That trend continued as news broke of the spring break incident. Williams, then head of the IAC, says administrators only kept him apprised of the subsequent personnel shifts. He learned of all the other details through the daily newspaper.

Discontent with the administration grew louder and a closed faculty meeting in April 2009 resulted in an overwhelming vote of no confidence in Ringeisen and athletic director Rodger Jehlicka. According to the student newspaper, The Journal, faculty members found that Ringeisen and Jehlicka had neither the will nor the competence to make necessary changes within and around the athletics department to ensure it plays an appropriate role within the educational institution. The resolution also raised the issue of whether an individual department could reliably evaluate its own actions without oversight from a more detached body, such as the IAC.

Days later, the campus senate approved a resolution creating Hayler’s investigative committee. In the resolution, faculty stated that Ringeisen had “engaged in a lengthy pattern of unilateral actions in aggrandizing the role of intercollegiate athletics at UIS without consulting the various stakeholders in the UIS community.”

Despite UIS’ continued silence, the nearly two-year-old spring break scandal reemerged this month in the State Journal-Register as it reported on a $200,000 settlement to students for alleged sexual assault by a softball coach. The university’s secrecy over the softball coaches’ resignations caused the school to become the first entity subpoenaed by the attorney general under a one-year-old Freedom of Information Act law.

UIS junior Kelli Kubal, a goalie on the women’s soccer team and a student member of the IAC, agrees with the administration that keeping details of the spring break incident to a minimum was the best route. But she adds that the disagreement between faculty and administrators over who should know what only contributed to the athletic program’s sense of isolation from the rest of campus – something student-athletes are trying to overcome. “The two groups are miscommunicating or not communicating at all, and it feels like it’s the athletes who bear the burden of it.”

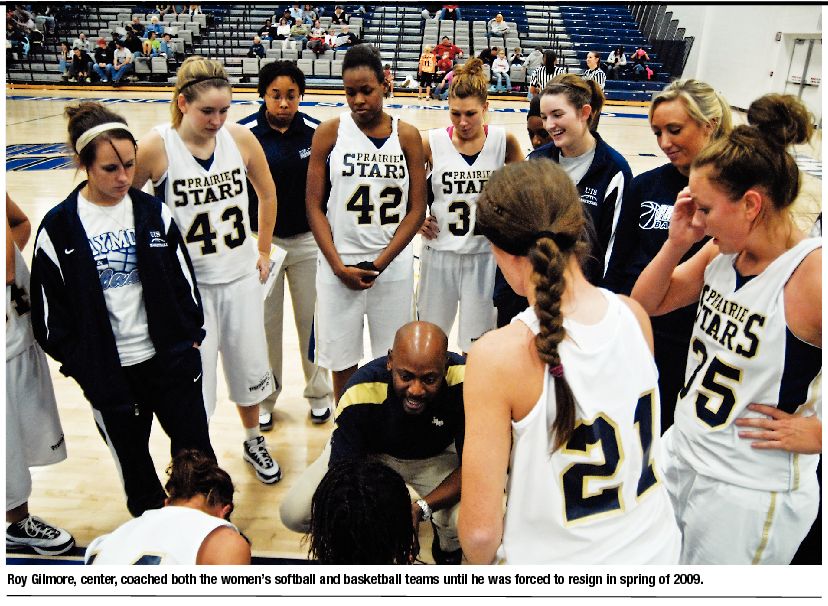

Coach v. athlete Hayler wrote in her report that it’s important for UIS “to develop and enforce its own policies, beyond those required by the NCAA” in order to ensure UIS’ main priority continues to be academics, not athletics. It’s an issue she feels is at the center of the non-renewal of several student-athlete scholarships by a visiting coach. The university hires coaches and faculty on a “visiting” basis when there’s not enough time to complete a full new-hire search, which was the case after Roy Gilmore and Joe Fisher, the softball coaches involved in the spring break scandals, were forced to resign. Coaches can hold a visiting appointment for up to three years.

Gilmore and Fisher had been head coaches for a total of three different teams, including the women’s basketball team, to which UIS appointed Marne Fauser as a visiting coach. Fauser worked with the existing team for one season before, in February 2010, informing six of nine players that they no longer would receive student-athlete scholarship assistance.

While the players were allowed to appeal the decision, the review was merely procedural, and dismissed basketball player Kelly Thompson, now a junior at UIS, says she still hasn’t received a satisfactory explanation as to how she failed to live up to expectations. The team owned a lousy wins record by the end of the 2010 season, but it isn’t doing much better this year, Thompson says. She alludes to UIS’ recent loss against Truman State, where former UIS player Erin Glogovsky transferred after Fauser revoked her scholarship. During the game, Glogovsky took 10 rebounds within her 16 minutes of playing time.

Citing NCAA rules that explicitly state that athletes’ scholarships are guaranteed for one year only, the university administration stands behind Fauser’s decision. Interim chancellor Harry Berman says the position of a visiting coach is much like his position as interim chancellor – just because it is temporary doesn’t mean it doesn’t have all the same responsibilities of a permanent position. A visiting professor, for instance, is required to design his or her own course and award grades to students, Berman says.

Williams, too, draws on the faculty analogy but comes to the opposite conclusion. “In my classroom, if a student is not performing … I do not have the ability to throw them out of my class and tell them they can’t come back. I have to work with them. I have to teach them. At UIS, I have to do it in an excellent fashion. I think that’s part of what I do as a teacher.” He says the same should be true of a coach and his or her team members.

Hayler agrees, asking which should come first, the coach’s desire to develop a winning team or the well-being of the student. She adds that few, if any, of UIS’ athletes will or expect to go on to play professional ball – academics are their first priority.

While Thompson says she was told she didn’t “have enough heart,” the university itself refuses to state specifically why the women lost their scholarships, something with which Williams takes issue. At other schools, he says, coaches explain why a student is no longer on a team. “At the U of I, if the starting center is not playing a game, you would know why. They would tell you. It might be a vague explanation, but you would know why.”

Hayler admits that other schools surely choose not to renew scholarships on a regular basis, but questions whether any school has ever revoked scholarships for two-thirds of a team.

When the administration cites NCAA rules that say scholarships can only be issued for one

continued on page 14