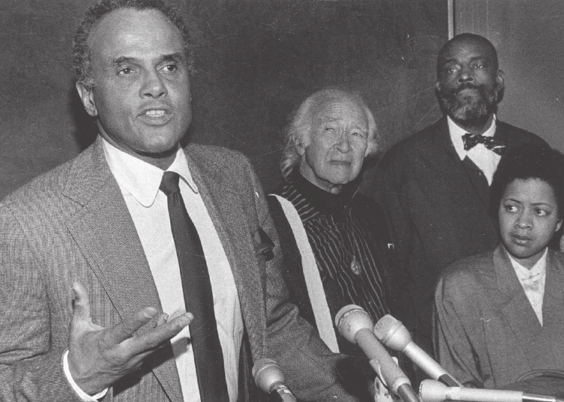

Harry Belafonte, George Wald, Mel King and Margaret Burnham.

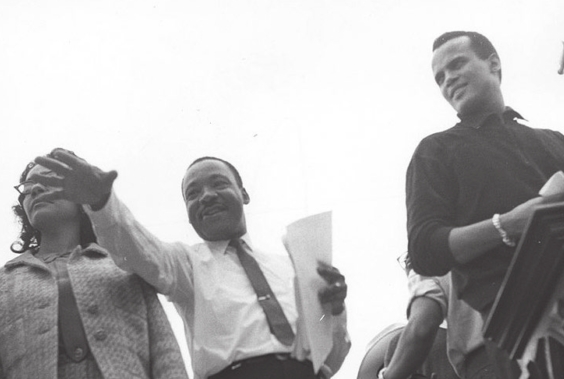

Martin Luther King, Jr. with Harry Belafonte in Montgomery, Ala., 1965.

Harry Belafonte and an 11-year-old Rwandan refugee girl, Akimane.

Powerful voice for change quieted at 96

Harry Belafonte, the son of West Indian immigrants who scaled artistic heights on concert stages and movie screens but was most devoted to human and civil rights advocacy, died last week at the age of 96 in his New York apartment.

The iconic singer and actor launched his career by bringing the sound of the Caribbean to American living rooms as the “King of Calypso” in the mid-1950s. His lithe grace, stunning smile and husky tenor voice soon landed him movie and television roles.

But the allure of public acclaim and the wealth afforded by performances on stage and screen mattered less to Belafonte than how he could leverage fame and money to serve the cause of equal rights and human dignity.

He put his career at risk by aligning himself closely with the civil rights movement in its nascent stages, making constant appearances at protests and quietly financing much of the organizational work led by his close friend Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who often stayed at Belafonte’s West End Avenue flat on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.

Belafonte later became closely identified with the battle against apartheid in South Africa, a cause that brought him to Boston numerous times, including the triumphant 1990 appearance of Nelson Mandela in the city shortly after his release from prison, having been incarcerated for 27 years.

“I

wasn’t an artist who’d become an activist,” wrote Belafonte in his 2011

memoir, “My Song.” “I was an activist who’d become an artist. Ever

since my mother had drummed it into me, I’d felt the need to fight

injustice whenever I saw it, in whatever way I could. Somehow my mother

had made me feel it was my job, my obligation. So I’d spoken up, and

done some marching, and then found my power in songs of protest, and

sorrow, and hope.”

In

Boston, Belafonte found equally committed partners among members of the

Free South Africa Movement, who hosted political leaders living in exile

and led protests against Deak-Perera in the financial district for

selling Kruggerands, gold coins produced by the apartheid regime. He

made frequent appearances at New England Circle discussion gatherings in

the 1980s hosted by the Dunfey family, owners of the Parker House, and

accompanied Mandela on his trip to Boston.

By

then, Belafonte’s celebrity role as a champion of folk and

working-class ballads — like his first hit, “The Banana Boat Song,”

better known as “Day-O” — had receded in the public mind, replaced with

images of the tall and slender singer and actor, with his distinctive

high forehead, café-aulait complexion, widow’s peak and flashing eyes at

the head of protest marches and sit-ins.

“Fearless

is the word I would use to describe him,” said publicist Colette

Phillips, who helped organize Mandela’s Boston appearances. “He was one

of very few celebrities who was actually willing to put his conviction

on the line even if it meant he would be blacklisted.”

Belafonte’s

relationship with King began with a phone call in 1956. He attended the

landmark March on Washington in 1963 and raised money to support King’s

family after his assassination in 1968. His work brought him close to

the Kennedy family and other prominent liberals in politics and society.

In

1964, during Freedom Summer, Bob Moses of Boston called Belafonte to

ask for money to finance the waves of students spreading across the

Mississippi Delta to register voters. Belafonte offered to wire the

money, but Moses just laughed. “They’ll never let us use a bank,” he

said, according to accounts from the time.

“You’ll have to bring it yourself.”

The

singer called his friend, the late Sydney Poitier, who had acted with

him in the Negro Ensemble Company in New York City in the 1940s, and

they flew to a small rural airport, climbed into a car and barely

escaped a Klan posse that pursued them on narrow country roads.

Belafonte

frequently lamented that few artists, especially today, put their

careers on the line to stand up for their beliefs, whether challenging

the images of Blacks on the screen or policies hurting the poor and the

marginalized.

“Back in

1959,” he told the New York Times in an interview, “I fully believed in

the civil rights movement. I had a personal commitment to it, and I had

my personal breakthroughs — I produced the first Black TV special, I

was the first Black to perform at the Waldorf Astoria. I felt if we

could just turn the nation around, things would fall into place.”

Accusing

modern celebrities of turning “their back on social responsibility,” he

said, “There’s no evidence that artists are of the same passion and of

the same kind or commitment of the artists of my time. The absence of

Black artists is felt very strongly because the most visible oppression

is in the Black community.”

Malia

Lazu, a Boston businesswoman and activist who worked for Belafonte on

social activism and grassroots organizing efforts for five years, said

he “always held our feet to the fire.”

“When

I first started working for him,” she said, “he told me that within two

months we were going to have a gathering of the young – 30,000 gang

members to come to a convention to make a pledge to peace and criminal

justice reform.”

Asked

how they’d pull that off, Belafonte smiled and calmly said, “Nelson

Mandela filled Yankee Stadium on one day’s notice. We’ll do it.” He

reportedly said the same thing when asked how he would pull together an

all-star cast of artists to perform the song “We Are the World” to

benefit famine relief in Africa.

Lawrence

Watson, a Boston singer who organized a concert for Belafonte when he

received an honorary degree from the Berklee School of Music, grew up in

the Eleanor Roosevelt projects in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood

of Brooklyn worshiping the singer.

“He

had the courage to speak about the situation he faced as a Black man in

America,” said Watson. “He inspired me. I had him and Paul Robeson and

Berry Gordy as role models.”

Born

as Harold George Bellanfanti Jr. in Harlem in 1927 to a father from

Martinique and a mother from Jamaica, he moved to Jamaica at age 9 to

live with relatives before returning to the U.S. four years later. He

attended George Washington High School in New York but dropped out in

1944 to enlist in the Navy.

Back

in New York after loading munitions by day and studying books by W.E.B.

DuBois and others recommended by Black shipmates by night, he acted on

the stage and sang in clubs. His breakthrough album, “Calypso,” came out

in 1956 and stayed atop the Billboard charts for 31 weeks.

He

became a leading attraction on concert stages throughout the U.S. and

Europe and by 1959 was the most highly paid Black performer in history.

He

starred with Dorothy Dandridge in a 1954 production of “Carmen Jones,”

and in 1957, his screen role with Joan Fontaine in “Island in the Sun”

suggested a romance with his co-actor, provoking outrage from

segregationists.

Belafonte later produced and appeared in other films, including Spike Lee’s “Black KKKlansman.”

“About

my own life, I have no complaints,” wrote Belafonte in his 2016

autobiography. “Yet the problems faced by most Americans of color seem

as dire and entrenched as they were half a century ago.”

Belafonte’s

first marriage came in 1948 to Marguerite Boyd, whom he met while

stationed in Virginia. They had two children, Adrienne Biesemeyer and

Shari Belafonte, who both survive him. He later married Julie Robinson,

the only white member of the Katherine Dunham Dance Troupe, and is

survived by their two children, Gina and David Belafonte. His third

marriage was to Pamela Frank, a photographer, in 2008.