Paul Church; Leslie Sgro, president of the Springfield Park District; and Stu Fliege, chair of the ISHS Historical Markers Program. Kourtney Baker, a fourth-generation Lithuanian-American whose family was among the first to arrive in Springfield, dressed in traditional Lithuanian clothing and passed out memorial flowers. Her mother, Donna Baker, read a letter from U.S. Senator Richard J. Durbin, a second-generation Lithuanian- American from Springfield who serves as the Assistant Majority Leader (Majority Whip) in the U.S. Senate, and on the Senate Foreign Relations and Judiciary committees.

“The history of Illinois has been rich with the presence of Lithuanian-Americans and their contributions as citizens of the state have been monumental,” wrote Sen. Durbin. “Lithuanian- Americans sought to forge a place for themselves in the world despite language barriers, lack of formal education, and the hardships of the labor that was offered them. The tenacity of these hard-working, risk-taking individuals is exemplary of ideal citizenship and has helped propel our entire society into the future.”

In his remarks, Congressman Shimkus noted that more than 700,000 people of Lithuanian descent live in the U.S., including a large contingent in Illinois. At one time in Chicago there were more than a dozen Lithuanian parishes, and more than 13,000 Lithuanian- Americans are interred at the Lithuanian National Cemetery in Justice, Ill. Springfield, by contrast, had just one parish, but its roots are deep in history.

Lithuanian roots

Situated in northeastern Europe on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, Lithuania is bordered by Poland, Latvia, Belarus and a Russian exclave to the southwest. It has a population of 3.2 million living in a territory roughly the size of West Virginia. For more than 200 years (1569-1772), Lithuania and Poland were part of a loose commonwealth, but Lithuania’s geography made it ripe for trespass. Napoleon marched through Lithuania on his way to Russia in 1812, a scenario that would be repeated by Russians and Germans over the next century and a half.

“Most of the first Lithuanian immigrants who came to Sangamon County around the turn of the last century were poor farmers who found work in the coal mines,” says Baksys. “The Russian Empire, which had conquered Lithuania in 1795, banned the Lithuanian language, repressed the Catholic Church, and conscripted young men into the Tsar’s army for 25 years at a time, when the average lifespan was 45 or 50. America offered jobs, opportunity, freedom and a future.” Some Lithuanian exiles found work first in Scotland, later coming to Illinois via the Pennsylvania coalfields.

Springfield’s Lithuanian population didn’t settle in one part of town. When the faithful laid the cornerstone for St. Vincent in 1908, the new church was within walking distance of area coal mines and factories, including the Springfield Watch Company, Pillsbury Mills, the International Shoe Company and other north-side businesses.

Springfield mayor Mike Houston’s father worked at the International Shoe Company, and his family lived for a time on North Eighth Street. Houston and his mother attended St. Vincent’s regularly in the 1950s. “I remember the congregation was older, and there were many Lithuanian ladies dressed in black with head coverings,” he said. ”It was a small but beautiful

sanctuary,” Houston recalls, “with part of the service in Lithuanian

and part in English. Father Yunker, because of his heavy accent, was

sometimes difficult to understand, but he was known for saying the

fastest mass in town.”

Helen

Sitki Rackauskas, a second-generation Lithuanian-American and former

St. Vincent’s parishioner, was married at St. Vincent’s, as were her

parents. She said that her Lithuanianborn father was a coal miner who

worked at the Peabody “Capitol” Mine at 1900 East Adams St. Rackauskas,

now in her 80s, still has his lunch bucket and fondly recalls how when

she was a child in the 1930s her father would send her down to the local

tavern “to fetch him a bucket of beer after work. I still remember – it

cost 15 cents,” she said.

Most

of the women in the community took in boarders to make ends meet,

Rackauskas said. “Mom always had about three boarders, and they were

usually miners. She cooked all their meals, did their laundry, and kept a

galvanized tub filled with hot water for them to bathe. She would even

scrub the coal dust off their backs when they came home from the mines.”

Mary

Urbanckas’s father also worked in the Springfield mines and her mother

kept boarders. Urbanckas, 95, remembers learning to read and write

Lithuanian in the basement of St. Vincent during the summer months,

writing letters to relatives for her mother “back in the old country.”

During the Depression, she said, her family, like most, kept a garden.

“Mother canned everything because there was no money. We’d kill a pig,

and it would last us all summer.” The garden nourished them, but the

church sustained them. It was always at the heart of the community,

Urbanckas said. Like her parents, Urbanckas was married at St. Vincent,

and one of her grandchildren was the last christened in the church.

A penchant for gadgets

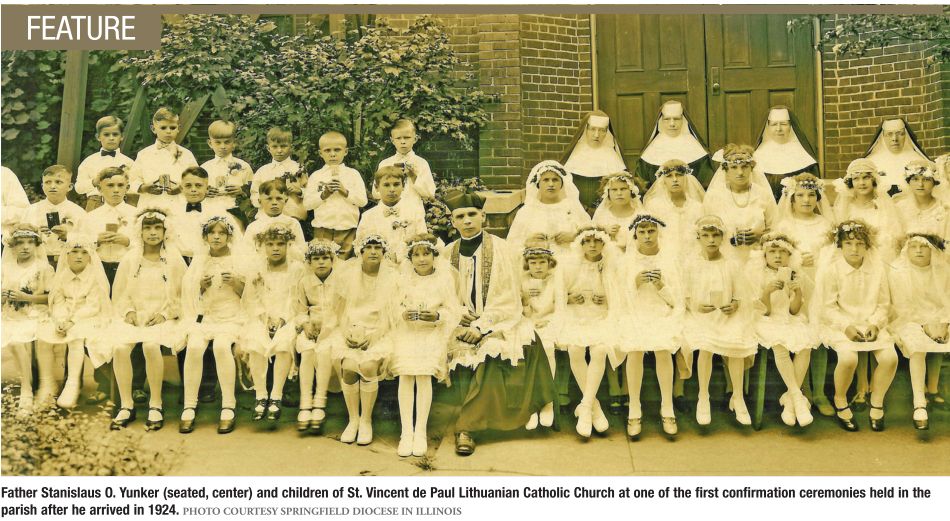

Father

Yunker was St. Vincent’s fourth parish priest. Born in Lithuania and

educated in Germany, his family settled in Quincy during the war years.

Ordained in 1923, he arrived to pastor the flock at St. Vincent in

Springfield on Dec. 1, 1924, and never left.

“Father

Yunker liked gadgets,” said Joseph Turasky of Springfield, who served

as an altar boy at St. Vincent during the 1950s. “He had a short-wave

radio and at night he’d talk to people around the world. Once we heard

him speaking – people all over the neighborhood – through our television

sets. When we asked him about it the next day, his comment was, ‘How

was the reception?’” St. Vincent’s priest also had a thing for fast

cars, boats, slot machines, telescopes and allthings electronic. “He

could control all the lights and heat in the church and sacristy by

remote control from the rectory,” Turasky said. “He also kept a

motorboat at Lake Springfield – one of the biggest on the lake.”

Others

remember Father Yunker for his many kindnesses. Louise Sitki tells the

story of how she eloped to Mississippi with Helen Rackauskas’s brother,

Raymond. “It was on a Friday night in May 1957,” she said. “After the

civil ceremony on Saturday, we drove straight back to Springfield. On

Sunday – Mother’s Day – we told Father Yunker what we had done. He

didn’t holler at us – or anything. Instead, he held a special mass and

married us in the church the following Wednesday. And he didn’t charge

us a dime,” Sisti remembered. “You sure couldn’t do that today!” Ann

Pavemetski Traeger sang in St. Vincent’s choir, considered to be one of

the finest in the city. “During the holy days Father Yunker would have

the choir over to the rectory after church for snacks and refreshments,”

she recalled. She remembered how, during Advent, Father Yunker and the

trustees of the church would make rounds through the parish, blessing

homes and collecting the annual tithe. Parishioners would clean their

homes until they shined, and Father Yunker would leave packets of

non-consecrated “host” (“Kucios”) for the families to share at their

Christmas Eve meal. “If you couldn’t afford to tithe,” Traeger recalled,

“Father Yunker said not to worry. And he would bring a big black bag of

candy to share with the children.”

At its peak, St. Vincent numbered around 1,400 parishioners. During the mine closings of the 1920s and ’30s, many

Lithuanian- Americans lost their jobs and left town. World War II also

took a toll. But St. Vincent held onto the faithful, and the parish

celebrated its Golden Jubilee in 1956.

The second wave

The second wave

After

1948, a second wave of Lithuanian immigration brought new families, new

hope and new zeal into the community, solidified by Cold War politics

and the Soviet occupation of the Baltics. This wave was mainly of

professionals – doctors, engineers, attorneys and educators –

Lithuanians who found themselves on the wrong side of the Iron Curtain

and in danger of exile, prison or worse under Soviet rule.

Springfield’s

Mike Lelys, superintendent of Oak Ridge Cemetery, was born in 1948 in a

displaced persons camp in Austria after his family fled Lithuania. They

arrived in New York in 1950.

His

father, Constantine “Connie” Lelys, spoke seven languages, played the

violin and accordion, and had exquisite penmanship, but his first job in

Springfield was as a janitor at St. Patrick Church and School on South

Grand. “I remember my dad riding his bicycle across town to shovel coal

at 4 a.m. to stoke the furnaces at the church, just to make a better

life in this country for me.” Lelys’ father eventually found work with

the Illinois Highway Department and later at the state Department of

Natural Resources, where his skill as a draftsman was valued highly.

“What

impressed me most about my father was his work ethic and personal

sacrifice,” said Lelys. “He came from a different culture with a

different set of skills, yet he became successful by American standards,

sometimes working two jobs to get by. The endurance and sacrifice of

these early immigrants – not just Lithuanians – was extraordinary. Today

I am much more aware and have a better cultural understanding of

nations that were suppressed by communism.”

Benius

“Ben” Zemaitis was born in Lithuania in 1933, a teenager at the end of

WWII. Although his father was an attorney and his mother a dentist,

neither could find employment in Soviet-occupied Lithuania after the

war. “The Soviets were suspicious of all educated Lithuanians and

considered them dangerous,” Zemaitis said. His parents escaped to

Wurzburg, Germany, and sought refuge under the “Displaced Persons (DP)

Act of 1948,” a U.S. immigration law that offered qualified “DPs”

opportunities to emigrate to America.

Zemaitis

and his parents were lucky. “We stayed in a former Franciscan Convent

where 75 percent of the people were Lithuanian,” Zemaitis recalled of

his time in the DP camp in Germany. “I attended a Lutheran high school,

served as an altar boy, and learned English from the U.S. servicemen.”

His relatives didn’t fare so well. Those who stayed behind were sent to

Siberia. Others simply “disappeared.”

The

Zemaitis family resettled in Marquette Park on Chicago’s south side.

Ben graduated from high school and attended the University of Illinois

at Chicago and later Urbana- Champaign, earning a degree in business

management. He took a state job at the Illinois Department of Revenue, a

position that led to a move to Springfield in 1971. He retired from the

state in 1999 as a certified professional auditor.

Lithuanians in Springfield

Following is the text on the new Illinois State Historical Society marker at Seventh and Enterprise in Enos Park.

Following is the text on the new Illinois State Historical Society marker at Seventh and Enterprise in Enos Park.

Lithuanians

arrived en masse during Sangamon County’s coal boom. Numbering several

thousand with their families by 1920, they fled political and religious

repression, conscription, poverty and a total ban on their language in

the Czarist Russian Empire. In 1908, at Eighth and Enos streets, they

built their “national” Catholic church, St. Vincent de Paul’s, which for

63 years was a focus of Lithuanian language and identity. In 1917, the

church was called the most important “melting pot” in the city with

1,200 Sunday worshipers. Immigration restrictions, coal mine closures

and assimilation all took their toll on local European ethnic groups

after 1920. However, the significance of St. Vincent de Paul’s only grew

when Lithuania was annexed by the Soviet Union in 1940 following 22

years of independence. With freedom in the homeland again extinguished,

Lithuanian identity abroad assumed a moral imperative. National feeling

also was reinforced by a local influx of World War II refugees under the

U.S. Displaced Persons Act of 1948. And it persisted decades after St.

Vincent’s became Springfield’s last “national” church to close in 1971.

In 1988, a daring “Singing Revolution” in Lithuania (1987- 91) inspired

439 local Lithuanian- Americans to form a new club to celebrate their

heritage. Lithuania was restored to independence with the breakup of the

Soviet Union in 1991.

His

move to Springfield coincided with the closing of St. Vincent de Paul.

“I never attended church there so I didn’t know how many Lithuanians

lived here,” he said. His contribution to the local Lithuanian-American

community came later and, oddly, on a visit to Lithuanian in 1999. There

he became reacquainted with then-Lithuanian President Valdas Adamkus, a

Lithuanian-American friend

from his UIC days. Adamkus had worked in Chicago for the Environmental

Protection Agency, Midwest Region, from 1970 to 1997. He moved back to

Lithuania in 1997 and was elected president. Adamkus invited Zemaitis to

work as a consultant with the Lithuanian comptroller general. Working

pro bono, Zemaitis organized a three-week training course for government

auditors, and for his efforts he earned a medal and the gratitude of a

nation.

As a founder and current

director of the Lithuanian-American Club of Central Illinois, Zemaitis

provides a direct cultural link to the homeland. Following the death of

his first wife, Vita, Zemaitis married his second wife, Grazina, one of

Sangamon County’s newest Lithuanian immigrants. In their Chatham home,

Lithuanian is the first language.

The candle flickers

Mike

Lelys was married at St. Vincent Church in 1971, one of the last

weddings there before it closed. He remembers how the men gathered

outside the church doors before Sundaymorning mass and talked about

everything – politics, work, Lithuania, baseball – “it was really the

social gathering place for the Lithuanian community in Springfield,” he

said. When the doors closed and the church came down, he said, it was as

if the diocese had abandoned them.

Some

St. Vincent parishioners reluctantly found new church homes in the

growing Springfield suburbs. Others simply stopped attending mass. For a

while the diocese brought in Lithuanian priests to hear confession at

other churches. After a while this too stopped. For some families, the

candle was extinguished, never to be lit again.

Fast

forward to 1988, during the collapse of the Soviet Union, when a newly

formed Lithuanian-American Club in Springfield rallied around the push

for Lithuanian independence. Some members began a letter-writing

campaign to affirm the U.S.’s 1922 formal recognition of Lithuania as a

free and independent nation. Lithuanian-Americans, energized by the fall

of the Berlin Wall and the Soviet regime, found reason to sing when

their homeland regained its independence in 1991.

Tom

Mack was the first president of the Lithuanian-American Club. His

father, Johnny Macarauskas – shortened to “Mack” by his coal-miner

friends – came to Springfield from Lithuania in 1920 with his mother and

brother. His father was already here working in the mines.

Johnny Mack, too, worked in the mines, then opened a butcher shop and

grocery near Pillsbury Mill, later earning a place in Springfield’s

fast-food history by owning the city’s first two McDonald’s franchises.

Tom

Mack served for 10 years as president of the Lithuanian-American Club,

stepping down after a minor stroke. “At its peak the club was around 440

members,” Mack says. Most of the original members were newer “DPs” and

second-generation descendants of the first immigrants. The third

generation, he says, has become more assimilated into American culture

and has only a distant memory of going to grandma’s for a traditional

meal. “Most kids today are more interested in their iPods than in their

ethnic heritage,” he observed.

Not

all kids. Fourteen-year-old Kourtney Baker dreams of being a farmer

like her Lithuanian-American grandparents, who lived near Pleasant

Plains. She’s raising six chickens in her backyard, each with a

Lithuanian name. After Kourtney graduates from high school, she plans to

visit Lithuania with her mom.

Despite

diminishing numbers, Springfield’s Lithuanian community finds

opportunities to celebrate its unique identity. The Lithuanian- American

Club (about 70 members) publishes a quarterly newsletter, edited by

Kourtney Baker, that promotes community events and keeps members

informed of milestones and special projects.

Sandy

Baksys and her friend Melinda McDonald are attempting to build a

virtual community with a “Lithuanians in Springfield” blogsite devoted

to local Lithuanian-American family histories. They encourage families

to share stories and digital photos online. (Find out more about the

blog at www.lithSpringfield.com.)

The

Springfield Diocese in Illinois also looks for ways to reconnect with

St. Vincent’s lost parishioners. Diocese archivist Michele Levandoski

says the story of Springfield’s Lithuanian national church is part of

the community’s larger history and needs to be preserved before the

generation that remembers it best is gone. She invites members of the

old parish to make an appointment and come visit her at the Diocese’s

Pastoral Care Center.

According

to Baksys, the “Lithuanians in Springfield” historical marker sparked

renewed interest in the club and unlocked doors that had been closed for

decades. At the marker dedication, ISHS director Stu Fliege presented

Baksys with three reeds salvaged from the church’s pipe organ. A man in

the crowd revealed he had preserved the church’s cornerstone. And

several large, handpainted murals once displayed in the sanctuary have

also been recovered, 40 years after the church was demolished.

For

some, the Lithuanian-American story in Springfield came to an end with

the closing of St. Vincent de Paul Church on that cold January day in

1972. For others, the adventure is just beginning. One thing is for

certain. The stories of Springfield immigrants – those of the past

century and of the present day – have much to teach us, not only about

the human spirit, but about the ever-changing world and our place in it.

William Furry, former Illinois Times editor, is executive director of the Illinois State Historical Society and a sixth generation Springfieldian.