Springfield promises to help the homeless

GOVERNMENT

Last July 22, nearly 20 public officials and social service agency providers gathered in a conference room at Scheels, the sporting goods store with a big aquarium, to talk about the homeless.

It was a special board meeting of the Heartland Continuum of Care, a consortium of public and private agencies required by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to serve as a money conduit. Hundreds of such continuums of care exist nationwide – they are funnels through which federal dollars flow to agencies tasked with preventing and eliminating homelessness, everything from emergency shelters to apartments to personnel who keep track of numbers. The idea behind continuums is to increase efficiencies, effectiveness and synergies.

There are 20 continuums of care in Illinois.

And Springfield’s continuum of care, for years, has ranked dead last in getting federal grants for the homeless. In 2019, the Heartland Continuum of Care, which covers Springfield as well as Menard, Logan and Mason counties, landed $402,569 for an area with nearly 252,000 people. Decatur and Macon County, with a population of less than 106,000, received $826,839. While other continuums have seen increases in federal funding, HUD grants for the homeless in Springfield have dropped by nearly $50,000 since 2015.

The July meeting was called two days after plans for a homeless center on 11th Street were unveiled in the State Journal-Register. Both the proposed center and the need for HUD money were on the agenda. The continuum that’s supposed to coordinate efforts hadn’t always been in sync with the city. Just six months earlier, board member Erica Smith, executive director of the Helping Hands shelter, had told colleagues that homeless people had told her that the mayor had informed them that a new shelter would open within a few months. “Helping Hands and other agencies involved with sheltering the homeless were unaware of these plans,” meeting minutes state. “The mayor also has announced that the city will be designating $250,000 per year over the next five years to deal with the issues of the homeless. No one on the (continuum) board was aware of this plan.”

The mayor’s promised shelter hadn’t materialized, nor had a day center that Langfelder had said was a priority more than a year earlier. For months, the continuum had discussed hiring a coordinator who would apply for grants so overburdened agencies wouldn’t have to sweat paperwork. Langfelder and Sangamon County Board Chairman Andy Van Meter came to the July meeting to talk about getting a coordinator and, beyond that, the larger issue of dealing with a burgeoning homeless population.

Meeting minutes suggest disarray and disagreement.

Van Meter said the county was willing to pay for a coordinator and likely would contribute six figures a year to address homeless issues, but a study was due. While a study aimed at measuring the homeless problem and developing options might take as long as a year, Van Meter said research was needed to identify issues and the best solutions.

Langfelder balked: What would a study entail? He said that he didn’t want to delay the proposed 11th Street center while a study was completed. Angela Bertoni, executive director of Sojourn Shelter, said there wasn’t time for a study, according to meeting minutes. Smith thought a study worthwhile – better to have a strategy, she said, than react to unfolding events.

The

private sector weighed in, with John Kelker, president of United Way of

Central Illinois, suggesting that a study be funded by the county, city

and private sector. John Stremsterfer, president and chief executive

officer of the Community Foundation for the Land of Lincoln, said his

organization would help.

The meeting adjourned without final decisions. It wasn’t long before efforts to help the homeless disintegrated.

Politics and promises

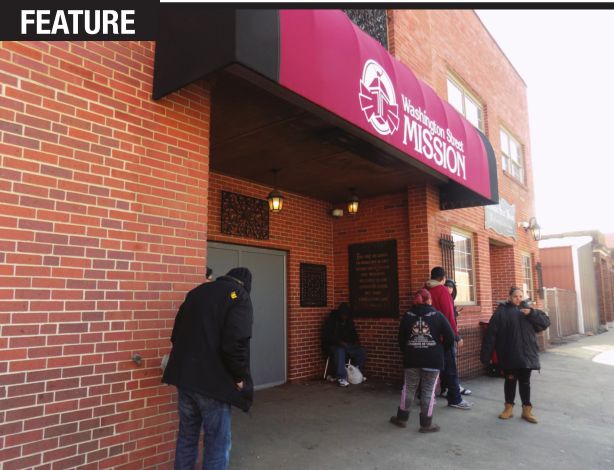

Those

who would aid Springfield’s homeless have searched for a shelter since

at least 2005, when the Salvation Army proposed one on J. David Jones

Parkway near Oak Ridge Cemetery. The city council said no.

A

2006 idea to put the Salvation Army’s shelter in the former county

health department on the 1400 block of East Jefferson died in the face

of community opposition before it became a formal proposal. In 2013, the

city council, facing angry neighbors, rejected a proposal by Helping

Hands to establish a shelter on North Fourth Street in a vacant building

last occupied by the Ace Sign Co. In 2015, the Salvation Army announced

plans for a shelter on Ninth Street with the help of more than $1

million in public tax increment financing money, which is supposed to be

used for economic development. After architectural and construction

contracts had been signed, Langfelder scuttled the shelter less than a

year later and engineered a move to the vacated Gold’s Gym on Clearlake

Avenue. Neighbors protested, and the Salvation Army surrendered. The

former Gold’s Gym is now a community center, owned and operated by the

Salvation Army.

The

130-bed homeless center on 11 th Street announced last July was supposed

to be more than just a sleep-and-leave shelter. Rather, the center,

with the help of Memorial Health System and Southern Illinois University

School of Medicine, would offer mental health services and other

medical care. It took more than a year to put together a coalition of

public and private service providers and find a site. Planners mulled a

detox center as well as space for people battling drugs or alcohol to

spend their first week or so of sobriety. The center, backers said,

would steer the homeless to social service agencies throughout the

community and serve as a starting point to getting people into permanent

housing scattered throughout the city. Homelessness would decrease by

addressing underlying issues resulting in lives on the street.

The

city council approved the center despite protests from neighbors and

the Springfield chapter of the National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People.

But

the proposal died after Langfelder, whose staff had helped pick the

building, started asking questions about the location. City support was

key. The mayor had promised $250,000 annually in federal block grants to

help pay for the project. While there was little opposition to the

concept, the site across the street from a Head Start school and in a

black neighborhood invited accusations of racism and concerns about

keeping kids safe. Project backers and aldermen accused the mayor of

poor leadership for helping create the project, then backing away at the

last minute. Nearly six months later, no alternative site has been

identified.

The

mayor’s resistance to a study seems to have softened since the Scheels

summit last July, when Langfelder questioned the need for the analysis

pushed by Van Meter and endorsed by United Way and the community

foundation. “Really, it was the continuum of care that expressed their

concerns: What’s the plan as it moves forward?” Langfelder said during a

Feb. 25 interview when asked his stance on a study. “They’re the

experts. They’ve been at it for a long time.”

Two

days later, the United Way issued a request for proposals aimed at

finding a consultant to perform a study and develop a plan. With no

price tag attached, the list of funders for the study includes the city,

the county, the United Way, the community foundation, Memorial Health

System, SIU School of Medicine and St. John’s Hospital. A contract is

due for award on May 29, with the winner expected to interview 75

interest groups ranging from the fire department to HUD to the homeless

to the NAACP to judges to neighborhood associations to churches. There

will be at least one public meeting. The continuum expects to hire a

coordinator soon. The contract position will be funded with $15,000 from

the feds, a like amount from the city and $40,000 in private money from

the Ford and Sommer family foundations. Kelker says he believes any

resistance to a study by the city and social service providers has eased

with funding for a coordinator tasked with landing grants.

“I

am a strong believer, that, when you get more people around the table,

it means your end results are going to be better, and it’s going to

create better transparency,” Kelker says. “We need to bring the

community together.”

Brian

McFadden, Sangamon County administrator, says the county’s concern

about homelessness blossomed after county officials went to Washington,

D.C., last June and met with officials with the Department of Housing

and Urban Development. The trip to the nation’s capital included civic

leaders and city leaders, McFadden says, an annual journey made to talk

to federal agencies about a variety of concerns. HUD, he says was blunt.

“They considered us the worst-performing continuum in the state,”

McFadden recalls.

The

continuum includes both public and private agencies. Players in the

homeless game do well when it comes to providing shelter and food so

folks don’t freeze or starve, McFadden says, but more is needed. “We

have a lot of plays, but we don’t have a playbook,” he says. “We want a

strategic plan, a comprehensive, communitywide, staged plan that

addresses all aspects of the homeless.”

If

a plan sounds familiar, it should. In 2003, Mayor Tim Davlin convened a

25-member task force that issued a report aimed at ending homelessness

in Springfield within a decade. “If you have no plan, you have nowhere

to go,” Davlin said when the report and strategy was unveiled at the

mayor’s 2004 prayer breakfast. “As funding becomes available, with this

plan, at least we’ll know how to use it.” As Langfelder would do more

than a decade later, Davlin’s administration in 2008 promised a

year-round day center for the homeless, and by the end of the year, at a

location to be determined. It didn’t happen.

Funding

is available now, judging by what other communities have received in

HUD grants for the homeless. And federal money appears to have made a

difference elsewhere.

Davlin’s

10-year plan set a goal of increasing the number of affordable housing

units by 200, with the mayor’s task force in charge of keeping track.

The task force disappeared years ago.

According

to HUD databases, the continuum of care that includes Springfield last

year counted 173 permanent housing beds, which is to say, housing

considered stable and outside emergency shelter walls. It was in

increase of 26 beds since 2015. Macon County, including Decatur, had 171

permanent housing beds last year, an increase of 56 during the same

time period despite having less than half the population as the

Springfield continuum. The continuum that includes Rockford received

more than $1.7 million in HUD homeless grants – more than four times the amount as Springfield – and had 1,000 beds.

Rockford has been held up as a national model in the New York Times and Wall Street Journal for getting homeless people from the street into housing – according to the Journal, Rockford housed 200 veterans between 2015 and 2018, and just three veterans were homeless in Rockford when the Journal published

its story in December, 2018. Between federal, state and local sources,

the Rockford continuum that covered three counties spent $3.5 million

that year, the Journal reported. According to the United States

Interagency Council on Homelessness, Rockford is one of four communities

in the United States that has eliminated chronic homelessness, as

measured by federal criteria and benchmarks.

Why has it taken so long to make progress in Springfield?

“Sometimes, I think it’s difficult for everyone to play together in the sandbox,” Kelker offers. “We want to change that.”

Not

everyone agrees a study is needed. “I would say no,” says Jonna Cooley,

executive director of Phoenix Center who sits on the continuum of care

board. “We know what the problems are, we know what needs to be done to

address them.”

“I don’t see a lot of cohesiveness”

“A study?” Julie Becker asks, but not in a tone that suggests disbelief.

Four years after starting a do-it-yourself mission to distribute food, clothing, blankets and other basics to the

homeless, Becker has learned that actions are more important than

documents or words. A study, she says, isn’t necessary: “The number of

homeless we have is manageable.”

A

year ago, Becker quit her job as a Henson Robinson accountant so she

could spend more time handing out essentials, buying meals, putting up

folks in motels and sometimes just listening. Last Sunday afternoon, the

St. John’s Breadline parking lot was her base of operations.

A

man more than six feet tall stands very close, telling me about his

latest run-in with police. Last night, he was buying high-octane beer at

a gas station when he was arrested for trespassing – he was accused of

panhandling outside, which was ridiculous. They had him confused with

someone else. “Why would I be panhandling – I had $180 in my pocket?” he

asks. His phone, he says, is worth $300. It’s in a clear plastic bag

along with a business card I’d given him the day before. A few minutes

after we first met, he told me he has schizophrenia.

More

than a dozen people crowd around Becker’s van to receive blankets and

plastic bags filled with t-shirts, socks, deodorant and Irish Spring

soap. “Can I get two bags?” a woman asks. “For you and who else?” asks

Becker. She wants everyone to get a bag before she hands out seconds.

“My husband – he’s over there,” the woman answers, gesturing toward a

concrete ledge about 50 feet away where folks are sitting. She gets

another bag. The man with $180 in his pocket asks for a coat. You’re

already wearing three, Becker points out. “This isn’t fair!” the man

declares. Becker relents with a hoodie. “So what if I got a coat on,”

the man says as he walks away. “I like to change. So what if I got one

on? I don’t have to wear it every day.” Deodorant is especially popular.

“Strong enough for a woman but a man can use it, too!” a happy customer

hoots when Becker hands over his package. “Thank you, Miss Julie.”

The

crowd barely blinks when a man accompanied by a cop walks slowly across

the parking lot. His face is bleeding and swollen – he looks like Rocky

after his loss to Mr. T. An ambulance arrives and takes him away. An

officer questions a man on a bicycle, ultimately letting him go. “Get in

line!” someone demands as Becker keeps handing out bags. It’s not clear

whether the injured man is homeless, but it’s clear the homeless see

this sort of thing all the time.

After

four years of doing this, word has gotten around. Becker says donations

now cover supply costs, but there’s still insurance and gas. Without a

board of directors or a boss, Becker is free to speak her mind, and she

does once the crowd melts away.

Look

around, she says. It’s the weekend. Most every refuge for homeless

people, is closed, but the destitute remain. Too many social service

agencies keep banker hours, she says, and she doesn’t have much use for

the continuum of care. “I don’t see a lot of cohesiveness going on,” she

says.

The

city’s winter warming center, where people sleep dormitory-style on

floor mats, will close this month, so Becker is stocked up on sleeping

bags and blankets in preparation for the migration outdoors. The warming

center on Madison Street is the only place in the city that takes all

comers, so drunks and dopers and those who can’t get along with others

will soon be finding their own shelter, which promises a certain measure

of freedom. No longer will they have to surrender phones, food and

other possessions at the door or be searched with a metal detector. If

they have a significant other, they will be able to stay together

instead being separated and sent to different sleeping areas, one for

men, the other for women.

Springfield

community relations director Juan Huerta long has painted a positive

picture of the city-funded warming center, which is now run by the

Salvation Army. When Reginald Weatherspoon, who’s been homeless and

attends city council meetings, complained last December about

disrespectful treatment, Huerta talked about bingo and movies in the

building where as many as 70 people a night sleep on floor mats.

“Everything is going great,” Huerta told aldermen.

Such

assurances blew up last month, after Joe O’Neill, a homeless advocate,

presented himself as a homeless person at the center. He’d intended to

stay the night but says he left after 45 minutes, having seen enough.

Without provocation, he says, the homeless were cursed at by Tyrone

Hines, who works under Huerta in the community relations department.

“Sit your fucking ass down on a chair and fucking shut up,” O’Neill

recalls Hines telling someone who hadn’t said or done anything to

deserve it. During a 2018 continuum of care board meeting, when Helping

Hands ran the warming center, Huerta also was upbeat. “Juan reported

there had been no major issues so far,” meeting minutes state. “Juan and

Tyrone are there to make sure all is well.”

Two

years later, O’Neill demanded action, writing letters to Langfelder and

the Salvation Army and describing how he had seen Hines deal with the

homeless. Hines, who was paid by the Salvation Army for working at the

center, remained on the job. After follow-up emails to the mayor and

Salvation Army, O’Neill went public and contacted aldermen. Hines then

was relieved of warming center duties. A request for comment from Hines

sent via a city spokesperson went unanswered.

Smith

says safety concerns were part of the reason Helping Hands refused to

run the warming center this year. “You have people who are in crisis,

who are in fight or flight,” Smith says. “They’re homeless. They’re

cold. They’re hungry. They need help, and you pack them on mats on the

floor inches away from each other. That’s not an ideal situation for

healing for anybody.” Police statistics reflect volatility. The warming

center is open five months each year. Since Jan. 1, 2019, Springfield

police have visited 228 times. Disturbance. Remove subject. Fights.

Overdose.

Premise check.

O’Neill

says he’s given up hope that the city or anyone else will provide

decent shelter for the homeless anytime soon. No matter what, he says,

they are human beings.

“They deserve the same thing that I get,” he says. “They deserve respect.”

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].