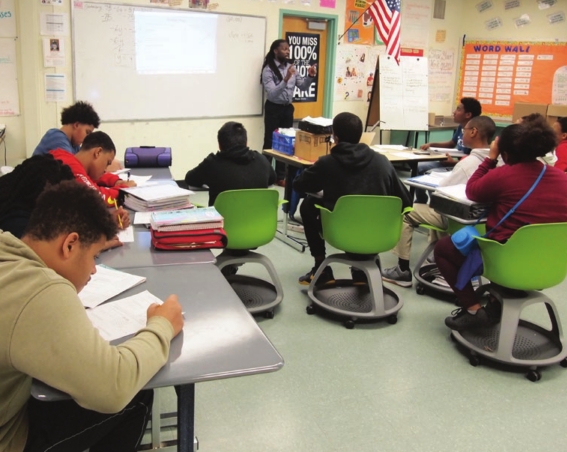

Students in an eighth-grade English Language Arts class in a group discussion at the Joseph Lee school in Dorchester.

Students can choose to sit in movable chairs, use standing or traditional desks in some classrooms at the Joseph Lee school.

Flexible seating for new instructional methods

Each student in Elizabeth Di- Franco’s eighth-grade English language arts room at the Joseph Lee school has been assigned a number one through four at the beginning of class. As DiFranco faces the jumble of students seated at wheeled desks, she orders them into groups.

“If you’re a one, roll together, if you’re a two, roll together, if you’re a three roll together,” she says, as the students scoot their seats into clusters to begin group discussions. The movement looks a bit like bumper cars, but in less than a minute the clusters are well-formed.

“In a traditional classroom, you’ve have to get up and move through rows,” DiFranco tells reporters visiting her classroom. “They would be climbing over each other.”

The new desks — green molded plastic chairs with desktops that swivel to either side to accommodate left- and right-handed students, were purchased as part of the Boston Public Schools’ 21st-century furniture initiative, aimed at facilitating new modes of instruction.

“In today’s way of teaching, you have flexible grouping and abilities grouping,” says Principal Kimberly Crowley. “You can choose the way you want to learn.”

“A lot of our focus is on groups and project-based learning,” Di- Franco added. “This furniture lends itself to that.”

The

furniture was delivered before the beginning of the school year and

enabled teachers in 11 of the school’s 41 classrooms to upgrade with

pieces such as inflatable ball chairs, reading nooks, wheeled monitors,

standing desks and other furniture designed to accommodate students’

preferences.

In all,

BPS made available $13 million for its 125 schools to purchase new

furniture, with allocations to individual schools calibrated according

to factors including school populations and the numbers of students with

special needs. The Lee school’s $130,000 allocation helped them acquire

650 pieces of furniture.

Pushback

Not

all teachers who received the new furniture were happy with it. On the

BPS Facebook page, the district’s posting about the new furniture

unleashed a torrent of complaints.

“I

am really disappointed in the quality and safety of the new furniture,”

Amanda Benson, an English as a second language teacher at the P.A. Shaw

school told the Banner. “Among the items I received were yoga ball

chairs. They are low quality and don’t look like they will last the

school year. I also got stools that allow students to tilt and rock.

However, they are top heavy and were constantly tipping over. I chose to

remove them from my classroom, as I was concerned for student safety.”

At

Boston Latin Academy, teacher Michael Maguire was a member of a team of

staff who made decisions on what to purchase for the school. The

furniture was delivered by September of 2018, and within weeks, Maguire

says, he and other teachers began noticing that some of the items were

of poor quality.

Like other teachers, Maguire told the Banner that the $80 stability balls available through the BPS vendor rapidly deflated.

“For the most part, they deflated within weeks,” he said. “Each ball cost $80. They don’t cost that much in retail stores.”

Other

items that gave teachers pause, Maguire said, included $2,000 60-inch

monitors mounted on wheeled bases and standing desks that cost $850.

BPS

Chief Operations Officer John Hanlon said schools were able to choose

furniture from among six vendors who went through the district’s

competitive bidding process. Although the costs of some items may seem

high, especially for teachers who are used to digging in their own

pockets to outfit their classrooms, Hanlon noted that the vendors

selected by BPS were required to supply furniture that meets stringent

safety codes.

Another

advantage of the public procurement process is that BPS was able to

extract volume discounts from the vendors, Hanlon added.

He acknowledged that some teachers may have been dissatisfied with their schools’ purchases.

“When

you have 50,000 items of furniture among the district’s 125 schools,

you’re going to have some people who are not happy. It’s to be expected

when you have a process of this scale affecting this many people.”

Collaborative decisions

Each

school set up committees of teachers and members of the school site

councils that selected the furniture the schools purchased. At the Lee

school, the 12-person council prioritized classrooms with high numbers

of special needs students who would benefit from furniture that

accommodates their needs.

In

Kwame Sarto Mensah’s eighthgrade math class, students with poor vision

and no glasses can roll closer to whichever of the two whiteboards in

the classroom he’s using.

“Everybody in the back, roll on up if you can’t see,” he tells the students.

Some in his classroom use the rolling chairs, while others are seated at traditional desks with larger work surfaces.

Hanlon

said principals at schools he’s visited since the beginning of the

school year have expressed satisfaction with their purchases.

“To a person, every school leader I talked to was excited about what this has enabled them to do in the classroom,” he said.

The

21st-century furniture initiative is part of the district’s BuildBPS

program aimed at constructing new school buildings and renovating

existing ones. Although the $1 billion allocated in the city’s capital

budget can only fund reconstruction or renovation for a fraction of the

district’s 125 schools, the furniture initiative can reach into every

building.

“This is one

of the cornerstone, system-wide initiatives we’ve put in place to make

sure every school benefits from BuildBPS,” Hanlon said. “It’s breeding a

new sense of excitement in classrooms across the city. This is the

first time we’ve ever done something like this.”