Home delivery

continued from page 13

as a child, and her distrust only deepened as an adult after her mother told her that she was drugged and kept from nursing all four of her children in the hospital.

“I just don’t feel comfortable with Western doctors and Western medicine,” O’Kiersey says. “They over-interfere, don’t tell people what’s going on and don’t allow people to be part of their own health care experience. With Cat, I didn’t feel that. I felt like she was there to help me, not to take over.”

Feral helped O’Kiersey pick a birth team, which included her mother and a brother who flew in from California. They attended several of Feral’s childbirth classes and learned an emergency plan in case O’Kiersey needed to be transported to the hospital. In August 1979, after being in labor for 12 hours, O’Kiersey had her first baby girl at her home in Pawnee.

If O’Kiersey had experienced complications, Feral would’ve sent an apprentice with her to the hospital. Neither O’Kiersey nor the apprentice could mention that Feral had been involved in the homebirth.

Feral had become an advocate for patients’ rights, appearing in public and on talk shows to promote, among other things, women’s right to nurse their babies and their husbands’ right to stay with them in the delivery room.

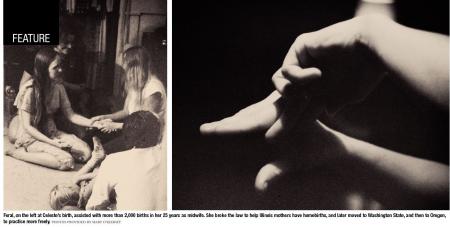

Her public advocacy led to an investigation, she says, and in the fall of 1977, she was subpoenaed by the state of Illinois for attending homebirths as a midwife. Feral was asked to supply records listing everyone who had attended her childbirth classes, as well as anyone who attended homebirths.

Feral expected a search warrant to follow, she says, so she stopped keeping records and gave all prenatal and labor records to her patients.

“In a way, it made me a more conscientious midwife,” Feral says. “I never lost a baby. I never had a birth injury that caused long-term damage. And I certainly never lost a mother.

“Probably having started midwifery being terrified of being arrested helped to make me more careful. I would like to think that I would’ve been anyway, but it didn’t hurt that I was nervous.”

Despite the law, Feral says she reached out to a few “sympathetic” doctors in Springfield. Dr. Victoria Nichols-Johnson, an obstetrician/gynecologist who recently retired after 33 years at the Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, supported natural childbirth and allowed Feral to refer problempatients to her if needed.

“Most OBs probably would not back up a lay midwife, and actually, because of the feeling at the time, I was unable to officially back her up,” Nichols-Johnson says. “That would have been approving her practice.”

Sangamon County also disapproved of Feral’s practice, refusing to give her daughter a birth certificate. Years later, when Tanner was 13 and needed a delayed birth certificate for her driver’s license learner’s permit, Feral used a copy of the 1980 Illinois Times article to prove her existence.

Feral’s house was never searched and she was never arrested, but after she moved to Washington State in 1981, she heard that a few of her apprentices had been arrested for assisting homebirths. The state’s case against her was eventually dropped in 1982.

The same year, the Association for Childbirth at Home asked her to travel around the country to conduct five-day intensive seminars for midwives-in-training. She went from direct service, she says, to impacting hundreds more babies by teaching new midwives.

Feral had her fifth and final child in a hospital in 1988. She had moved into a new house the day before she went into labor, so having a baby there was out of the question. Since Feral had attended births as a midwife in the hos-