Illinois sends students with special needs out of state, at high cost to troubled teens.

Ted likes to say he was in the wrong place at the wrong time. He was 17, doing well at a college prep boarding school in Indiana, when a classmate went on a violent rampage while high on a combination of potent drugs. When cops searched that classmate’s phone, they found that Ted had fulfilled his request for LSD, so he got charged with a felony (which is why he asked us not to use his last name).

His defense attorney got a plea deal: Ted could do three months in jail, or six months at a boarding school in Utah. Ted chose Discovery Academy in Provo, expecting it to be like his prep school only with horses and a weekly therapy session.

“When I was packing for there, I was bringing all sorts of things like my lacrosse stick and all my clothes, my cellphone, my wallet…. And as soon as I got there, they take everything away,” he says. “They stripped me completely naked and did a search. Not a cavity search, but I did do jumping jacks.”

Initially considered a flight risk, Ted was put on “run watch,” and had to sleep in the common area on a bare floor. One morning, he woke up in a pool of blood.

“There was a kid next to me, and he sliced his neck with this razor in the middle of the night, like hundreds of times,” Ted says. “When they turned the lights on, I’m like: Oh, I’m in some shit. This is not a normal place.”

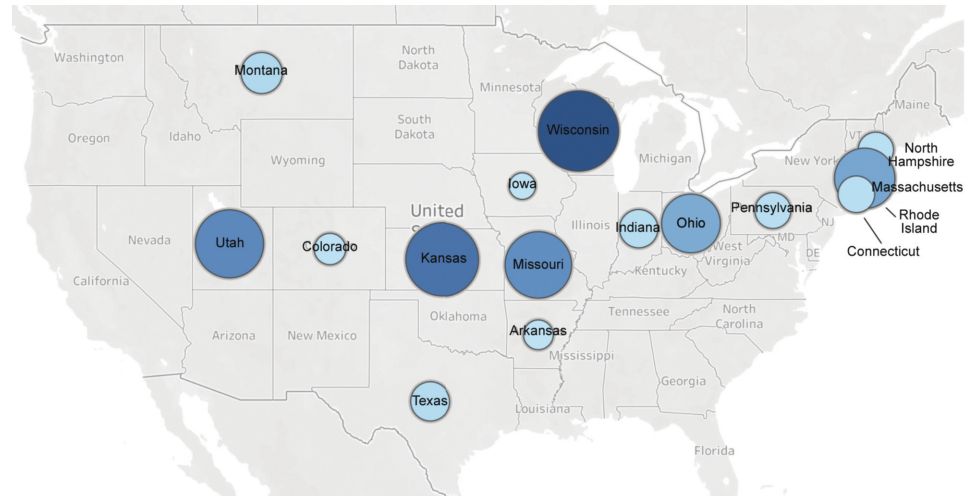

It is, however, a place that Illinois school districts send some students with special needs to live. In the 2017-18 school year, a handful of students (mostly from wealthy suburban Chicago districts) were sent to Discovery Academy or one of its associated facilities, and at least 70 more to other Utah boarding schools. That’s according to documents obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, from the Illinois State Board of Education.

“When they turned the lights on, I’m like: Oh, I’m in some shit. This is not a normal place.”

–Keagan Autry

Utah offers a veritable smorgasbord of boarding facilities for “troubled teens.” A 2016 story in the Deseret News reported that the state had more than 100 such programs, and served more than 6,000 clients in the previous year, more than 92 percent from other states. The report cited a 2015 economic impact study based on survey results from about half of those programs showing they earned about $270 million, contributed $22 million in state and local taxes, and added $423 million to the state’s GDP. In return, the state keeps regulations to a minimum.

Brent Hall, president of Discovery Academy, told Deseret News the industry’s business model was “recession-proof.”

But Ted, now 22, didn’t appreciate being part of Hall’s business. When he was finally allowed to call his parents, a month into his stay, Ted begged his mother to get him out of Discovery Academy and let him do the jail time instead.

“I said that multiple times. Very many times,” he says. “I still say it today.”

Ted’s parents paid for his stay at Discovery Academy. But in the 2018 school year, Illinois paid for at least 344 special needs students to live in private schools in other states. Most were in facilities certified to provide treatment for a range of issues like autism, traumatic brain injury, intellectual and emotional disabilities.

Every child in America has the right to a “free and appropriate public education,” thanks to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, signed into law by President George H.W.

Bush. And if that education

can’t be provided in the student’s home district, the student can go

elsewhere – also for free. Illinois taxpayers typically spend at least

$25 million per year to place hundreds of students outside the state.

Here’s

how that works: If a local school district doesn’t offer the services a

student with a disability needs, the district is required to help fund

that student’s tuition at another facility. The amount the district

contributes depends on two factors: 1) the normal cost of educating a

student in the home district and 2) whether the student is placed at a

public facility (such as a special education co-op) or a private

facility.

That first

factor is known as the district’s “per cap,” and it’s a complicated

calculation dividing the difference between certain district expenses

and revenues by average daily attendance. Across Illinois’ 852

districts, that dollar amount ranges from a low of $5,000 to more than

$29,000. If a student is placed at a private facility, the district is

obligated to contribute an amount equal to two times per cap, and the

state board of education reimburses most of the remainder of the

tuition. If a student is placed at a public facility, the district is

obligated to contribute four times per cap. Federal funds pay for room

and board.

Because the

cost to the home school district is so much higher for public instead

of private placement, many special education advocates argue that

Illinois’ funding structure leaves public facilities starved for

resources while incentivizing placement in private facilities. Melissa

Taylor, past-president of the Illinois Alliance of Administrators of

Special Education (IAASE), surveyed other states and concluded that

Illinois is unique in this funding structure.

“Illinois

is the only state in the nation that funds private special education

placements and public special education placements differently,” she

says.

For more than a

decade, IAASE has been pushing lawmakers to equalize the reimbursement

formula, but private school advocates have lobbied against it. Even with

sponsorship by Democrats in a Democratcontrolled legislature, the

proposal has never even gotten out of committee.

It’s

hard to see how that will change anytime soon, since some of those

public cooperative programs were revealed to rely on seclusion rooms in

the recent investigation published by the Chicago Tribune and

ProPublica. However, that investigation was made possible because the

public facilities are required to document seclusion. New rules enacted

by ISBE in the wake of that investigation will now require private

facilities to document seclusion.

Decisions

about where to place a student with special needs typically begin in

their home district when the student’s parents meet with the special

education team to craft the student’s Individualized Education Plan,

known as an IEP. It’s in these meetings, which happen every three years

(or more often if needed), that the idea of placing a student in a

residential program would be discussed.

Stephanie

Jones, an education attorney and former general counsel for ISBE, says

residential placement is sometimes proposed by the teachers, social

worker, school psychologist and others on the IEP team.

“There

are kids that have very significant mental health disabilities or even

kids that are on the autism spectrum as they get older that can’t be

controlled in a school setting that need a much more therapeutic setting

with people that are trained to handle a lot of violent outbursts,” she

says. “So I’m aware of kids that have, you know, broken plate glass

windows and things like that. And that’s where I’ve seen school

districts actually recommend a residential placement that has

round-the-clock mental health.”

Other times, she says, that request comes from the family.

“I

see the cases where parents just can’t handle the kids at home

anymore,” Jones says. “The kids are either physically aggressive or

behaviorally just cannot be managed in the home environment. And those

are a lot of the types of cases where I see parents coming to school

districts asking for residential placements.”

Jennifer

Smith, a partner in Franczek P.C. (a law firm that represents more than

100 Illinois school districts), says sometimes, a residential placement

happens even before the student has an IEP.

“Under

federal law, parents have the right to send their child to a private

school that they pay for upfront and then seek reimbursement from the

school district, if they believe the school has not offered their child

an education that satisfies a number of complicated legal requirements,”

she says. “Then, after they’ve made the placement, they ask the

district to evaluate the student for an IEP and fund that placement

that’s already been made.”

This

process, known as unilateral placement, is typically used by families

who have substantial financial resources – families who bring attorneys

with them to the IEP meetings.

If the district refuses to create or amend the IEP, the family can

take their case before an ISBE hearing officer. If the officer rules in

the family’s favor, the district is on the hook for not only a chunk of

the student’s tuition, but also legal fees – its own as well as the

family’s.

Tom Tebbe,

executive director of the Illinois Association of School Social Workers,

says more families would take advantage of unilateral placement if they

could.

“Wealth,” he

says, “is a great unequalizer.” Because of that substantial monetary

risk, some districts choose to settle the dispute by offering to just

pay the family the amount the district would owe if it had placed the

child.

Such settlements are never reported to ISBE and aren’t reflected in funding figures we obtained for this story.

Residential

placements come with another type of risk – risk to the safety and

well-being of the child. At least one central Illinois student was

withdrawn from a residential facility, Great Circle in St. Louis, after

suffering physical abuse. In May, Great Circle’s CEO was arrested and

charged with assault and endangering the life of a child. Illinois had

52 students at Great Circle in the 2017-18 school year, according to

data obtained from ISBE.

Also

that year, 55 Illinois students were placed in various private schools

in Oconomowoc, Wisconsin. A suburban Chicago mom, who asked that her

name be withheld, says she was shocked when she visited her autistic son

in one of those.

“I

saw a member of the staff kicking a child who was on the floor, crying

for their mother,” she says. “They had wet their pants, and the guy who

was in charge of the building kept saying, like, ‘Hey! Hey! You want to

see your mom? You’re gonna cut it out right now!’ ” She alerted

administrators, but, dissatisfied with their response, she ultimately

withdrew her son from the school.

“If

[that staff member] did that on the street, he would be arrested,” she

says. “If he’s doing it to one, he’s doing it to others.”

In

January 2019, NPR aired a story about the use of electrical shock to

control autistic students at Judge Rotenberg Educational Center in

Massachusetts, where a handful of Illinoisans reside. A Utah school that

has housed Illinois students closed last year after a riot and

allegations of sexual abuse. Two dozen staffers at that

facility were investigated for child abuse; one staff member was accused

of fathering a child with a 14-year-old former resident of the

facility. The company that owns that school operates several others in

Utah, including one where several Illinois students were placed during

the 2017-18 school year.

In

2018, a therapist who worked at numerous programs in Utah, including at

least two where Illinois students have lived, pleaded guilty to three

counts of first-degree felony rape involving a minor patient.

“I saw a member of the staff kicking a child who was on the floor, crying for their mother”

Smith,

an attorney who attends IEP meetings where some of the decisions on

placements get made, says sending a child out of state should be a last

resort.

“These schools

vary in quality and appropriateness and should not be used unless

they’re truly, truly needed,” she says. “It’s just a balance between

safety and, you know, some of these techniques to keep [students] safe

obviously mean really restricting their freedoms.”

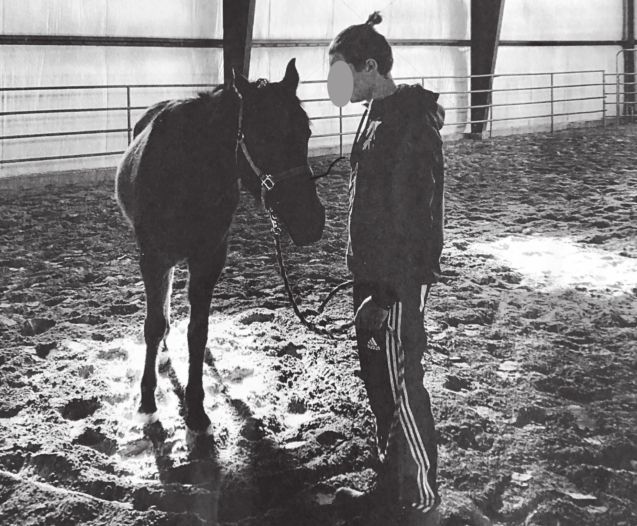

When

it comes to facilities focused on “emotional disabilities,” the

treatment might not be what the parents imagine. Ted – the prep school

student who got sent to Discovery Academy to work off a drug charge –

was disappointed to discover that “equine therapy” didn’t involve riding

a horse.

“They made us try to direct

horses without touching them, like try to direct them around courses

using ‘good communication.’ I don’t know how you necessarily learned

communication from talking to a horse,” he says.

Erin Woolridge, now 42, worked at three different behavior modification programs in Utah – a wilderness boot

camp, Heritage School and Discovery Academy, a few years prior to Ted’s

stay. She confirms his horse tale.

“They

give [students] a horse before they train them at all, and just said,

‘Here, try to bring the horse over here,’” she says. “So the kid … would

be chasing the horse all around, like frustrated because the horse

wouldn’t do what he wanted them to do.”

Once

it became clear the student couldn’t control the horse, the therapist

would compare the student’s frustration to how their parents must feel,

trying to manage their behavior. Woolridge says this strategy was partly

meant to promote empathy with the parents.

“But also,” she says, “it’s certainly a form of shaming.”

Many

schools that offer “behavior modification” still use some version of a

confrontational or “attack” group therapy model that dates back to

Synanon – a drug rehab that morphed into a dangerous cult. Students are

asked to vote on punishment for their peers, and can lose basic

privileges if they resist the program. Ted says he resorted to lying.

“I

mean, I had this whole pamphlet of me promising my therapy, my parents

and myself that I would never drink alcohol. And I wasn’t even old

enough to drink alcohol,” he says. “But I had to sign this packet and

talk about it with my parents in order to graduate the system.”

Avital

van Leeuwen, who’s now 24, found herself at Alpine Academy, another

Utah boarding school, in 2011. She was placed there by the Los Angeles

Unified School District; Illinois placed eight students at Alpine in the

2017-18 school year, according to ISBE.

Like

Ted, she realized there was no escape, and resigned herself to

cooperating, outwardly at least, while inwardly trying to resist.

“Actually,

one of the most traumatizing parts of being there: I had to stand up in

front of everyone and read this speech that they make all of us do

called, ‘Yes, I’m getting better,’ ” she says. “I had to, like, put on

this show and the smile like loving the place and having had a great

experience, when all I was thinking about was how horrible it was and

how much I couldn’t wait to get out.”

She

says the school put her on medication that came with debilitating

withdrawal symptoms when she tapered off, but helped her tolerate Alpine

by making her numb.

“It’s

a spiritual kind of oppression,” she says. “You’re being abused,

emotionally and psychologically, every day by people who are telling you

that they’re helping you, that they love you, they care about you, and

that this is the best for you.”

Keagan

Autry, who’s from Arizona, was one of van Leeuwen’s classmates. To him,

the worst part was the use of social isolation as punishment.

“If you did something wrong,” he says, “you wouldn’t be allowed to talk to people.”

If

you did something “bad enough,” this punishment could last for more

than a week. And the worst thing you could do was kiss a girl.

“There

were cameras in the home, you had no privacy. I didn’t even feel safe

in my own thoughts,” Autry says. “It felt like I wasn’t even allowed to

think badly of Alpine. And I think that’s partially why I started loving

Alpine, in a way.”

For

a couple of years after graduation, he felt intensely loyal to the

school. But troubling memories kept bubbling up in his mind.

“It took a lot of time for it to sink in, just the depths of how wrong a lot of the things that happened there were,” he says.

Looking

back, Keagan Autry – and that’s now legally his name – realizes he was

struggling with gender dysphoria. Alpine is an all-girls school, and

since Autry was assigned female at birth, he was expected to behave like

a girl.

In an email,

Alpine director Christian Egan said school policies have evolved since

then, shifting to honor masculine and non-binary gender pronouns around

2015-16.

“Alpine Academy accepts and affirms our students in their preferred

gender identity and presentation,” Egan wrote. “Students are not

punished for nor discouraged from discussing, exploring, and

experimenting with gender identities different from their birth-assigned

identity or the one initially presented at Alpine Academy.”

In

2018, ISBE amended the school code to try to prevent districts from

sending students to any state that doesn’t provide oversight of

residential facilities. The only state excluded by that provision was

Utah.

Stephanie Jones

was general counsel for the State Board of Education in 2017, and she

advocated for the change. But today, she acknowledges that families

quickly resorted to unilateral placement as a workaround.

Why would parents want to send kids someplace all the way on the other side of the country, and there’s no oversight?

“That is a fantastic question,” she says.

“I

have never understood why – when we’ve raised issues that the

[out-of-state] school doesn’t have special education teachers or doesn’t

have oversight by DCFS – why either parents or hearing officers or

parents’ attorneys think that they’re appropriate placements.”

Utah

recently instituted new oversight provisions, but Smith, an attorney

who represents dozens of school districts, says she has no way to gauge

the new law’s effectiveness.

“These

places are so far away, there’s no reasonable way to monitor from

Illinois, whether they’re safe or unsafe,” she says, “let alone

effective for students with disabilities.”

Dusty

Rhodes is Education Desk reporter at NPRIllinois. This story is an

excerpt of her fivepart series that aired last month. To read the series

and listen to the stories, go to NPRIllinois.org and type Far From Home

into the search box.