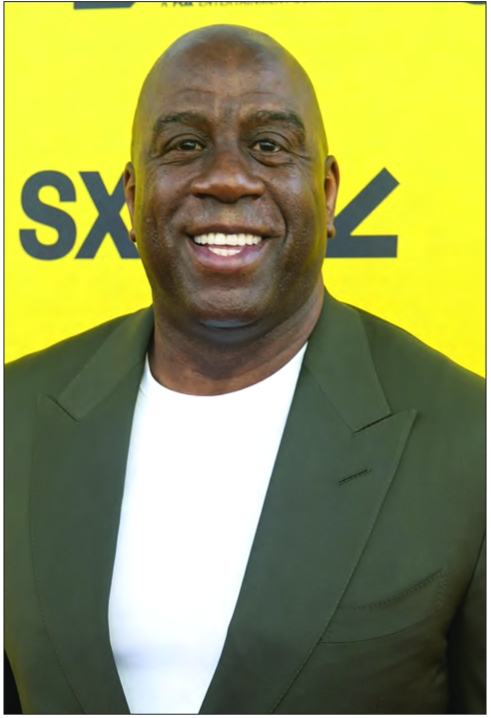

Earvin Johnson announced his HIV status on November 7, 1991.

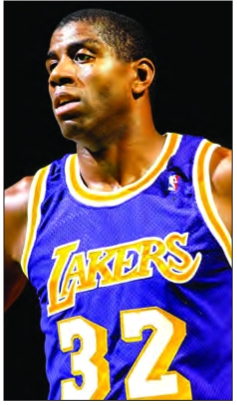

Magic Johnson with the Los Angeles Lakers in 1987.

Worries young people in Black community have learned wrong lesson from his long-term survival

Earvin “Magic” Johnson wants to spread the word to Black Gen Z’ers — especially those who think HIV/AIDS is no big deal because an NBA legend like him has lived with it for more than three decades. Although it is no longer a death sentence, he says, it’s still killing Black people, and should be taken seriously.

By making it to his 66th birthday, “I was the curse and good for the disease,” said Johnson during his keynote speech Friday at the National Minority AIDS/HIV Conference in Washington, D.C. “They saw me, and then they saw that I had been living this long life. But then they said, ‘Oh, if I get HIV, I’m gonna be good, because Magic is good.’ And we can’t look at it like that.”

The data backs up his warning: Black people represent around 13% of the U.S. population, but account for roughly 39% of all new HIV diagnoses. Four in 10 people currently living with HIV are Black, and 43% of all HIV-related deaths are Black — more than any other racial/ethnic group in the United States. And with President Donald Trump’s proposed budget cuts, drugs like the ones that kept Johnson alive could be harder to get for low-income Medicaid patients.

Black people must be careful, Johnson said, because the virus “is out here in a big way in our community.”

‘The curse and the good’

In a half-hour talk that was part sermon, part call to action and part locker-room pep-talk, Johnson recounted his journey from what he himself considered a terminal illness to his longevity. Strolling into the audience with his microphone, Johnson discussed the need to fight disinformation in the Black community, how he intends to continue advocating for funding to fight the virus and keep the public engaged.

An NBA Hall of Famer, five-time world champion, Olympic gold medalist and wealthy businessman, Johnson is perhaps the highest-profile person living with AIDS since the virus emerged as a public health threat in the 1980s. His diagnosis, however, literally changed the face of the disease, transforming it from a disease that was typically associated with white gay men — and that carried a lot of stigma.

Johnson put a famous Black face on a disease that was devastating communities of color, but received relatively little attention. For Black America, the epidemic was already shifting — cases among white gay men were slowing. But infections among Black women and heterosexual Black men, particularly in the South, were climbing fast.

Not a death sentence

Three decades later, science has transformed HIV into a chronic condition that can be managed with medication. But for Black communities, the burden remains out of proportion.

Black men are diagnosed with HIV more than seven times as often as white men, while Black women face rates up to 18 times higher than white women. Public health experts point to systemic barriers — poverty, racism, stigma and unequal access to consistent care — as key drivers.

There has been progress: between 2018 and 2022, new infections among Black people dropped 18%. Yet Johnson’s reminder is clear: The virus may no longer be the death sentence it once was, but in Black America, HIV remains a mirror of inequality.

“It’s definitely changed.

We still have obstacles,” said Johnson, noting that when he began treatment, there were few Black patients, even fewer doctors or clinicians and a lot of misinformation in the Black community. But along with improved drugs and growing awareness, “I hadn’t seen this many minorities [fighting the virus]. What a blessing that is, absolutely.”

Funding cuts and obstacles ahead

Still, Johnson predicts tough times lie ahead — particularly given President Donald Trump’s funding cuts to Medicaid, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s hollowing out of the nation’s public-health apparatus and the Trump administration’s general hostility to science and medical research.

“It’s only going to get harder because [Trump] is trying to cut the funding,” he said. “But we’ve got to stay together, we’ve got to work together. We’ve got to pool our resources together and continue this fight. And we’ve got to keep it at the forefront.”

Since the discovery of effective treatments, the HIV-AIDS virus “has kind of slipped” from the national agenda, Johnson says.

“We’ve got to bring it back up, so people talk about it.”

The key, he said, is “education, education, education,” especially among Black men. Early detection was the key to his longevity, allowing his doctors to “jump on it” and maximize his odds of keeping the disease at bay.

More Black men, he added, should follow his example.

“Black men — make sure you get your physical,” he said. “Make sure you understand your status. Take your meds and do all the right things” to get and stay healthy.

This article originally appeared on Word in Black.