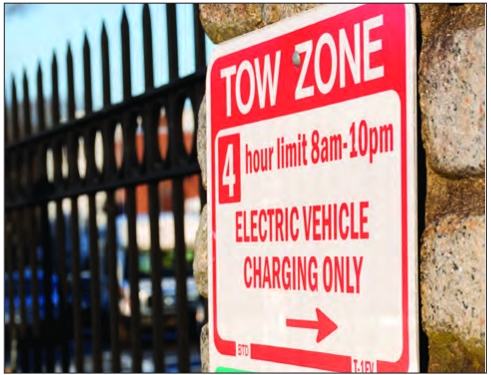

A

sign marks an electric vehicle charging station at a municipal lot off

Mattapan Sq. in March, 2024. The state’s Electric Vehicle Infrastructure

Coordinating Council released a new assessment, paired with $46

million, to support expansion of chargers for electric buses, trucks and

vans across the state.A new state report identified goals around how and where to increase Massachusetts’ electric vehicle charging infrastructure.

That document, the second biennial assessment from the state’s Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Coordinating Council, was released Aug. 12 and focused on introducing more infrastructure for larger electric vehicles and expanding a charging network to parts of the state, like in the central and western regions, that currently have limited access.

Along with the assessment, the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection announced $46 million in allocations through the 2027 fiscal year to take a stab at some of those goals.

“Our goal with the funding side is simple: It’s to take this EVICC assessment and start making it happen,” said MassDEP Commissioner Bonnie Heiple.

The assessment and new funding have a focus on expanding infrastructure for charging medium- and heavy-duty electric vehicles — everything from local delivery trucks and shuttles to buses and freight trucks.

“We know that these are the most polluting vehicles on our roads,” Heiple said. “This is the diesel smog; this is the particulate.”

When it comes to reducing transportation emissions, tackling those larger vehicles could make a dent.

According to a report from

the Union of Concerned Scientists, published in February, across the

country medium- and high-duty vehicles make up about 13% of vehicles on

the road, but account for about 30% of climate warming emissions. That

report identified medium- and heavy-duty vehicles as the largest source

of nitrogen oxides, one kind of greenhouse gas.

State

officials said they hope the emissions reductions that will come with

electrifying those larger vehicles will especially benefit

communities of color and other environmental justice communities, which are exposed to toxic air at a higher rate.

A

2021 article in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, found that

low-income communities of color in the United States are exposed to 28%

nitrogen dioxide, which can lead to cardiovascular disease, asthma and

other respiratory ailments, compared to their wealthier white

counterparts.

In

Boston, neighborhoods like Nubian Square have a history of standing up

against air pollution from a high quantity of diesel-powered buses.

For Massachusetts, those

gains represent an important step toward reaching state-established

goals for vehicle electrification. The state’s Clean Energy and Climate

Plans for 2030 and 2050 established a goal of reducing transportation

emissions of 34% below 1990 by the end of the decade and by 86% by 2050.

The

report “gets a lot right,” said Samantha Houston, a senior manager for

the Union of Concerned Scientists Clean Transportation program, pointing

to elements like the focus on medium- and heavy-duty chargers, as well

as the shifts in the electrical grid that will be required and a focus

on best practices surrounding equity.

The

focus on increasing charging infrastructure for larger vehicles stems

from concerns the state heard around its efforts to push for the switch

to electric medium- and heavy-duty electric vehicles, Heiple said.

“That

was largely premised on the notion that there’s no charging for these

vehicles,” Heiple said. “How can you force a switch when states are not

ready in terms of the infrastructure that you’ve built out? So we’re

being really thoughtful about that in Massachusetts.”

Of

the total $46 million in DEP funding announced by the state, $30

million is slated to go toward supporting charging infrastructure for

medium- and heavyduty vehicles, alongside chargers on secondary

corridors — high-traffic roadways that are not already covered by other

state plans for electrification.

The

remaining $16 million will support the installation of EV chargers

through the state’s electric vehicle incentive program through the DEP.

That program supports installation of charging stations, including costs

like buying the infrastructure and the labor required to install it.

Previously,

the program supported the installation of chargers at locations like

school campuses, at multiunit housing complexes and workplaces.

Houston

said charging for larger vehicles is, in many ways, similar to charging

so-called “light vehicles” — think a personal car — though some

elements like the energy needs differ. According to the Great Plains

Institute,

a nonprofit working on accelerating the transition to netzero

emissions, medium- to heavy-duty electric vehicles can use 0.5 kWh to

5.2 kWh per mile. Light-duty EVs use 0.2 to 0.4 kWh per mile.

That greater energy usage means bigger batteries that can cost more and require longer charge times.

Like

personal electric vehicles, medium- and heavy-duty EVs can charge “at

home,” wherever they sit overnight — for example at a truck depot — as

well as at truck stops along their routes. But Houston said that

vehicles like trucks might have additional moments to charge, like when

they’re loading and unloading.

The

assessment also identified a need to expand the deployment of EV

chargers — it estimated that the state needs to triple its pace — even

as across the country the expansion of electric vehicles faces backlash

from the federal government under the Trump administration, which is set

to end federal tax credits for new electric vehicle purchases through

its budget reconciliation act, formerly called the One Big Beautiful

Bill.

And,

in February, the administration froze funding for the federal National

Electric Vehicle Infrastructure program, which provides money to states

to install chargers. A coalition of about a dozen states sued in

response, and on Aug. 15, the administration reopened the program.

But

the report was heartening, Houston said, as an indicator of continued

state support, even as the federal government pulls back on electric

vehicles.

“That’s not

what we wanted to see, especially in this moment, when we had started to

see some acceleration of progress on those fronts — progress which, I

should say, we desperately need to address global warming as well as

local air pollution issues,” Houston said.

State officials dismissed the federal pullback on electric vehicles.

“We

have solid science on this; we know about the threats to public health

from pollutants emitted from the transportation sector; we have a way to

address it,” Heiple said. “To ignore this entire market sector, to

basically attempt to put it on ice and just roll back the clock and roll

back the standards to earlier times that have gotten us in a really bad

situation, is tremendously unhelpful.”

While

the reduction in federal support may slow the uptake of vehicles and

the installation of charging infrastructure, Houston said she doesn’t

expect to see action around electric vehicles stop fully.

“It

really is devastating to see the brakes being put on this progress at

the federal level, but it’s a global market,” Houston said. “And action

from states like Massachusetts can also help continue to move us

forward.”

According to

Cox Automotive, as of April, electric vehicle sales continued to grow

in the first part of the year. In a market insight report for the first

quarter of 2025, Cox reported the sale of nearly 300,000 electric

vehicles. At the same time in 2024, Cox reported the sale of 268,909 new

EVs.

“The fact that

we’re continuing to see adoption at similar rates, I think, makes the

point that … EVs are really here to stay,” said Josh Ryor, assistant

secretary of energy for the Executive Office of Energy and Environmental

Affairs and chair of the EVICC.

Actions

by individual states, like the funding and report from Massachusetts’

EVICC, will also help support the profusion of EVs, she said.

The

pullback could, however, complicate the state’s vehicle electrification

goals, Houston said, even if it may not make it impossible.

State officials said that the federal shifts pose a challenge, but don’t change the state’s goals.

“The

pullback on these policies certainly doesn’t help,” Ryor said. “But we

are committed to really making sure that we are focused on what we can

control, having the biggest impact we can and making sure that our

dollars are going as far as possible.”

Houston

said that if a federal pullback keeps Massachusetts from meeting its

electrification goals, any benefits around climate and emissions will

still be worthwhile.

“If

we miss them by a hair, you know, all that progress we made still goes a

long way to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and contributing to

reducing local air pollution,” Houston said.