STEAL THESE IDEAS

continued from page 11

motorists and casual cyclers. We may never go bike-crazy like the city of Davis, but we can certainly learn a thing or two from their experience.

What can you do to help make Springfield more bike-friendly? The most obvious answer is to get a bike and learn how to ride it safely. That means learning the laws governing bicycle riders and learning how to share the road with cars. If you already ride, consider taking part in Bike to Work Week, May 17-21, which is being planned by the Springfield-Sangamon County Regional Planning Commission, Springfield Bicycle Club and other local organizations. Business owners can encourage bicycling by putting bike racks at their businesses. Lock your bike up when not in use, and consider registering it with the city to help identify your bike if it is stolen.

Dave Sykuta, chairman of the Springfield Bicycle Advisory Council, says SBAC and other Springfield organizations are working to identify ways Springfield can improve its bicycle amenities and attitudes. Fill out the SBAC survey on the City of Springfield website to register your opinion and show your support for cycling.

Dave Sykuta, chairman of the Springfield Bicycle Advisory Council, says SBAC and other Springfield organizations are working to identify ways Springfield can improve its bicycle amenities and attitudes. Fill out the SBAC survey on the City of Springfield website to register your opinion and show your support for cycling.

If Springfield succeeds at becoming a more bike-friendly city, other options will become viable, such as the popular bike rental program of Paris, France. For a nominal fee, sightseers can rent a bike and travel the city’s historic streets at a leisurely pace. Like Paris, Springfield has several historic gems to show off, and biking through the capital city can only enhance the experience.

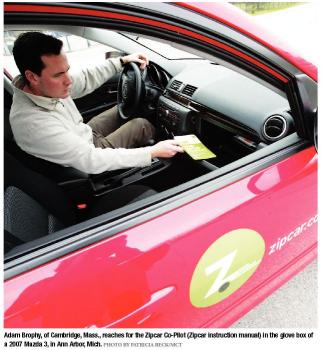

In Champaign-Urbana, Zipcars get around

The automobile has brought mobility, independence and convenience to billions of people around the world since German inventor Karl Benz unveiled what is considered to be the first gasoline-powered vehicle – the ancestor of the modern car – in 1885. But with the good eventually came the bad: pollution, congestion and the general hassles of automobile ownership.

Now, a new idea spreading across the nation claims to have solutions to those problems, and its successes in other cities seem to back up the hype. Car sharing, a concept in which users reserve a car from a pool of readily-available vehicles situated around a city, offers environmentally friendly, short-term car use to people who need the mobility, independence and convenience a car offers – but only once in a while.

Jan Kijowski, marketing director for the Champaign-Urbana Mass Transit District, says a partnership between CUMTD, Zipcar and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign has worked well.

Kijowski says the cities have invested in the program by providing special parking spaces for Zipcars and by guaranteeing the profitability of the program with subsidies that end after the program posts two consecutive quarters of profit. The program started in January 2009, but in March 2010 the Zipcar program in Champaign-Urbana posted its second consecutive profitable quarter, meaning the cities’ financial obligation is complete and their Zipcar program is now self-sustaining.

The partnership offers short-term car use to drivers who need temporary transportation, including UIUC students as young as 18, who normally could not rent a car, and international students, who may have trouble renting cars for other reasons, Kijowski says. She points out that it’s also useful for trips to the homeimprovement store when an all-day rental car isn’t necessary and a taxicab just won’t cut it.

It works like this: Users pay an annual fee that depends on their city’s arrangement ($35 for UIUC students and $50 for non-students), plus an $8-per-hour fee for each reservation. Each user gets a Zipcard that unlocks their reserved car and lets them use the service in any city with a program. Cars can be reserved for an hour or a whole day, and they can be returned to any Zipcar station.

So far, Zipcar users have been respectful of the cars, Kijowski says.

“It’s one of those neat things where a social community has developed, and people take care of the cars because they’re part of the community,” she says. “It’s rare that people will leave them messy or misuse them. People seem to be really responsible.”

Asked whether she’d recommend car sharing programs to other communities, Kijowski replies without hesitation.

“Without a doubt,” she says. “It’s obviously something that people want. We’ve had nothing but positive experiences with it.” Urbana- Champaign has reduced congestion and parking demand while improving accessibility, sustainability and infrastructure. Zipcar estimates that each car it provides takes 15 cars off the road, resulting in less fossil fuel usage and undoubtedly fewer headaches for car owners who pay insurance, registration and other fees only to use their car once in a while.

Artists in residence in Paducah

In a 25-square-block section of Paducah, a community of creatives is creating jobs, revitalizing a once-troubled neighborhood and attracting nationally-renowned talent to the small Kentucky town of 27,000. They are brought together by their love of the arts – and some pretty sweet economic incentives.

In its nine years, the Paducah Artist Relocation program has drawn as many as 70 artists from all over the nation to the city’s Lowertown neighborhood, turning what was once a crime-ridden, blight-infested city with 70 percent vacancy into a thriving, attractive economic engine. The city even won a Great American Main Street Award in early May, showcasing its success at transforming itself, in part through the power of art.

“It had basically gone into ruin,” says Jessica Perkins, marketing manager for Paducah Renaissance Alliance. “It was full of dilapidated homes and neglected rental properties owned by people who didn’t even live here.”

Perkins says the city began cracking down on code enforcement, buying up and seizing blighted properties. The relocation program sells those properties to artists with financing to purchase and rehabilitate existing structures or to build new ones. Empty lots are even available for free to artists with approved plans for new construction, and the city pays up to