The state’s dirty little secret

continued from page 13

start with our own state Capitol building.”

The power plant doesn’t make electricity, but steam that is used for heating and cooling the Statehouse and 22 other buildings located around the Capitol complex.

Built in 1948 and coming online two years later, the system, which also makes hot water and chill water for air conditioning, was at that time the cheapest way to distribute steam throughout the complex.

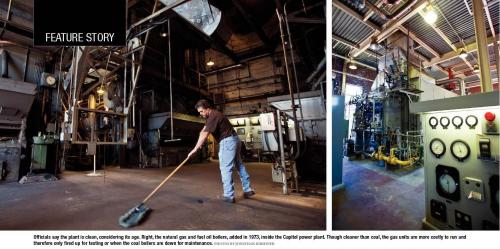

There are a total of five boilers — three coal boilers and two natural gas units. On summer days, only one of the coal boilers needs to run. The natural gas boilers, installed in 1973 at the height of the energy crisis and designed to also run on diesel fuel, are used sparingly because coal remains the cheaper fuel. Officials at the plant, run by the Illinois secretary of state’s office, like to say the plant is clean — for one that’s 60 years old. Bruce Biggs has been the chief engineer for the Capitol complex since April.

“We’ve spent a lot of money over the years to stay in compliance. We’re proud of this building because we run it as efficiently as we can,” Biggs says. A baghouse, which collects fly ash, was added in 1990. In 1999, an opacity monitor that measures the toxins emitted from the plant was installed, with the reports generated going to environmental regulators quarterly, semi-annually and annually. The plant is not equipped with sulfur-reducing scrubbers, however.

“If you ever notice, you don’t ever see any black smoke coming out of our stack. It’s real clean,” Biggs says. Additionally, a sample from every truckload of coal that is delivered from Tri-County Coal mine in Farmersville is sent to the Illinois Department of Natural Resources mines division for testing. The plant burns through approximately 14,000 tons of high-sulfur Illinois coal each year. (To provide some perspective, CWLP uses 700,000 tons in the same time period.) Finely ground coal ash that is left over at the end of the process, along with the dust from the baghouse, is trucked back to the Farmersville mine for storage rather than stored on site. Of the large black piles of coal outside — 10 to 15 days worth, in case of a snowstorm or workers’ strike — Biggs says there are no requirements to cover it or lock it away.

Verena

Owen, chairwoman of the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign in Chicago, says the biggest problem with the Capitol power plant is quite simple.

“It’s close to people!” she says. “There are always health concerns with any kind of coal combustion. Certainly they are not in the magnitude of a full outright power plant but they do emit things like particulate matter and mercury. We know that mercury is a terrible pollutant. I’m not saying there’s a ton of mercury coming out of small plants but it’s an additional concern.”

The Capitol plant’s bag houses, she points out, do not mitigate sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen oxides (NOx), or mercury.

Another concern she has is coal dust blowing around. “I would think it’s probably more of a nuisance but I wouldn’t want to breathe it. Intuitively, it doesn’t sound like something I would want in my lungs.”

In recent years, the Sierra Club has fought successfully to keep about 100 new coal-fired power plants from being constructed in the