Nuclear power revival?

continued from page 13

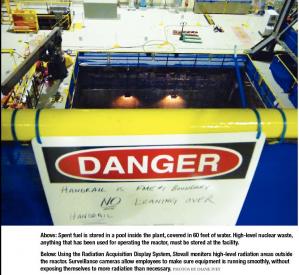

Spent fuel has been stored in the station’s pool since the station started producing electricity in 1987. Regulations state that the station must maintain enough space to put every piece of fuel in that pool. Clinton is scheduled to reach storage capacity by 2018. Once the spent fuel pools are filled to capacity, Exelon requires the stations to switch to another storage method. Used fuel may also be stored in dry casks, which trap the spent fuel rods in transportable metal canisters, which are inserted into concrete storage bunkers.

Recently, the Illinois Attorney General’s office reached a settlement with Exelon resolving the environmental consequences of radioactive tritium leaks in groundwater at the company’s Braidwood, Byron and Dresden plants. Tritium, used in nuclear fission, leaked out of underground pipes that carry wastewater away from the power stations. It can be dangerous if inhaled, ingested, carried in water or absorbed through the skin. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, exposure to tritium increases the risk of developing cancer.

The company will pay more than $1 million to resolve the complaints. Though the plant says the leaks were isolated incidents, Kraft says he sees it as a chronic symptom of the storage problem.

“Pollution of groundwater sources is not a good way to conduct business,” Kraft says.

Kraft says the tritium leaks show this system is yet to become foolproof.

“We’re of the mind that this needs to be slowed down and examined,” he says. “We’re not confident that the designs are going to be safe enough. We’re not confident in the way they’re constructed and built.”

Currently, Exelon Nuclear is licensed to build a second reactor at Clinton Power Station, but can’t proceed with plans due to the state moratorium. According to Exelon’s research, maintaining nuclear energy’s current 20 percent cut of the nation’s power-generating capacity means that three reactors must be built every two years, staring in 2016.

Kraft says the state can avoid ever building another reactor, if it could just harness its wind and solar power potential.

“We probably don’t need to build another nuclear plant ever if we aggressively use everything we have,” he says. “It’s the least contentious and at best a very optimistic way to proceed.”

Kraft’s biggest worry is the availability of water in a world that’s already seeing the effects of global warming. In a global warming world, higher temperatures, more droughts and erratic weather events could contribute to a lack of water in the Midwest, he says.

“If we hitch our wagons to the nuclear horse, we may not have water to operate on,” Kraft says. “People say nuclear energy is green energy because it emits less carbon dioxide, but holding your breath is also a solution to that problem. CO2 is not the only factor to be considered here.”

With 675 employees on the payroll, the Clinton station is a substantial piece of the area’s economy. Most workers hail from DeWitt, McLean, Macon and Champaign counties. The station paid $9.2 million in property taxes last year, and has donated $70,000 per year in direct financial support to local civic organizations, schools and charities.

The large size and scale of nuclear power plants mean it’s necessary to hire hundreds of construction employees, thus spurring job creation, Kanavos says.

“Studies show that 10,000 people contribute to building a nuclear power station,” he says. “There’s a long-term, positive impact. We’d like to have the opportunity to build that in Illinois.”

Kraft says his anti-nuclear group isn’t insensitive to the jobs issue, but equal numbers of employees can be hired for wind, solar and other clean energy operations. About 48 percent of Illinois’ electricity is generated from nuclear power, according to the Nuclear Energy Institute.

“We have to stress aggressive energy conservation and efficiency, utilizing green technologies to enhance jobs,” Kraft says.

Harris, who has worked for Exelon since 1998, says the station has a deeply rooted connection with the surrounding natural resources. The state’s Department of Natural Resources has an office on the edge of Lake Clinton, where the power station’s welcome center used to be.