Documents

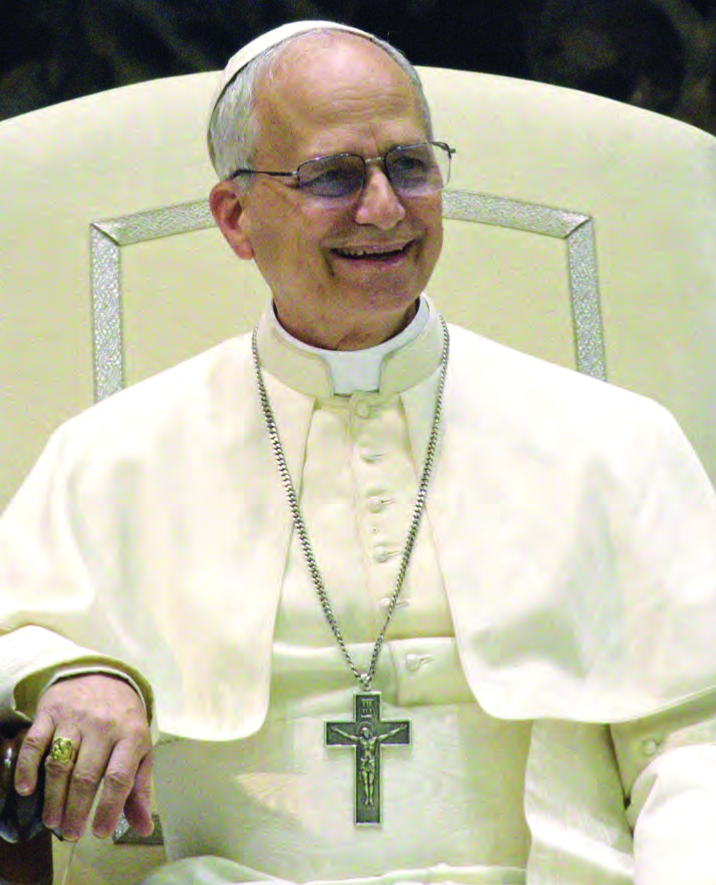

suggest that the new pope, Leo XIV, is descended from people of color

with roots in a wellknown Creole neighborhood in New Orleans.Did the Catholic church just choose its first African American pope?

That question set Black social media on fire in the hours following the election of Robert Prevost, the first American to become pontiff in the Catholic Church’s 2,000-year history.

The facts about Leo, the former Peru-based cardinal who won the papacy on Thursday, seem to say so, including documents suggesting he is descended from people of color with roots in a well-known Creole neighborhood in New Orleans.

Bolstering the case: the new pope is from Chicago, a Great Migration destination city, and was born in Bronzeville, a Black enclave once known as “the Harlem of the Midwest.”

But other facts point in the opposite direction, including Leo’s looks, his childhood in a mostly white Far South Side community in the 1950s and 1960s and the fact that his official Vatican biography has nothing about African American or Creole ancestry.

Meanwhile, his brother, John Prevost, poured icecold water over speculation about the new pontiff’s racial identification. The family, he told The New York Times, doesn’t currently identify as Black.

Ancestry vs. self-identity

That, however, did little to quell a raging online debate among genealogists, Black historians, and opinionated Black Netizens over whether Black America can — or should — claim the new pope as one of their own. It triggered speculation about whether

Leo would be compelled to publicly address his racial identity. And it

resurrected thorny, age-old questions about race, identity, and exactly

where the color line is drawn.

“Here

we go again,” said Phillipe Copeland, a professor, sociologist and

racial justice expert at Boston University. “Here’s another situation

where, potentially, it’s a chance to revisit our assumptions about what

makes race in the first place. Is it ancestry? Is it geography? Is it

language? Is it biological?”

While

most scholars acknowledge that race is an artificial construct,

“there’s a folk version of race, which is like, ‘Oh, well, you’re Black

because your parents are Black,’” he said. Both ideas, he says, live in

people’s minds “until something comes along like this.

Then

it’s like, ‘Well, wait a minute: what makes somebody Black? Is having a

Black ancestor sufficient? Is it perception from others? Is it how you

self-identify?”

At

issue is information that emerged not long after the white smoke

billowed from the Sistine Chapel, indicating the College of Cardinals

had selected a replacement for the late Pope Francis, who died last

month. As video of Leo’s first appearance at the

balcony overlooking St. Peter’s Square rocketed around the globe, Jari

C. Honora, a New Orleans genealogist, noticed that the pope’s surname —

Prevost — sounded French.

“One-drop rule”

Acting

on a hunch, Honora began digging through digital archives and quickly

hit pay dirt: Leo’s maternal grandparents, Joseph Martinez and Louise

Baquié, had been identified as Black in government documents and had

lived in New Orleans’ Seventh Ward, a Catholic stronghold teeming with

immigrants from Africa, Europe and the Caribbean. Martinez and Baquié

then gave birth to Mildred Martinez — the pope’s mother — after moving

to Chicago in the early 1900s.

“This

discovery is just an additional reminder of how interwoven we are as

Americans,” Honora told The Times. “I hope that it will highlight the

long history of Black Catholics, both free and enslaved, in this

country, which includes the Holy Father’s family.”

The

Times wrote that Leo “is not only breaking ground as the first

U.S.-born pontiff. He also comes from a family that reflects the many

threads that make up the complicated and rich fabric of the American

story.”

But that

fabric is being yanked and pulled in different directions, reviving

painful debates about race and identity in America. Some pushed back on

the belief that Leo’s lineage automatically qualifies him as Black;

others declared that, historically, people who identified as Creole did

so to avoid being classified as Black. Still others saw the

debate over Leo as a resurrection of the “one-drop rule” — a cruel, Jim

Crowera tool used to foment segregation.

Fanshen

Cox, a writer, director and producer whose work has explored the

boundaries of race, says the debate misses a key point: “Race itself is a

lie,” created by the wealthy landed gentry in Europe to separate

themselves from the poor, ethnically diverse masses.

Rather,

she says, racial identity is an accumulation of experiences based on

culturally relevant social interactions with family, communities, and

the world writ large. It’s likely, Cox says, that Leo lacked those

experiences growing up, despite his ancestry.

“There’s

no blood test that can tell you you’re Black, she says. “The way you

receive it is by your community, by your parents, by your family, by the

stories they tell, by who you spend time with” — and who encourages

love of that identity.

For

example, “I am a Black woman with blonde hair and blue eyes who passes

as white,” Cox said. “I’ve experienced a lot of privilege for the way I

appear. But at the same time, I was raised by parents who insisted that

we understand our blackness and be proud of our blackness. [Leo] didn’t

get that.”

Power and representation

Nevertheless,

the debate over the pope’s racial identity matters because of what he

represents, and because Black people, historically marginalized, yearn

to see themselves in powerful, exclusive positions like the papacy.

“I

work in film and TV and media, and I know how incredibly important it

is for people to see themselves in many different roles,” and “that

directly leads them to knowing what they can do and be in life,” said

Cox. “To have a Black pope means [untold] millions of children who are

Black also know that this is something that is attainable in their

lives, and that’s important.”

Copeland,

the Boston University professor, agrees, adding that the debate “is a

reminder that race is ultimately about power and not appearance.”

Copeland

said that as leader of 1.4 billion Catholics worldwide, “If [Leo] was

to come out and publicly claim his [racial] ancestry, that would shift

the conversation immediately, vs. if he’s a little bit more colorblind

about it: ‘Well, yeah, that’s factual, but that’s not how I identify

myself. I identify as white.’ ”

By

contrast, Copeland added “let’s say he was to embrace that aspect of

himself. That would be deeply affirming for many, many people, and it

would potentially be a serious counter to people who have a racist

agenda or white nationalist agenda, who would want to claim him: ‘He’s

one of us. He’s a white American. You guys don’t get to claim this pope.

He’s our pope … he’s a white pope.”

Still, given the headlines, Leo may have to address the question sooner rather than later.

“I’d

actually be curious to see if he receives direct questions about that,

and how he reacts,” Copeland said. “I think how he responds to that

question could potentially shift the conversation dramatically.”

This article originally appeared on WordinBlack.com