FAST TRAINS

continued from page 11

trains dart passengers between destinations at around 200 miles per hour. Here in the U.S., other states are also thinking bigger than Illinois. California is currently batting around the idea of a frictionless magnetic-levitation system between Los Angeles and Las Vegas similar to China’s.

High-speed rail’s critics argue against sinking billions in taxpayer money into Amtrak, which hasn’t recorded a profit in any year since its inception in 1971, and relies on dated fossil-fuel burning technology.

Bill Warren, an emeritus professor of environmental studies at the University of Illinois at Springfield puts it another way. Warren explains that in 1940, the fastest train from St. Louis to Chicago took four hours and fifty-two minutes; today, the same trip takes five-hours-twenty-five minutes on Amtrak.

“So in 69 years we’ve gotten 30 minutes slower,” says Warren, who also taught trans portation planning at UIS. “The rest of the world has left us in their dust. It’s sad but true, but that’s the status of what we might call high-speed rail.”

Anyone in Springfield who’s ever booked passage with the dodgy Amtrak service or found themselves trapped at a railroad crossing as a hulking freight train ambled through town would likely be delighted with any increase in timeliness, no matter how small.

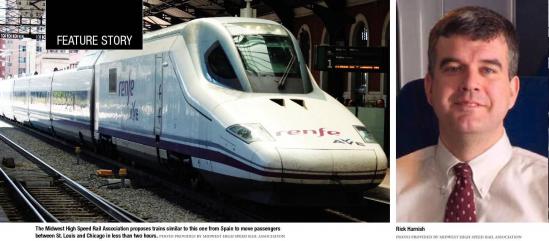

Whether it’s worth the expense is another question. Rick Harnish, executive director of the Midwest High-Speed Rail Association, leads the effort in Illinois and surrounding states to improve inner-city light-rail systems such as Chicago’s El and St. Louis’ MetroLink, streamline rail freight, and ultimately make high-speed rail a reality. He understands that taxpayers may need a little more speed for their money.

Separate from the state’s plan, Harnish’s association this week unveiled a proposal for a 220 mile-per-hour rail line through the Springfield corridor with — are you ready for this? — travel time from Springfield to Chicago of an hour and fifteen minutes. The St. Louis-Chicago trip would take one hour and fifty-two minutes.

“There are a lot of people who really want to figure out how to get St. Louis just two hours away from Chicago and it’s not because they want to do high-speed rail. It’s because they want to be two hours away from Chicago and high-speed rail is the only way to do it,” says Harnish.

“So that means people are traveling back and forth more frequently. That means they’re being more innovative, more productive,” he explains of the St. Louis to Chicago system. “What happens is that you turn these two cities that used to be economic rivals into two cities that work closely together.”

Limiting the commute to two hours would enable someone in St. Louis or Chicago to spend a full day in the city but still be home for supper. Connecting the two towns would also strengthen other local transit agencies as well as attract businesses to the Midwest, he adds. Harnish, who lives in Chicago and travels almost exclusively by train, characterizes the