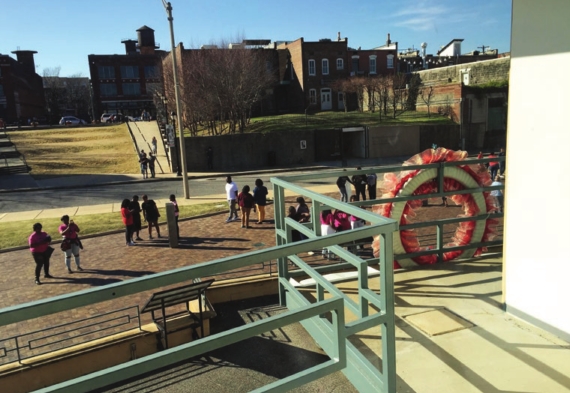

The view from the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, now part of the National Civil Rights Museum, shows the balcony where King was standing when he was assassinated in 1968.

Workers repaint inscriptions at the Martin Luther King Jr. Center in Atlanta.

The

burial vault of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King is

covered during renovations at the King Center in Atlanta in 2018.

ATLANTA — In 2018, the tomb holding Martin Luther King Jr. was covered in plastic while workers spruced up the reflecting pool that surrounds it. Written in the tiles is King’s promise that he will never be satisfied “until justice rolls down like water and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

King rests in the King Center, less than a block from the house where he was born, and just steps from the Ebenezer Baptist Church, where he — along with his father and his grandfather before him — preached. All are part of the Martin Luther King Historic District, which was again ready for the spotlight on April 4, 2018, the 50th anniversary of King’s assassination.

The year 2018 was a year of grim 50th anniversaries, because 1968 was an especially dark year. It was a year marked by war, riots and assassinations, by deep divisions and the death of dreams. No event shook the nation like King’s death in Memphis.

King had come to Memphis in the spring of 1968 to march in support of sanitation workers. The nearly all-black workforce had gone on strike after two workers were killed by a trash compacting machine. They did dangerous work for pitifully low pay. The placards they carried demanded not just pay, but dignity. “I AM A MAN,” they declared.

King was standing on the balcony outside his room at the Lorraine Motel, talking with friends in the parking lot below, when the

shots rang out. The motel is now part of the National Civil Rights Museum. Visitors can look through a window into the room where King stayed, unchanged since his death, and look out past the balcony to the rear window of a rooming house where James Earl Ray stood when he fired the shots that killed the conscience of a nation.

When it was first proclaimed in 1976, Black History Month made sense. The stories of the struggles and achievements of African-Americans had gone untold for so long, why not encourage people, especially students, to learn about Harriet Tubman, Booker T. Washington, Frederick Douglass and, of course, Martin Luther King?

But segregating African-American history from American history — giving them the shortest month on the calendar, at that — has always felt not quite right. Those stories aren’t black history; they are American history, part of a huge canvass of aspirations, conflict and connections. Their stories need to be included in our story, not stored on a separate-but-equal shelf.

That context is being provided where people meet history faceto-face. There’s the small stone stump on a corner in Fredericksburg, Virginia, that a plaque identifies as the main auction block for slave sales, or the sign in New Orleans marking the location of the notorious slave pen featured in “Twelve Years a Slave.”

You can’t miss Charleston’s Old Slave Mart, now a museum operated by the city. And if you’re driving

down Rte. 80 in Alabama, you’re reminded every few miles of the march

King led from Selma to Montgomery that inspired passage of the 1965

Voting Rights Act.

Some

of the changes are subtle. At Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, curators

avoid the term “slaves,” preferring the terms “enslaved men and women,”

or “enslaved families.” It makes them more human by describing slavery

as their condition, not their identity.

One

of the ways Memphis honored Dr. King was by removing the statues of two

Confederate leaders. City leaders did it quickly over the December

holidays, taking advantage of a loophole in a state law enacted to

prevent such assaults on Confederate memorials. Some conservatives

believe in local decision-making right up to the point local people make

a decision they disapprove of.

I’m

fine with Memphis’ decision. The statue of Confederate President

Jefferson Davis, erected in 1964, was more a rejection of the Civil

Rights Act than a tribute to the Civil War. But the National Civil

Rights Museum teaches a lot more history to a lot more people than the

relocation of a dated and offensive statue.

The

granddaddy of Confederate monuments sits outside Atlanta, where Robert

E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson and Jefferson Davis are carved into Stone

Mountain, the site where the second iteration of the Ku Klux Klan was

founded. A Democrat running for governor has called for the figures to

be sandblasted off the face of the mountain, which seems unwise as well

as unlikely.

In his

famous speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, King said he dreamed

of a time when America would, “Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of

Georgia.” On the anniversary of King’s death, one Georgia legislator

hoped to see thousands of people on top of Stone Mountain. Another has

called for a “freedom bell” to be built atop Stone Mountain in honor of

King.

Sounds good to me. Doing history right is a matter of addition, not subtraction.

Rick Holmes can be reached at [email protected]. You can follow his journey at www.rickholmes.net. This article was written in 2018 for the 50th anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King’s death.