Reassessing governor’s post-Katrina legacy

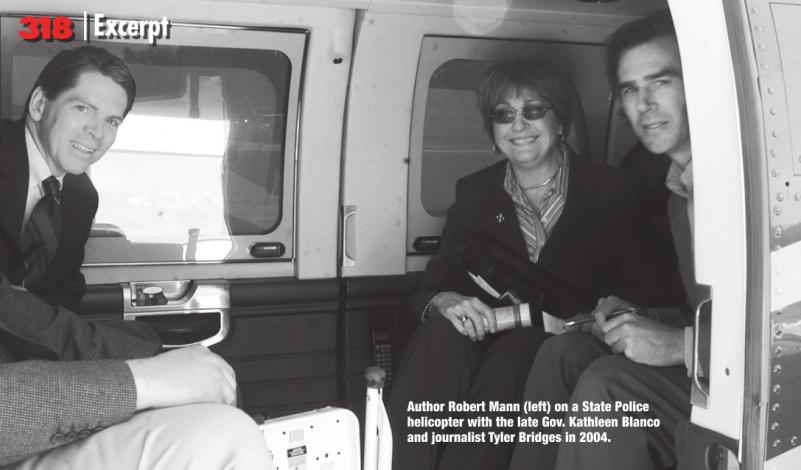

As the 16th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina approaches, the following is an excerpt from Robert Mann’s new memoir: “Backrooms and Bayous: My Life in Louisiana Politics,” looking at how the late governor handled the crisis.

Governor Kathleen Blanco’s administration had two periods. There was pre-Katrina, during which she devoted herself, among other things, to creating jobs and reforming education and juvenile justice. Post-Katrina, there was nothing but recovering from Katrina and Rita. After the searchand-recovery phase, the work of restoring south Louisiana began.

To secure the billions in recovery aid Louisiana needed from the federal government meant Blanco would be forced to testify before congressional committees investigating the errors and missteps by officials at every level of government. She also would have to make a dozen or so trips to Washington to lobby congressional leaders and Bush administration officials for the money, especially after the initial appropriations bill awarded much more per capita to Mississippi than Louisiana.

To secure the billions in recovery aid Louisiana needed from the federal government meant Blanco would be forced to testify before congressional committees investigating the errors and missteps by officials at every level of government. She also would have to make a dozen or so trips to Washington to lobby congressional leaders and Bush administration officials for the money, especially after the initial appropriations bill awarded much more per capita to Mississippi than Louisiana.

For Blanco, the job was grueling and often humbling. On virtually every trip, she went to the White House to plead for funding from officials who attacked her or who doubted that Louisiana government was honest or efficient enough to spend properly the rebuilding dollars we requested. In these visits, she showed her steel, once threatening to blast President George W. Bush in a press conference on the White House driveway if his aides did not give Louisiana what it needed. They quickly relented when they realized she wasn’t bluffing. Then, she would trudge over to Capitol Hill for meetings with Democratic and Republican leaders.

The stress on Blanco was clear. The suffering she witnessed weighed on her constantly. She had to know that Katrina would be her legacy, for good or bad. And bad it was, at least in the early months. During this time, I think she looked for and treasured moments when she could forget about Katrina and Rita for a few hours.

Days or evenings during which she could truly relax were rare, but I witnessed one of them on a trip with her to Washington in December 2005. Blanco spent all day testifying before congressional committees and

meeting with members of the House and Senate appropriations committees.

Like all these days in DC, it was long and exhausting.

That

evening, she and the staff went to dinner and then retired to a large

condo in northwest Washington owned by a friend of Aprill Springfield

(Blanco’s future daughter-in-law, who had recently joined the staff).

After

a review of the day, Aprill and the other staffers drifted away for

bed. Finally, it was just Blanco and me. She was as relaxed as I had

seen her in months. We talked for a while. Even though I was sleepy and

looking for an excuse to retire, I couldn’t leave her until she was

ready to turn in.

Eventually,

we discovered that the owner of the place had a media room with an

impressive collection of movies on DVD. “You want to watch a movie?”

I

asked. I knew she was a night owl, so her answer was not in doubt. We

combed through the DVDs and settled on “Pirates of the Caribbean: The

Curse of the Black Pearl,” a hilarious film starring Johnny Depp. For

over two hours, we laughed like children.

It

was a reminder that, at her essence, Blanco was a normal person who

hadn’t expected that her legacy would be helping an entire state get up

off its knees. But as a person of deep faith, she believed that God

called her to serve in that way.

I

don’t mean that Blanco thought God made her governor. She didn’t have a

grandiose view of public service. But like many believers, she saw

herself as one of God’s instruments. If her lot in life was to be the

governor who responded to Katrina, she would do it with resolve and let

her faith guide her.

More

typical of Blanco’s schedule was her whirlwind trip to the Netherlands

in January 2006 – along with senators Mary Landrieu and David Vitter,

several New Orleans-area parish leaders, and other local officials – to

learn how the Dutch deal with the constant, centuriesold threat of

water. With its many miles of intersecting canals, Amsterdam is a

beautiful example of a city that coexists with water, unlike New

Orleans, which depended only on floodwalls and levees, hoping the

barriers held.

A state

trooper and I accompanied Blanco on this trip. The delegation left New

Orleans on a Monday, arrived in Amsterdam on Tuesday morning, toured the

country over Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday, and flew back on Friday.

Blanco returned a day early, on Thursday morning, leaving me to represent her on the final day.

She

never recovered from the jet lag caused by flying east over the

Atlantic before she endured the jet lag of flying in the opposite

direction. She must have been exhausted when she returned to work on

Friday. I don’t know how she did it.

By

the time Blanco would die 14 years later, the assessment of her

leadership had softened. Historians and others who examined what

happened during and after Katrina began to recognize that Blanco’s

leadership – while not perfect – was far better than Bush’s, who left

the White House in disgrace, and New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin’s, who went

to federal prison a few years later.

Those

who looked at Blanco more dispassionately applauded her for leading the

state with dedication and integrity during its most difficult days.

They recognized she fought for Louisiana when some in Washington –

including the Republican Speaker of the House – wanted to give up on New

Orleans and the rest of the state. Blanco never gave up. Until the last

day of her term, she worked with relentless passion to restore her

beloved state.

Thirteen

years after Katrina, on Dec. 20, 2018, as Blanco was dying of the

cancer that would take her life in August 2019, I wrote her a letter:

“What I really want to tell you is that Louisiana was blessed to have

you as governor at that time in history. Your legacy will be one that

your children and grandchildren will be proud of. If I have

anything to do with the writing about the history of that time (and I

plan to), I will do my best to make it abundantly clear what a wise and

tireless leader you were for our state.”

I’m

happy Blanco lived long enough to see the assessment of her leadership

evolve. Because everyone knew she only had a year or two to live when

her cancer returned in late 2017, she read and heard some of this

reassessment, including from then-Times-Picayune columnist Jarvis

DeBerry, who said he regretted writing a column critical of Blanco.

Historian

Douglas Brinkley, who taught at Tulane University at the time of

Katrina, said in April 2019, “I think Kathleen Blanco was a true hero of

Katrina.” Republican state Sen. Danny Martiny of Metairie was also kind

in describing her leadership. “In the end,” he said in 2016, “I think

you’ll find that this lady was a leader who was dealt a bad hand and did

the best she could.”

As

I wrote in the New Orleans paper Gambit the day she died, “[She] wasn’t

the boldest or most charismatic politician Louisiana ever produced, but

Kathleen Blanco may have been the most empathetic, compassionate person

to serve as Louisiana governor.”

Robert

Mann – a political historian, former journalist and longtime U.S.

Senate aide – was Gov. Kathleen Blanco’s communications director and now

holds the Manship Chair in Journalism at Louisiana State University.

Learn more about his memoir, “Backrooms and Bayous: My Life in Louisiana

Politics,” at: BackroomsAndBayous.com.