More radical ideas ignored as efforts to memorialize King went mainstream

When Martin Luther King, Jr. was felled by an assassin’s bullet 50 years ago, the news of his death shook the nation.

In

the immediate aftermath of the April 4, 1968 murder, violence broke out

in 125 American cities, leading to 48 deaths, more than 1,600 injuries,

extensive property damage and more than 10,000 arrests. The federal

government deployed 57,000 soldiers and National Guardsmen to quell the

unrest, the largest force ever deployed for a civil emergency in U.S.

history.

While the

initial reactions were violent, King’s death left a legacy of positive

change in the United States that, while falling short of his lofty aims

to build a more just and equitable society, nevertheless had profound

impacts on the lives of people of color. As the gains of the civil

rights movement in housing, employment and public accommodation

solidified in the 1970s, King’s ideas and calls for a nation free of

prejudice became more widely accepted.

But

not all his ideas. Some aspects of King’s legacy remained controversial

in American politics — in particular, his anti-war stance and his calls

for trans-racial anti-poverty and labor movements.

King, the radical

In

the months leading up to his death King was outspoken in his opposition

to the war in Vietnam and drew fire from critics with his calls for

demonstrations against poverty in the nation’s capital. As part of his

Poor People’s Campaign, King had planned to create a poor people’s

encampment later in April on the 15-block Washington Mall to demand that

Congress act to take action on anti-poverty and civil rights

initiatives.

King told

reporters he was willing to risk being arrested to lead the

demonstrations, which had the endorsement of the American Federation of

Teachers, the AFL- CIO major civil rights groups and organizations

representing Puerto Ricans, Mexicans and Appalachian whites. The planned

demonstrations underscored growing dissatisfaction with the Johnson

administration’s War on Poverty and pressed for race-neutral policies,

including King’s call for a national basic income.

King’s assassination

quickly derailed the Poor People’s Campaign, taking with it the

activists’ best chance at a broad-based, multi-racial movement. But in

the months and years that followed, there were increased responses to

the conditions in which blacks lived — the issues that had provided the

impetus of the Civil Rights Movement.

Initial response

In

the immediate aftermath of his assassination, King’s image in the

popular consciousness began to change. His legacy became less about the

the Poor People’s Campaign and the controversial anti-war stance that,

more than anything else, put him in the crosshairs of J. Edgar Hoover’s

FBI, and more about the heart of the civil rights movement — its call

for black equality.

Georgetown

University Sociology professor and author Michael Eric Dyson argues

that at the time of King’s death, many whites celebrated his passing.

King’s image, Dyson argues, has been sanitized with time.

“His

danger has been sweetened,” Dyson told National Public Radio in a 2008

interview. “His threat has been removed. There are only smiles and

whispers and applause now without the kind of threat that he

represented.”

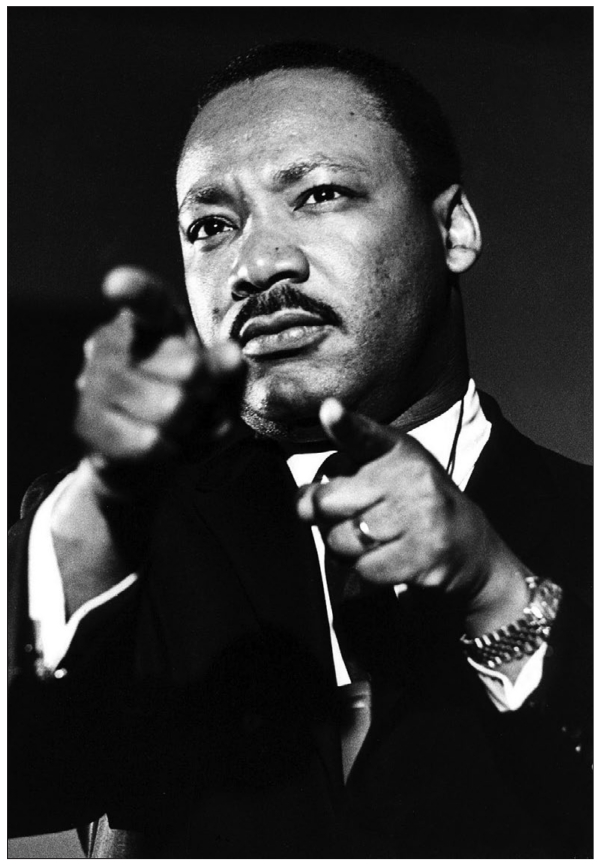

Martin

Luther King’s legacy of activism around labor rights and the war in

Vietnam has taken a back seat to his calls for racial unity.

King with President Lyndon Johnson as he signs civil rights legislation into law.

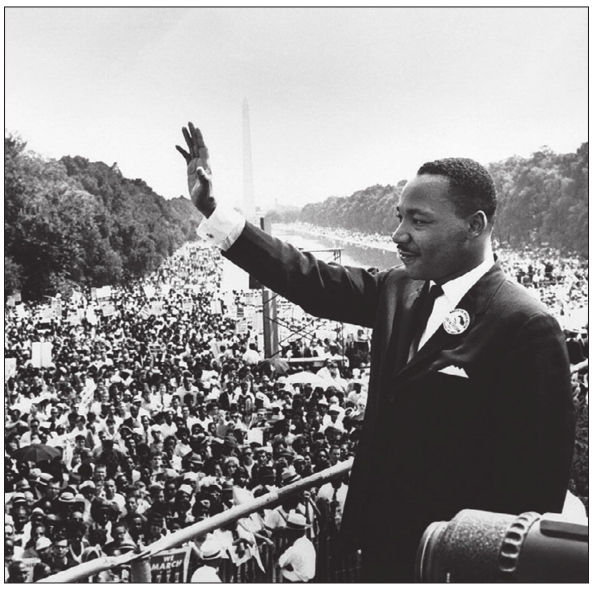

Martin Luther King during the historic March on Washington.

Thus,

King’s “I have a dream” speech — which he delivered at the 1963 March

on Washington — came to symbolize King in America’s popular

consciousness. His anti-war, pro-labor stands from the latter half of

the decades, while not erased from history, receded to the background.

Yet

even with the sanitized version of King that emerged in the years after

his death, the near-universal acceptance of King and his civil rights

legacy seen in the United States today took more than three decades to

cement.

The King holiday

Boston

was an early adopter of an annual holiday honoring King. In 1970, the

then all-white City Council voted in favor of the official holiday, with

South Boston Councilor Louise Day Hicks casting the sole dissenting

vote. While city and state workers did not have a day off, Boston Public

School students did, and 34 Boston businesses, agencies and community

schools agreed to close on Jan. 15 as well.

King’s

birthday did not become a national holiday until 1983 — after nearly 15

years of advocacy by civil rights activists. Much of the initial

resistance to the King holiday centered on his ties to communists and

his opposition to the Vietnam war.

Massachusetts

Sen. Edward Brooke and Michigan Rep. John Conyers first introduced the

bill authorizing the holiday in 1979, but it fell five votes short with

congressional representatives arguing that U.S. holidays should not be

designated for private citizens who never held elective office.

Supporters

collected 6 million signatures in support of the holiday in 1980 — the

largest petition drive in U.S. history. U.S. Sen.

Jesse

Helms of North Carolina led opposition, submitting a 300- page document

detailing what he said was evidence of King’s ties to communists. U.S.

Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York threw Helms’ papers on the

floor of the Senate, stomped on it and called it a “packet of filth.”

The

bill passed the U.S. House of Representatives 338 to 90 later that year

and Ronald Reagan signed it into law. Although the day became a federal

holiday, several U.S. states declined to observe the day. In 1990, the

National Football League moved Super Bowl XXVII from Arizona to

California to protest the state’s refusal to adopt the holiday. Two

years later, voters in Arizona passed a statewide referendum to observe

the day. In 1991, New Hampshire created a “Civil Rights Day” holiday to

mark King’s birthday. South Carolina, the last holdout, marked King’s

birthday in 2000, a few months after Utah had moved to do so.