whole district, the study says. But still nearly two-thirds of the department’s youth have educational disabilities, and 65 percent don’t even finish the eighth grade. Meanwhile, a lack of consistent educational programming keeps kids from developing real-world skills.

“Vocational programs are a key weakness of the system. They are not consistent through the facilities, often utilize outdated equipment and may not be training youth for jobs which exist within their home communities,” the study says.

Clarke says the lack of adequate programming undermines the reason for the department’s very existence.

“Without a comprehensive range of programming, youth are simply warehoused, and leave without adequate skills to reenter school or enter the job market,” she says.

Mental health treatment Nearly two-thirds of youth in IDJJ have both a mental health diagnosis and a substance abuse diagnosis, according to the John Howard study. Advocates say available mental health treatment simply isn’t enough.

Illinois does have programs like the Mental Health Juvenile Justice Initiative, which links youth in detention facilities to mental health services. Also, the department has begun to develop a new mental health classification system. But those reforms haven’t been completely implemented, and identifying which youth need treatment is still a challenge.

“There is a disturbing dearth of quality evaluation and validation of the tools used as mental health screening and assessment instruments,” says a March 2010 report by the Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority. The methods used to identify mental illness in youth are unproven, the agency says, meaning some kids who need help may slip through the cracks, and those who are treated may not get enough attention.

“Most respondents indicated a need for more standardized practices of screening and assessment, more comprehensive services that continue after a youth is no longer involved with the juvenile justice system, and better quality services,” the ICJIA report says.

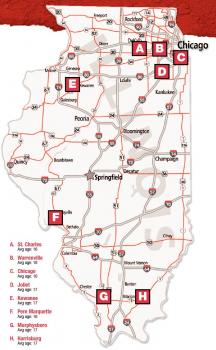

Betsy Clarke says the lack of adequate mental health treatment is sometimes replaced by the use of solitary confinement, causing more harm than good. That may have contributed to two suicides at the Kewanee and St. Charles youth prisons in 2009. Kewanee, in fact, has an entire wing devoted to solitary isolation, Clarke notes.

“This discipline technique is directly contrary to a treatment modality for youth with mental health issues,” she says.

Racial disparities Juvenile justice systems nationwide share a problem known as “disproportionate minority contact.” It’s a bureaucratic name that essentially means a minority youth has a greater chance of winding up in prison than a white youth for the same crime. Since the late 1980s, the federal government has required states to report DMC numbers and make efforts to reduce them, but Illinois has made little progress in this area. Although DMC seems to begin before youth offenders end up in prison, IDJJ becomes the de facto face of the problem because of how many minorities tend to be stuck in its facilities.

According to a December 2009 report by the Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority, 765 of the 1,362 youth committed to IDJJ in 2007 were black, a rate of 56 percent. That means black youths were incarcerated at a rate almost triple their representation in the general Illinois youth population. The same data show 459 committed youth were white and 136 were Hispanic. More recent data are not yet available from ICJIA.

From Sangamon County, 22 of the 30

continued on page 14