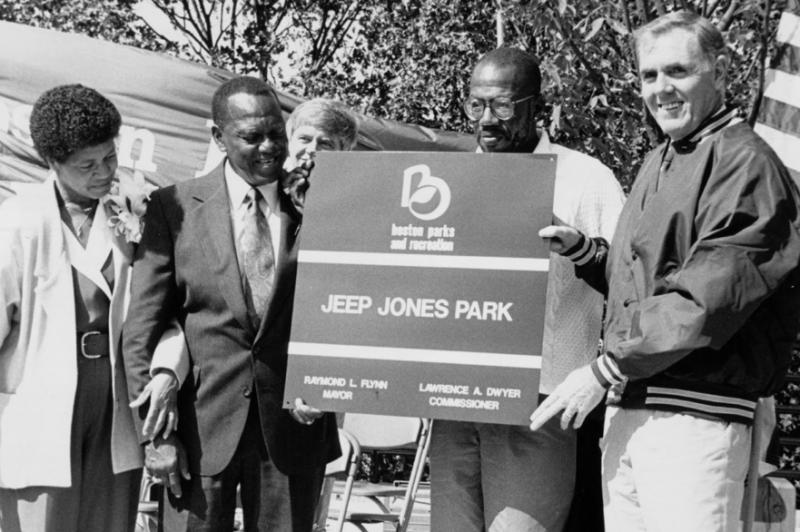

Community marks life of public service

Clarence Jack “Jeep” Jones Jr., Boston’s first and only black deputy mayor, died at age 86 on Feb. 1, the first day of Black History Month.

On Friday, mourners at the Twelfth Baptist Church in Roxbury, where he was a member for more than 50 years, remembered Jones for his vigilant work to keep the city calm during the turbulence of the busing era. Others recalled his guidance of the Hub’s powerful development agency during his 32 years on the board, 24 of them as chairman.

And some, like his daughter Meta Jones, remembered more private moments, like a monthlong cross-country trip in a Winnebago with his eight children in the summer of 1977. “We will always treasure that memory,” said Jones. “He took us to the Grand Canyon and Universal Studios in California. We were in Memphis when Elvis died. And as we passed through cities in the South, he told us what it was like for black folks there back in the day.”

Though

Jones did his best to shield his family from the stress and strain of

his demanding job, Meta Jones recalled a friend telling her in April

1976 that she thought her father had been assaulted by a flag-wielding

demonstrator on City Hall Plaza. “I was terrified to hear that and so

relieved to learn he hadn’t been the one attacked,” she said.

In

fact, according to his longtime aide Clyde Thomas, Jones had witnessed

the assault on attorney Ted Landsmark by anti-busing protester Joseph

Rakes from a window at City Hall and rushed downstairs to comfort

Landsmark before EMTs arrived. The Pulitzer Prize-winning photo of the

attack endures as a lasting image of the hostilities unleashed by the

crosstown busing plan, which Jones — who was installed as deputy mayor

just weeks before Old Glory was wielded as a spear — was enlisted to

dampen.

“Word had

gotten out that Kevin White was going to appoint a black individual to

serve as part of his cabinet,” said Thomas. “And so a number of

prominent minorities began applying for the job. But some people,

especially Rev. Michael Haynes, supported Jeep.”

The

backing of the late Twelfth Baptist Church minister, former state

representative and colleague of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., proved

crucial in White’s choice. “It was a tough job,” added Thomas. “He

worked the streets and the policy suites, he had liaisons with the

police department and helped lead the mayor’s task force on busing, and

he went out to countless meetings in the neighborhoods as the face of

the administration. If he ever wanted to leave, he never shared that. He

was a religious man and used to pray in his office.”

In 1981, White appointed Jones to

the Boston Redevelopment Authority board, where over the next three

decades he helped shape the skyline of Boston and oversaw efforts to

spread the benefits of downtown development to the neighborhoods. Among

his allies was a fellow veteran of Mayor White’s political machine,

Boston City Councilor Bruce Bolling. Joyce Ferriabough, wife of the late

councilor, said her husband, as the only African American in the

nine-member city council elected in 1981, took over from Jones much of

the constituency and advocacy work he had done in City Hall.

Ferriabough,

after attending the overflow funeral for Jones at the historic Warren

Street church, said Jones should be counted among the most influential

leaders of Boston’s black community.

“Like

Chuck Turner, Melnea Cass, Robert Coard, Bruce and Royal Bolling, Mike

Haynes, the Guscott brothers and so many others,” she said, “we will

always stand on their shoulders.”

Jones’

death and the recent passing of Haynes left Roxbury without two of its

pillars of church and state, noted the Rev. Jeffrey Brown, associate

pastor of the Twelfth Baptist Church. “Jeep Jones’ name and work are

synonymous with the uplift of Roxbury and progress in Boston,” said

Brown.

“I was blessed

to drink regularly from his deep spiritual reservoir of faith. He was

part of the church’s ‘Friday Community Walkers.’ Along with Pastor

Arthur Gerald, he would walk Warren Gardens and all through Dudley into

the evening, greeting residents and listening to concerns, for years,

well into his 80s.”

Born

in Roxbury, Jones was known as “Junior” but later acquired the nickname

“Jeep” after a dog who followed him around the neighborhood. He

attended Boston Public Schools and graduated from Winston-Salem

University in 1955, excelling in sports and helping to win a basketball

championship for the historically black college.

Along

with Haynes, Jones in the 1950s formed a mentors program at the Norfolk

Settlement House in Roxbury called the Exquisites. The program taught

high schoolers to play basketball and also exposed them to etiquette and

how to navigate social situations and job interviews. “It was a

blessing for the young men to learn social skills and the importance of

academics and good sportsmanship and not just the game of basketball,”

said a statement from the Jones family.

Jones

joined the U.S. Army during the Korean War and served in Germany as a

medic. Returning to Boston, he taught school, worked as a probation

officer, and directed Mayor White’s Youth Opportunities Program and his

Youth Activities Commission. White later appointed Jones as director of

the Office of Human Rights, where he pushed for increased minority

hiring in the police and fire departments and city agencies.

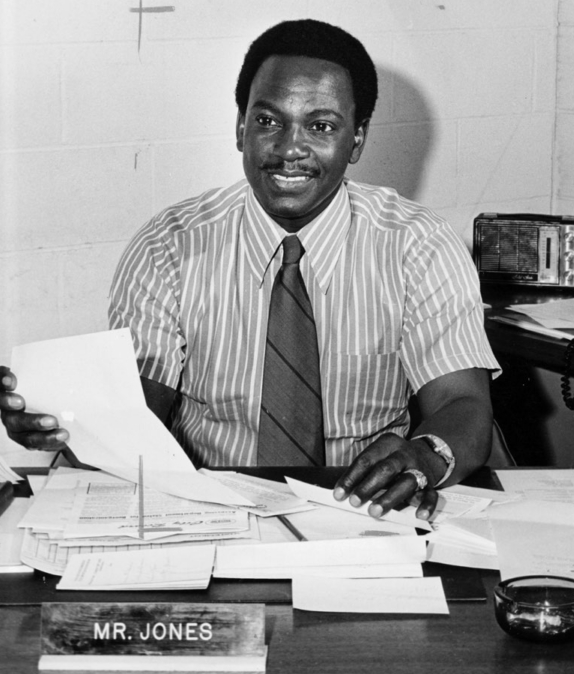

Named

as White’s deputy mayor in March 1976, he spent five years in the post

before his appointment to the BRA. Boston City Councilor Michael

Flaherty’s first job was at the agency, and he remembered Jones’

kindnesses to him and his strong leadership. “Jeep left a lasting mark

on me and on Boston and did so with grace and dignity,” he said.

Always close to the Twelfth Baptist Church, Jones served as a trustee, deacon, Sunday school teacher and usher.

Jones

is survived by Wanda Hale Jones, whom he married in 1983; three

daughters, Meta Jones, Melissa Elow and Nadine Jones; four sons, Kenneth

Cunningham, Michael Jones, Mark Jones and Mark Cunningham; a sister,

Jacqueline Hoard; 15 grandchildren; and four great-grandchildren.