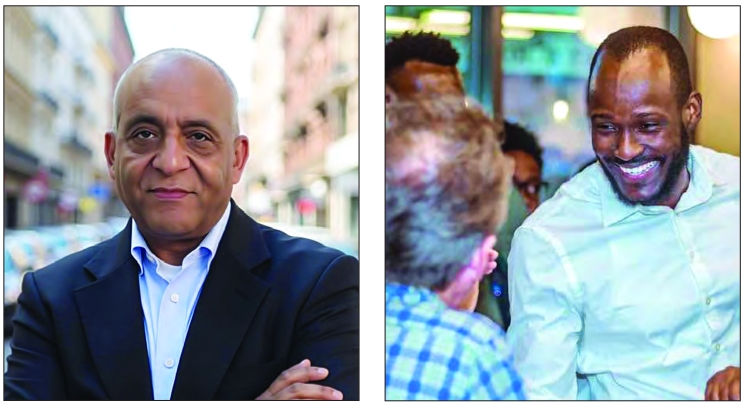

Brockton mayoral candidates Moises M. Rodrigues (left) and Jean Bradley Derenoncourt. When the City of Champions votes Nov. 4, for the first time in the city’s history two Black men will top the ballot: Moises Rodrigues and Jean Bradley Derenoncourt.

Both sitting city councilors are vying to succeed Robert Sullivan, Brockton’s 50th mayor. He made way in March.

Speaking to the Banner last week, Rodrigues and Derenoncourt agree on the interlocking issues Brockton must confront: preparing the next generation, addressing homelessness and restoring economic activity.

To succeed, the next mayor must mobilize a cross-cultural coalition in a city renowned for diversity. Both leading candidates bring lived experience to that task, having arrived from Angola and Haiti, respectively, as youths.

Unfortunately, a better future may require a complete transformation.

“Voters are apathetic,” said Luz Villar, the third-place finisher in Brockton’s September primary. Citing a “10% voter engagement rate,” she lamented “the lowest voter turnout ever.”

A former aide to U.S. Rep. Ayanna Pressley, Villar endorsed Derenoncourt. “We have low civic engagement and we need more civic education,” she said.

In Brockton, that duty falls to the mayor. “It’s their responsibility to talk to everyone, engage everyone,” she said. Villar urged the next mayor to be “the gold standard of communication.”

That, she theorized, has “a ripple effect into your constituency.” Participation begets personal investment and more engagement. Without oversight, she posited, turmoil is inevitable.

Recounting recent issues in the school administration, Rodrigues said “financially, we’re not in the healthiest of places.”

He expects to advocate for Beacon Hill to cover school transportation costs. Paid entirely by the city, transportation spending has roughly tripled since he was first elected to the City Council.

One bright spot, Rodrigues said, is how Brockton “graduated around 1,000 kids” last year, “70% of whom went on to full-year colleges.” Many others took up national service or skills trades.

Derenoncourt emphasized solutions for Brockton Public Schools, acknowledging, “we do have a problem within the school system.”

Pledging to hold employees accountable to spending wisely, he also hopes to “invest in the school system.”

Derenoncourt believes afterschool programs like art, music and sports can keep kids off the streets.

For funding, he also looks to Beacon Hill and is hoping to convince lawmakers of the critical need for school funding in Brockton and other Gateway Cities.

Better education could recoup dollars, since funding follows enrollment.

“Revitalizing downtown, helping the schools,” said Mary LaCivita, Derenoncourt’s campaign manager.

“Underneath all of those issues is helping the kids do what they should be doing.”

“It’s our responsibility as adults to give them things to do,” she said.

LaCivita raised a recent Brockton High School graduate. While praising sports and debate, she said “we don’t have enough of that, and there’s not enough money.”

“People will move to a community and buy houses, and pay more for houses,” she said, “if it’s a good school system.”

“As a kid, when I first moved here,” Derenoncourt recalled, “the library was the place for me to go.” He learned English in a Brockton Public Library program that is now defunct.

He noted Brockton’s Adult Learning Center, where English classes command a “waiting list.”

He said the free access to books, computers and the internet through the Brockton Public Library are “a foundation that everybody needs.”

During his time in office, Derenoncourt fought to defend Brockton’s public libraries from budget cuts that would have shuttered two branches. He currently serves on the library’s board of trustees.

“We have a lot of homeless kids in the city, and the only environment that gives them a place where they can study, do their research, is the library.”

Camping and loitering in Brockton

The leading candidates voted differently on City Council ordinances to ban camping and loitering. Initially passed last November, the ordinances included a $200-per-day fine for camping on public property, with a $25 fine for loitering.

“There’s not been one fine passed out at all,” LaCivita argued against the move. Nonetheless, she recognizes the costs of the status quo. “Most people are shopping less in places where they know there are a lot of homeless people.”

While Mayor Sullivan vetoed the ordinances over concerns of the criminalization of homelessness and the constitutional rights to public space, the City Council overrode the veto at the beginning of 2025.

Derenoncourt sees homelessness as a city, state and national issue, “not something that can be fixed by one person.”

The work, he said, is minimizing the situation while service providers connect person-to-person. He envisions enlisting hospitals, the state and Veterans Administration alongside frontline groups, like Father Bills & MainSpring.

Promoting a housing-first approach, he sees alignment with former President George W. Bush, who championed compassionate conservatism.

“I am in favor of a housing approach,” Derenoncourt summarized, “as opposed to the jail approach.”

Bottom line, “we are human and we gotta be able to treat people accordingly,” Derenoncourt insisted.

“We are not anti-homeless,” Rodrigues argued, “we are anti- some of the behavior” tied to homelessness.

Noting that basic sanitary expectations apply to all, he noted that business owners could leave. When they “pack up their bags,” he said, “we’re stuck with one more empty storefront.”

Rodrigues hopes to reinstitute “clean teams,” or red shirts, that employ people living in shelters to clean up the downtown area or remove graffiti.

“Everyone complains how dirty the city is,” he said. Arguing that the perception of crime inhibits economic activity, he urged positivity.

One business owner, Fred Fontaine, has known Derenoncourt since high school graduation. The Haitian elder is supporting Rodrigues.

“Whoever this mayor is going to be,” Fontaine expects, will have “carry over” issues from the current administration. The next mayor will “need a lot of help from everybody” since “by himself, he cannot solve those issues.”

He recommends the next mayor maintain an open door to businesses and “keep this city clean.”

“Starting from homelessness, crimes, street cleaning,” he said, “get people together to really make the best of it.”

He believes in “tough love” for those living rough. “Encouraging them to stay on the street is not helping the city.”

Fontaine said that Father Bill’s shelter at the corner of Main Street and Spring Street relocated in May. “It’s a brand-new shelter. There’s space for everybody. Whoever stays on the street,” he said, noting that some homeless people have harassed local businesses, “you go after them.”

Fontaine called on state legislators for aid. “The state has to be able to come over and help you,” he explained, “we need help in Brockton.”

Earlier this month the Massachusetts Municipal Association published a statewide assessment that found that “among gateway cities, the core problem is that demand for real estate is limited, and property values are relatively low.”

“That makes it hard to raise money through a direct tax on property values.”

“Downtown Brockton is dead,” Derenoncourt stated. He was especially concerned with inactivity after work.

“I understand that people might not feel safe given the situation,” he admits. His plan spares the homeless from official pressure, while leaning on police and fire departments, and the community, to do their jobs.

“People need a city that is clean, that is safe; a city where you can send children to school,” Derenoncourt explained.

That, he hopes, could kickstart change. He endorsed “paying the police, the fire, the teachers” while protecting taxpayers. “I will not let anybody intimidate me” for a raise, he proclaimed, “especially if we don’t have it.”

“One of the largest issues” for Rodrigues is the balance between residential and commercial tax. “Residents are responsible for over 70%.”

He hopes to relieve homeowners by expanding the tax base. “Growing that commercial tax base,” he said, “not increasing taxes.”

Derenoncourt also opposes tax hikes.

Rodrigues plans to “develop every single piece of property that needs developing.” He sees the Trout Brook project, formerly a CSX Railyard, as a place for more housing.

Derenoncourt will convene residents to discuss what the project could provide. He favors green space “where our children can go and play.”

Villar says Brockton needs more youth programs. She said while existing offerings are “great” and “effective,” there aren’t enough resources.

“We’ve got to look at sports or team-oriented activities,” she suggested. “An innovation center here would be amazing.”

Villar suggested “community anchors,” like the Cape Verdean Association of Brockton that Rodrigues leads, can commune with minority populations. With language skills and a welcoming attitude, these programs “meet people where they’re at.”

Brockton water supply debated

The candidates differ on the strategy to secure future water supplies. Brockton pays about $9 million yearly for water from Aquarias in Dighton.

“We have three years left in that contract,” Rodrigues said, “and that’s another $27 million.” He estimates savings if Brockton buys the plant.

“You’re looking at $3 million” annually as a “note payment, plus $3 million to operate it,” he argued. “We’re saving $3 million right off the bat.”

In 2024, Aquaria’s plant had $6.2 million in operating expenses. Over seven years net revenue exceeded expenses by about $7 million total.

“The city of Brockton is not in the financial state to purchase this plant,” Derenoncourt argued. “We have to look at other places. It’s not a monopoly.”

Since the state requires Brockton to maintain a backup water source, Rodrigues sees no choice. “They have us by the short hairs,” he said.

Brockton entered an Administrative Consent Order with the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection in 1995.

“There are no other water sources,” he insisted. Silver Lake, Brockton’s primary water supply, is “50% below what it needs to be.”

Even though Brockton is the desalination plant’s sole customer, he doubts the city can get a better deal after the current contract expires in 2028.

Reached by phone last week, a DEP official expressed familiarity with the Aquaria documents, suggesting the state is studying its mandate.

The candidates appeared together this week at a forum hosted by the Greater Brockton Young Professionals.

The moderator, Rahsaan Hall of the Urban League of Eastern Massachusetts, is focused on the possibilities.

“For the Blackest city of New England, to have its first elected Black mayor — it’s an exciting prospect,” he said.