The longest war

continued from page 15

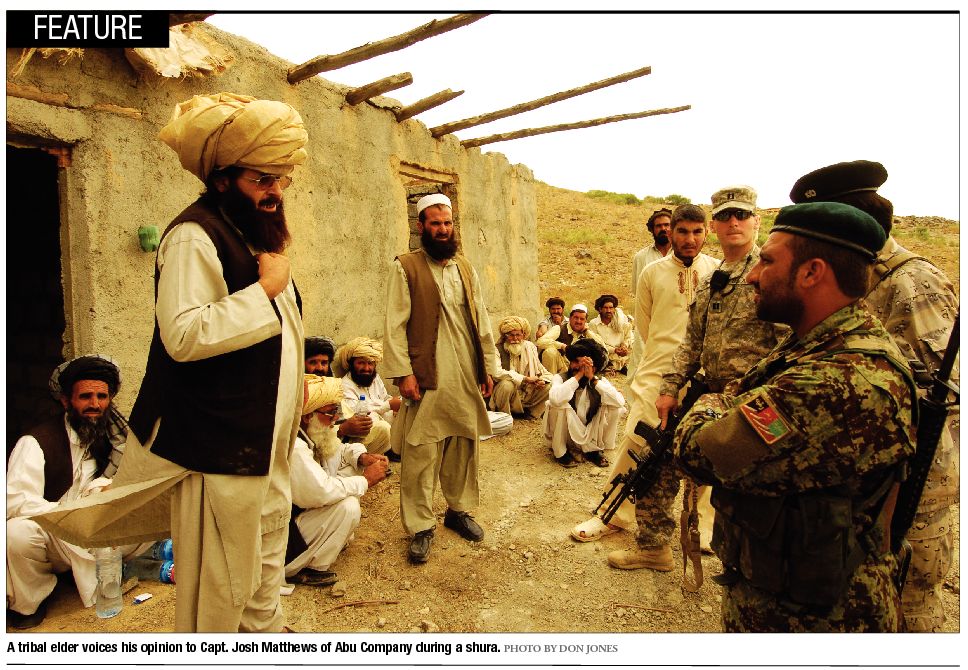

Beyond the geography and troop shortages, Abu Company’s mission is greatly complicated by tribal politics. Most of the smuggling routes in the region are controlled by the powerful Haqqani tribe. Through the generations, tribal groups like the Haqqanis have alternately fought and collaborated with the foreign powers and central governments that tried to control them. Clan and trade alliances go back centuries. When legitimate trade didn’t bring in enough money, the clans turned to smuggling and drug running.

Watson, who as an enlisted man fought in the “Black Hawk Down” rescue in Somalia, was no novice to combat action. And as in Mogadishu, he was used to fighting with a unit that was not at full strength and on the enemy’s home turf.

A key part of fighting under those conditions is artillery and air support. And for Abu Company at Boris and Margah, artillery meant Stephen Peacock, whose gun crews operated 155mm howitzers from Boris.

“Smoke” Peacock joined the Army right out of Portland’s Fort Campbell High School in 1985. He initially enlisted in the National Guard and then joined the regular Army in 1987.

The Army sent him to Fort Sill, Okla., for basic training, and he stayed for artillery school. He initially trained on 105mm howitzers but would eventually be proficient in all the gun systems in the Army. Three deployments in 12 years – two in Iraq and one in

Kosovo – would eventually cost him his marriage. He was divorced in 2005. Now he’s married to Lisa, who works helping families of soldiers, both those stationed in the U.S. and deployed overseas. Peacock’s son, Brian, turned 18 in May and has followed his dad into the Army and the artillery. The sergeant hopes that they’ll get to serve together someday.

Peacock didn’t get his nickname from his chain-smoking habit. It’s the traditional nickname for platoon battery sergeants, dating back to the Civil War, when battery commanders had to walk in front of the guns, clear of their smoke, to observe shell impacts.

Troop strength problems affect Peacock and his gun crews as well. With the end of the hated “stop loss” orders that forced soldiers to keep serving beyond the end of their enlistments, the Army forgot to subtract departing soldiers when they figured his unit’s needs. Before leaving for Afghanistan, he got to train his new gun crews for only two weeks. Weathered and tan, he demands perfection from his soldiers and is merciless in his criticism of them. In Afghanistan, lives depend on them getting it right every single time.

Gus Griechen had already signed up for classes at the University of Alaska when he changed his mind and joined the Army, headed for the infantry. His dad was very proud, Griechen said, but his mom was sad and worried. So he relented and told her he would become a medic instead. She died from cancer on his birthday in 2009, six months before he deployed to Afghanistan – never realizing, he suspects, that a combat medic’s job puts him in the thick of any fighting.

In the two Apaches that provided crucial air support on the mountain that day in June, both gunners were women – two of four

women in the Apache squadron, based about 30 minutes’ flight time from Boris. All four take turns with their crewmates at piloting and operating the 30mm cannons. And while the women in the unit are particularly known for their deadly gun skills, they take exception, not surprisingly, to being picked out for their gender. In one way, though, their gender does matter: They give out minimal personal information because they’ve been told that their gender would cause them to be targeted by the insurgents. Of the two gunners that day, one was a short, slim brunette; the other a tall, blonde, snuff-dipping single mom. The two shared another characteristic: When they talked about their work in the Apaches, they talked with the passion of those dedicated to jobs they love.

Josh Sommers, a rifleman on his first deployment, loves rap and hip-hop music and has no use for ignorant people. According to friends, he has “mad skills” at the Diablo and World of Warcraft computer games.

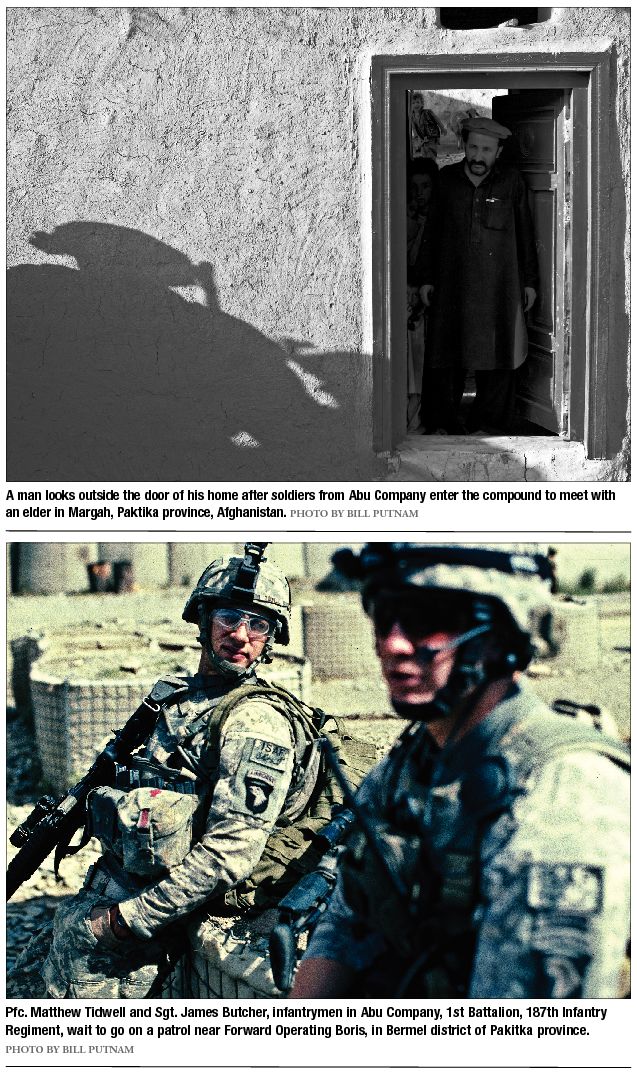

When 2nd Platoon arrived at Margah from Boris, they got a too-warm welcome. A mortar exploded about 400 meters away while the two huge Chinooks were still unloading the troops. As the troops ran for cover and the birds lifted off, another round hit where the helicopters had just been, destroying some equipment.

On this trip, 2nd Platoon would just stay overnight, using Margah as a jumping-off point for their mission. Whichever platoon was there on 30-day rotation patrolled day and night and pulled guard-duty shifts with boredom broken by frequent rocket attacks.

At least the accommodations were luxurious. Margah is a stone-walled compound about 600 yards long and half that wide, with watchtowers at each corner, manned by the Afghan National Army or

Afghan Border Police. Inside are three buildings: a living and

operational space for the Americans, a vehicle storage building with

heavy weapons emplacements on the roof, and a third with barracks for

the Afghan military. “Primitive” and “austere” don’t come close to

describing the conditions.

Chow

is almost exclusively MREs (meal ready to eat), with the occasional

feast of steaks – which quickly become the best steaks ever eaten. There

is no heat or air conditioning, no telephone or Internet connections.

Inside, the bare concrete walls are crowded with cots where the soldiers

sleep in shifts, if they can sleep at all. Every square foot of floor

space is covered with personal items and weapons. Ammunition is stacked

in the halls, and the operations center is full of communication and

video gear. There’s plenty of free time, and the soldiers use it to

sleep, listen to music, play computer games, and work out in the gym.

There

is a very distinctive odor to the combat outpost and everyone in it.

Many of the soldiers don’t shave every day, get haircuts, or change

their uniforms. The “facilities” are two Portacans; the output is

collected in bags and burned. Showers are ice cold – if the tanks have

been filled. Many soldiers warm water in bottles out in the sun, if they

take a shower at all, and most don’t. By the time the soldiers finish

their rotation there, they look a bit like well-armed homeless people.

On

its second morning, 2nd Platoon struck out for Hill 2600, near a

mountain called Patrón (like the tequila – the American military has

named local mountains for liquors and local roads for vehicles). Their

mission was to lie in ambush on a site from which the enemy has often

launched rocket attacks. The Americans have shot so much artillery at

the site that the ground is covered in the steel fragments of shells.

Tripod holes in the ground showed where insurgents had set up their

rocket launcher, time and time again. This time, if the enemy walked

into the “kill box,” the platoon would destroy them.

It

was an exhausting climb, but the first few hours were uneventful. Then

around 3 p.m., the platoon began to take mortar fire. The first round

hit far away, but the enemy gunner made a fast adjustment, and the next

two rounds exploded within 100 meters of the troops. This was not part

of the plan.

Jarmuz

immediately called for artillery support from Boris and air cover from

the Apache gunships. When the helicopters arrived overhead, the

insurgents tried to shoot them down with a heavy machine gun.

The

Apaches fought for almost three hours, making runs to OE to refuel and

rearm. The day ended with a spectacular air strike. The 2,000-pound bomb

stopped the fight long enough for the platoon to continue up the

mountain another 500 meters, where they settled in for the night. While

there was no longer much chance to plan an ambush, their presence would

certainly draw the insurgents into a fight.

The

next morning, Jarmuz had spread his platoon across a north-south

ridgeline, facing east. Pakistan was less than two kilometers away, and

chatter from enemy radios made the unit uneasy.

Besides

the basic fighters, the platoon included Pfc. Griechen, the battlefield

medic; Sgt. Erik Butler a forward observer responsible for calling in

artillery; and a soldier wielding the 60mm mortar. Sixty yards behind

them, two Air Force specialists were there to call in air strikes, along

with two men from Army intelligence and an interpreter.

As

soon as the sun came up, Butler called in information to pinpoint the

most likely avenues from which the enemy might attack – it would make

artillery strikes faster and more accurate.

Around

2:30 p.m., all hell broke loose. The platoon started taking

rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) fire from the northeast and rifle fire

from the east and southeast. The firing was intense, and mortars began

to fall nearby.

A

single grenade hit a tree at the platoon’s command position, nicking

Jarmuz in the neck and damaging Butler’s eardrum. But it did the most

damage to Sommers, who’d been closest to the impact. A fragment

penetrated his helmet and skull, laying open his brain. He was also

bleeding heavily from neck and thigh wounds. The whole platoon began to

return fire. Roberson started doing what he could for Sommers, and the

call went out for “Doc.”

Butler,

at Jarmuz’ order, immediately called FOB Boris, asking for its

long-range artillery to lay down suppressing fire. But the platoon knew

it could take as long as 30 minutes to get that started – a lifetime in

battlefield terms. Not because Peacock and his gun crews were slow, but because of the peculiar rules of engagement that the Americans fight under in Afghanistan.

continued on page 16