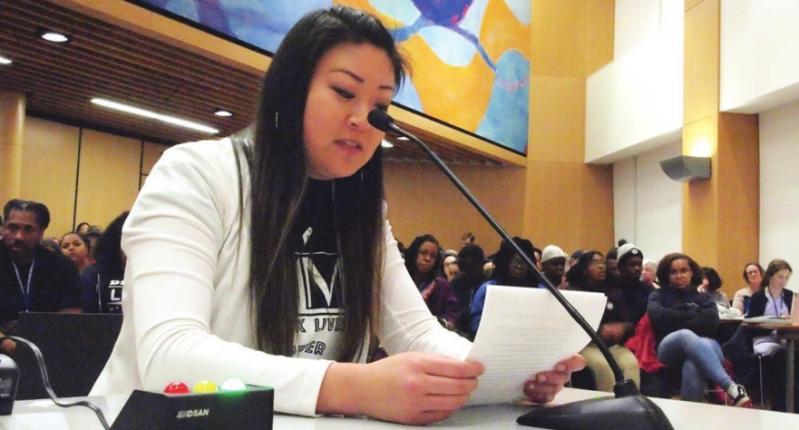

Boston Teachers Union President Jessica Tang, wearing a Black Lives Matter tee-shirt, addresses the Boston School Committee.

Police union letter draws civil rights groups’ ire

A police union official had angry words for the Boston Teachers Union’s third annual week-long Black Lives Matter observance, firing off a broadside at BTU President Jessica Tang.

In his letter to Tang, Boston Police Patrolmen’s Union President Michael Leary said the activities of the national Black Lives Matter Movement, which formed in response to police shootings of unarmed blacks, “have the effect of making my members less safe.”

“Policing has always been a dangerous profession, but groups like Black Lives Matter, by inaccurately demonizing police as racists who kill innocent people, have made policing more dangerous than ever before,” Leary wrote in the letter, dated Monday, Feb. 3.

Leary’s letter drew a sharp rebuke from the NAACP Boston Branch and the Massachusetts Association of Minority Law Enforcement Officials, who issued a joint letter Wednesday.

“There

are many police officers who understand the ideals and values behind

BLM and align themselves with BLM and other social justice

organizations,” the letter reads. “We do not believe BLM is synonymous

with ‘anti-police.’ In fact, we believe that BLM is a reflection of the

historical mistreatment of black and brown people in this country, not

only by law enforcement but also by a culture that has quietly

undermined the value of the lives of black and brown people.”

The joint letter acknowledged that some MAMLEO members took exception to the BTU demand to “fund counselors, not cops.”

Tang

and others, however, testified at the School Committee meeting

Wednesday in favor of increasing funding for mental health counselors in

the schools rather than having police officers intervene in

school-related discipline issues.

“We

believe counselors need to be a higher funding priority over

theoretically increasing the number of police in schools,” Tang told

School Committee members. “With limited budgets and cuts we believe

adequate access to social-emotional well-being, restorative practices

and other efforts are more effective than increasing police presence in

our schools.”

Tang

joined dozens of teachers and students from BPS schools at the School

Committee meeting who wore Black Lives Matter teeshirts. While not

affiliated with the national Black Lives Matter movement, the local

effort is part of a national movement of teachers advocating against

policies they say harm black children. The movement started in Seattle

four years ago. This year is the third in which Boston teachers have

taken part in the observance.

During

the School Committee meeting, Tang and others framed the Black Lives

Matter observance in the context of their demands for more resources for

BPS students.

“Although

it’s important to celebrate black history every month, the month of

February is an opportunity to elevate and highlight the work that we’re

doing in this district when it comes to affirming black lives and

nurturing black futures in the Boston Public Schools,” Tang said. “And,

of course, a baseline budget is a part of that.”

Teachers

testified in favor of adding ethnic studies into the BPS curriculum;

ending zero tolerance policies that they said disproportionately target

black children for out-of-school suspensions; and ending the

department’s practice of sharing student information with Boston Police

Department officials, who between 2014 and 2017 made accessible to

federal immigration officials information on more than 100 students,

resulting in at least one deportation.

“There are undocumented students in our communities whose safety is at risk,” said Boston Latin Academy student Khymani James.

Tang

spoke in support of BPS hiring more teachers of color, noting that the

district is still under a court order to diversify its majority-white

teaching staff.

“We have a court mandate,” she said. “We need to reach that goal.”

Speaking

outside the School Committee meeting room, Joel Richards, who teaches

technology at Blackstone Elementary School, told the Banner he felt

compelled to participate in the BTU initiative.

“Silence isn’t an option for black people or people of color,” he said.

Richards

recalled an incident a few years back when he taught at Mattahunt

Elementary School. Leaving the school one day dressed in a shirt and

tie, he was stopped by an officer who asked for his ID and questioned

him.

Upset, Richards said, he asked the officer how he would feel if he were accosted while leaving work.

“He just said, ‘Well, I didn’t put you on the ground.’”