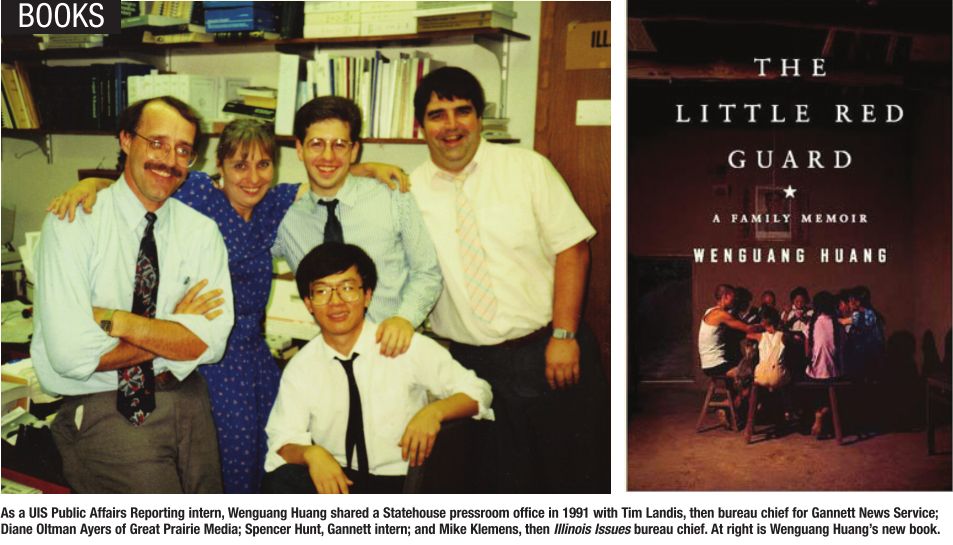

UIS commencement speaker and former student portrays life in The Little Red Guard

BOOK REVIEW | Mary Bohlen

I thought I knew the story

of Wenguang Huang, who will be the commencement speaker at the

University of Illinois Springfield May 12. After all, I’ve known Wen for

21 years, first as my student at UIS and later as a dear family friend.

He met my extended family, picked apples in my husband’s orchard and

even flew from Chicago to Boston for my son’s wedding.

I thought I knew the story

of Wenguang Huang, who will be the commencement speaker at the

University of Illinois Springfield May 12. After all, I’ve known Wen for

21 years, first as my student at UIS and later as a dear family friend.

He met my extended family, picked apples in my husband’s orchard and

even flew from Chicago to Boston for my son’s wedding.

I

was wrong. Sure, I knew he had grown up in China during the Cultural

Revolution, was involved in student protests at the time of Tiananmen

and had embraced democracy after a short time in the United States. Not

until I read his just-published and captivating memoir did I realize the

extent of his journey.

Most of all, I did not know he had been the keeper of his grandmother’s coffin, a fact that stands at the center of The Little Red Guard.

In

the book, Wen details his life in Maoist China and his family’s

conflict over clinging to the old Confucian ways or embracing communism.

Nothing represents this divide more than his grandmother’s wish to be

buried in her home village and the government’s mandate for cremation,

her worst fear. Wen’s father risks his standing in the party, the

family’s finances and his wife’s anger to honor, as a filial son, his

mother’s demand he have a coffin ready for her eventual departure.

Caught in the middle is the

young Wen, who dutifully spouts the communist doctrine at school but

sleeps next to his grandmother’s secret coffin for years. Outwardly he

is on the path to party membership. At home he is the favored first

grandson and loyally laps up his grandmother’s love.

“As

a ‘Little Red Guard,’ I was supposed to defend and fight for Chairman

Mao’s revolution, not to guard Grandma’s coffin,” he writes. “Each time I

looked at the Little Red Guard scarf around my neck, I felt a pang of

guilt. I was even hit with a fleeting thought of reporting it to my

teacher. Then, the idea of seeing Father being paraded publicly deterred

me. Besides, Grandma would die of a broken heart and nobody would take

care of me.”

Increasingly

this contradiction, what he calls “a fusion of ideologies and faiths,”

causes him to question his beliefs. So do others as China experiences

the death of Mao, disenchantment with other party leaders, student

protests and eventually economic changes. Wen comes to view China in a

new light when his superior academic standing sends him to study in

Shanghai, in Great Britain and eventually in Springfield, Ill.

Despite

distancing himself from his homeland, Wen can’t shake free of his home.

After years of suppressing the tension among his father, mother and

grandmother, symbolized by the empty coffin in the room, Wen allows his

memories to break free in this coming-ofawareness memoir. It reads like a

novel as he journeys through the changes in his country and himself.

He

paints vivid portraits of his mother coping with three generations in a

two-room house, his father’s loyalty to hard work and communist ideals

and his grandmother’s tiny bound feet. His three siblings get little

attention until late in the book, but then this is Wenguang Huang’s

story. His story is one I am now, and others soon will be, happy to

know.

Mary Bohlen

taught thousands of students, including Wenguang Huang, at SSU/UIS

before retiring in August. She is now a freelance writer and editor.