As white flight continues, city schools make diversity cool

New Berlin, a village with 1,500 people separated from the outskirts of Springfield by 12 miles of pale blue skies and sunlit cornstalks, still has many hallmarks of a small town. It hosts the county fair, with chili cookoffs, livestock exhibitions and country music stars drawing crowds during the long days of June. Tractors occasionally join traffic on the main thoroughfare, and freight trains rumble and screech along tracks that travel the length of town. And, of course, the people in New Berlin, like much of rural Illinois, are almost entirely white.

Unlike a lot of rural towns, though, New Berlin is growing, and its schools in particular, with nearly 5 percent annual growth, are booming. Its elementary school attendance has more than doubled since 2003. The growth in the higher grades has been slower, but still some of the highest in the metro area.

The schools shape the town’s identity.

German immigrants founded New Berlin in 1865, so, appropriately, the schools’ mascot is the pretzel. And Pretzel Pride is everywhere, from the stands at the baseball diamond, where the high school squad played en route to its first regional championship this year, to the top of the village water tower, which proudly proclaims the town to be “Home of the Pretzels.”

Students are surging into New Berlin schools, though, not because of the town’s rural charm, but because of its proximity to the suburban sprawl of southwest Springfield. As developers turn farmland into new homes, they are increasingly leaving the boundaries of Springfield’s core school district – District 186 – to do so. Even homes that are within the city limits of Springfield often don’t fall within the school district, because those boundaries aren’t the same. The decade-old, half-million-dollar houses in Springfield’s Centennial Park Place neighborhood, for example, barely fall inside the New Berlin school district.

The same thing is happening on nearly every side of Springfield; city residents, in fact, now go to seven school districts other than District 186. In the Chatham school district, more than a third of students have Springfield addresses.

The families landing in Springfield’s suburban districts are overwhelmingly white, and that has profound implications for District 186. The district has been under a desegregation order since 1974 and is legally obligated to provide black students with similar opportunities as white students. At the same time, though, the district is losing white students to neighboring districts.

The white flight undermines the goals that the desegregation order was meant to address, by re-creating

separate but unequal education systems for black students and white

students. Because schools are so closely tied to the neighborhoods where

they are located, the rush of white families to suburban schools also

leads to widening differences for the health, economic opportunities and

quality of life between black and white residents in the Springfield

region, as well.

The

change is happening quickly. The number of white students in District

186 declined by a third in the 15 years between 2003 and 2018, but the

number of black students in the district grew by 3 percent. Meanwhile,

in the rest of the Springfield metro area, the number of white students

only decreased by 4 percent. The number of black students in those

outlying districts more than doubled, mainly because there were so few

in those districts to begin with.

The consent decree: Correcting one problem, ignoring the big picture

Springfield’s

District 186 is one of a few school districts still working under a

federal desegregation consent decree. A group of both black and white

parents sued the district in 1974 for concentrating black students in a

handful of schools. They pointed out, for example, that 78 percent of

all black students in the district at the time attended Southeast High School.

The

school district and the plaintiffs agreed to a consent decree within

months. The court found that the district violated the Fourteenth

Amendment by “contributing to the creation, intensification and

perpetuation of racial segregation in and among the public schools of

Springfield School District 186.” The district, the federal judge added,

had an “affirmative obligation to eliminate and prevent racial

segregation in the public schools of District No. 186.”

The

agreement prevents District 186 from using many of the tactics that led

to the segregation in the first place. That includes drawing attendance

zone boundaries that result in racially segregated schools, creating

school-to-school transfer policies that resulted in racially segregated

schools, assigning faculty or staff based on their race or ethnicity,

sending less-qualified staff to predominantly minority schools,

unequally distributing supplies and equipment among schools, applying

tracking systems that discriminate between pupils based on their race,

setting up systems that disproportionately subject minority students to

discipline or offering extracurricular activities in a way that

discriminates against students on the basis of race.

As

far-reaching as the consent decree was, its biggest weakness is the

fact that it only applies to a single district. During the months while

the Springfield desegregation case was pending, the U.S. Supreme Court

handed down a landmark decision in July in a Detroit-based desegregation

case called Milliken v. Bradley. It was a 5-4 decision, and four of the

five judges in the majority had been recently named by then-President

Richard Nixon. The majority ruled that, in all but the most egregious

circumstances, courts could not impose school desegregation plans that

involved transferring students from one district to another. In other

words, Detroit’s predominantly white

suburban school districts would not be forced to integrate with

Detroit’s increasingly black schools. And, of course, neither would

Springfield’s.

The

Detroit case marked a turning point in how the Supreme Court handled

school desegregation cases. Twenty years after Brown v. Board of

Education, the justices began limiting the circumstances and scopes

under which minority residents could force racial integration of

segregated schools. That culminated in a 2007 case in which the court

ruled that schools could not consider the race of students when

assigning them to schools. “The way to stop discrimination on the basis

of race,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote, “is to stop discriminating

on the basis of race.”

Still,

District 186 has never challenged its consent decree. A federal judge

continues to monitor the process, and the district generates 1,000-page

reports every year for local civil rights leaders to review.

Huge

demographic shifts, though, have made many of the order’s objectives

harder to meet. White residents have moved farther away from the city

core, especially to Springfield’s sprawling west side or to nearby

towns, like New Berlin, that have become bedroom communities. The

population of black residents has grown, and those residents have spread

from the traditionally black east side of town to other parts of

Springfield, but rarely the suburbs.

That

means racial segregation in the Springfield metro area is no longer a

problem only within the city, but also across the entire metropolitan

region. The schools reflect that shift. Calculations from Governing magazine

earlier this year showed that, for schools in District 186 to all

reflect the same black-white distribution of the district as a whole,

about 18 percent of students would have to go to different schools. But

across the whole metro area – city and suburbs alike – 63 percent of

students would have to be reassigned to match the region’s racial

makeup.

These days,

black students (40 percent) in District 186 make up almost as big of a

share as white students (44 percent). Nearly 11 percent of the

district’s students identify as more than one race, 3 percent as

Hispanic and 2 percent as Asian.

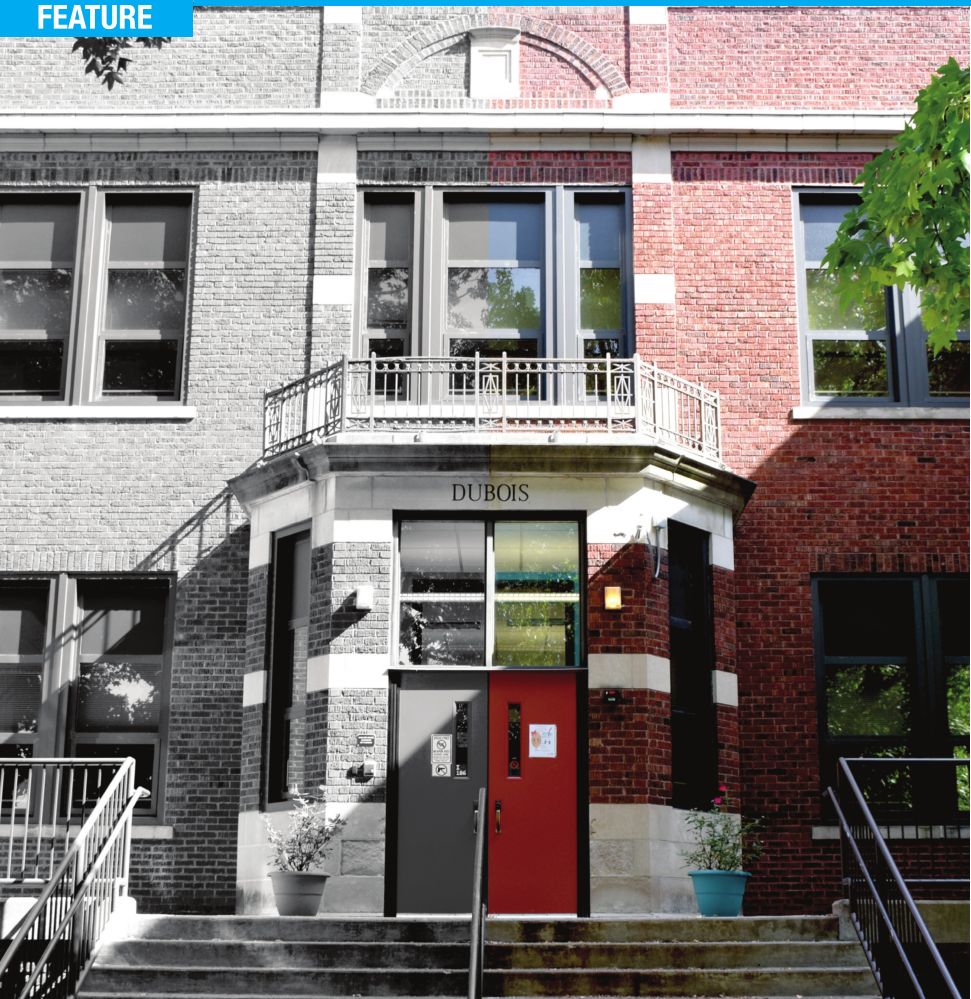

DuBois deals with demography

DuBois

Elementary School, a century-old brick building in Springfield’s

historic west side, has seen the same dramatic demographic shifts as the

district as a whole. In 2003, white students made up 62 percent of

DuBois’s 494 students. Now, they make up 32 percent of the students,

even though the school is smaller. Black students, which make up 51

percent of the student body, are now the biggest demographic group. Kids

who identify as two or more races make up another 13 percent.

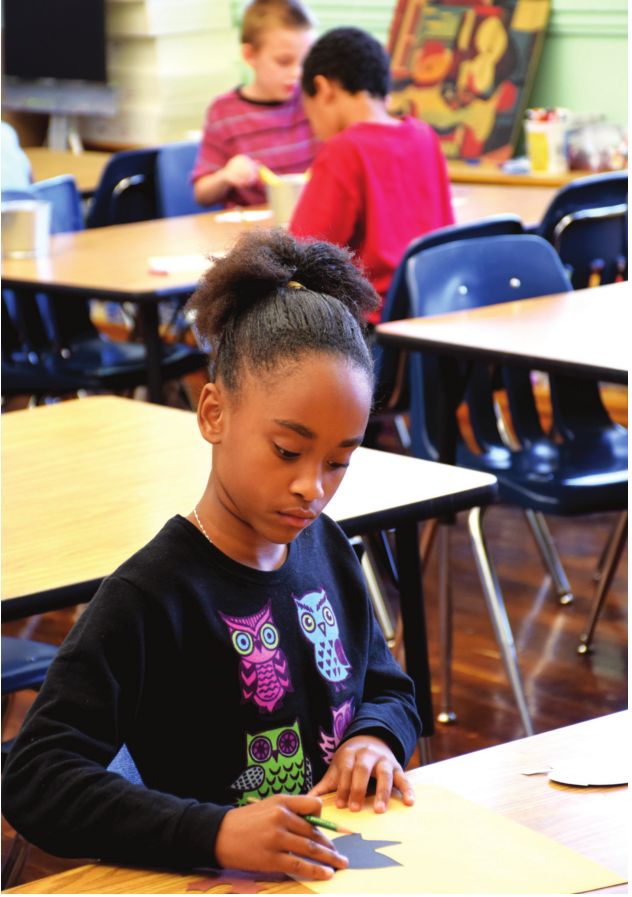

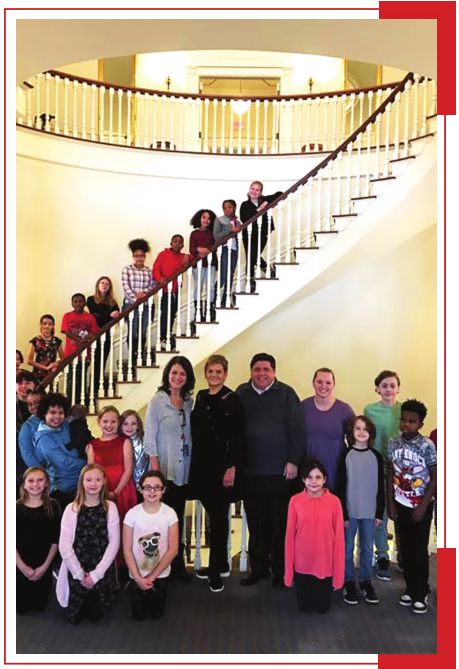

Teachers

and administrators there go out of their way to cater to the different

learning styles and needs of the diverse student body. The school

emphasizes hands-on learning for its STEAM-based curriculum that helps

students explore science, technology, engineering, art and math

simultaneously. Earlier this year, a group of fourth- and fifthgraders

explored real-life examples of art with a tour at the newly renovated

executive mansion downtown, which ended with a meeting with Gov. JB

Pritzker. One of DuBois’ teachers, Dan Hartman, is one of 10 finalists

for Illinois’ teacher of the year this year.

“We

believe that every child learns in a different way and every child

needs a varied approach to learning,” says Donna Jefferson, the school’s

energetic principal. “We emphasize hands-on, experiential, real-world

learning.”

Jefferson

also wants the DuBois community to help students and teachers grapple

with problems outside of the classroom, too. Amber Alexander saw that

firsthand. She enrolled her two kids in DuBois, in part so they could be

closer to her ex-husband. But when her ex-husband died last May,

teachers from DuBois attended the funeral. People from the school called

her to make sure the children were doing all right. Her daughter’s

teacher had the class make condolence cards. “It was a really supportive

environment,” Alexander says. “I like the fact that they’re like a

family.”

None of those

intangibles, though, show up on standardized test results or online

school rankings. GreatSchools, a nonprofit organization that calculates

the school rankings that appear on real estate websites like Zillow or

Realtor.com, ranks DuBois a “3” on a 10-point scale.

Outside

perceptions of schools can shape nearby neighborhoods. Home buyers

nationally say that getting into a good school district is their top

priority in purchasing a house, and three-quarters of those who

responded to a survey last year said they had to give up amenities like

garages, updated kitchens or big backyards to get the school they

wanted, according to the National Realtors Association. Nearly 60

percent of respondents said good test scores were a hallmark of good

schools.

“School

districts are an area where many buyers aren’t willing to compromise,”

wrote Danielle Hale, the group’s chief economist, last year. “For many

buyers – and not just buyers with children – ‘location, location,

location,’ means ‘schools, schools, schools.’” District 186 does use

some tactics that other urban districts have tried in order to keep

white families from leaving: it opened selective schools for gifted

students after a charter school opened in 1998. The district’s two

schools for gifted students draw a disproportionately large number of

white students. At Iles Elementary, for example, more than half of the

pupils are white, 18 percent are Asian and 14 percent are black. Half of

the students at both Benjamin Franklin Middle and Lincoln Magnet School

are white. The district’s single charter school, Ball Charter School,

has a racial makeup that more closely resembles that of the district as a

whole.

Aaron

Graves, the president of the Springfield Education Association, the

local teachers’ union, worries about the effect that the selective

programs have on other district schools and their efforts to improve

their academic performance. “These schools are doing fantastic things

with their kids, but if you take 80 gifted kids from Washington and 80

gifted kids from Jefferson [both middle schools with more than 70

percent low income students], how are those schools ever going to right the ship?” he asks.

Superintendent

Jennifer Gill notes, though, that those programs have all been in place

for decades. Almost all school districts serve gifted students with

distinct programming, she adds. They

were created, she says, as “a place to serve gifted students. They were

not put in place to prevent white flight.”

“My

school district hires me to serve the students that are here,” says

Gill. “We’re comparing ourselves to school districts that are outside of

suburbia. Yeah, we look different. We don’t have a large seven-lane

swimming pool at each of our high schools. We’re operating inside our

means. I don’t try to compete with my local neighbors. I try to just

make sure that I serve our students.”

For years, the Ball-Chatham

School District has offered Springfield-area residents a suburban

alternative to District 186. But Ball-Chatham Superintendent Douglas

Wood says that doesn’t put the two districts in

conflict. “I wouldn’t necessarily say it’s a competition. I think many

of the school districts around us do a wonderful job,” he says.

But the different districts cater to different family priorities, Wood says. Some families from smaller communities

might be looking for smaller school districts. When Chatham

administrators do look around at other school districts for comparison,

they look to suburban schools in the Champaign, Peoria and Chicago

areas, not just the Springfield area, Wood says.

The

Williamsville-Sherman school district north of Springfield has seen

some of the fastest growth of its schools in the metro area over the

last 15 years, particularly in its elementary and junior high schools.

Again, the vast majority of the growth has come from an increase in

white students.

Superintendent

Tip Reedy says new residents come there because of the schools, not

racial homogeneity. The schools, he says, rank high in state ratings and

are small enough that kids don’t get lost in the system. “That’s all I

ever hear from the community: Great schools equal great communities,” he

says.

New Berlin school board president Bill Alexander

suggested that the move of predominantly white families to the district

was “more economic flight [than] white flight,” because minority student

enrollments had increased in many suburban districts, even though the

overall numbers remained small. A quarter of students in the New Berlin

school district are from low-income families.

While

economic factors certainly play a role in white flight, there is also a

growing body of research that suggests that race – not economics – is

the root cause of the phenomenon.

The

Pew Research Center found this year that 62 percent of white Americans

said it was better for students to go to school in their own

communities, even if the schools weren’t racially or ethnically mixed.

By comparison, 35 percent of white Americans favored diverse schools

over local ones. Black Americans responded almost exactly the opposite

way: 68 percent favored the diverse schools, while only 28 percent chose

local schools.

And if

economic conditions did explain white flight, whites would migrate to

the same places that middle class black, Asian or Hispanic residents

moved to, says Indiana University sociologist Samuel Kye. “Almost all of

our metro areas have diversified, but those trends have not trickled

down to neighborhoods,” he says. In fact, Kye’s research found that

whites in middle class suburbs are more likely to move when minorities

arrive than whites in poorer areas.

The demographic shifts in District 186 have not made it easier to address longstanding race-related concerns.

Take

the school board. Only two of its seven members are black, and that’s

only been true since September, when Tiffany Mathis was appointed to

fill a vacancy. There have occasionally been two black members of the

board before (although never more than two), but for most of the last 19

years, Judith Ann Johnson has been the board’s only black member.

Johnson

says she gets more constituent calls than most board members, because

black families call her for help, even if they don’t live in her

subdistrict. She knows she has a reputation for being outspoken and for

asking tough questions. “People don’t like me, because I’m vocal,” she

says. “When it comes to educating kids, I feel my kids should get the

same thing as everybody else’s kids.”

Another

major concern is the recruitment and retention of black teachers. In

1975, only 5.9 percent of Springfield’s teachers were African- American.

By 2016, it was only 9.7 percent. The numbers have remained stubbornly

low, even though the district has a full-time recruiter dedicated to

finding minority candidates.

Gill,

the superintendent, says a statewide teacher shortage is to blame.

Fewer college students overall are going into education to begin with,

and, during Illinois’ recent budget crisis, many of them went to

out-of-state colleges. Until recently, though, Illinois required

teachers to take additional coursework if they were transferring in from

other states.

Other

issues may be at play, too. Some black teachers who have worked in

District 186 say they also have felt unwelcome among their colleagues in

certain schools. The district doesn’t offer moving expenses or any

other incentives to move to Springfield. Union rules that required the

lasthired teachers to be the first to be laid off made it harder to keep

new black teachers in the aftermath of the Great Recession. Plus,

somewhat ironically, the district has focused on promoting qualified

black teachers into administrative roles, but it has had a hard time

replacing them in the classroom.

And even after nearly half a century of living under the desegregation order, there is still a widespread perception that

the racial makeup of many schools is skewed, especially when it comes to

the district’s three main high schools. White students make up the

majority at Springfield High School, where they outnumber black students

2 to 1. At Lanphier High School in the north, whites make up 48 percent

of students, compared with 39 percent for black students. And Southeast

has a bigger share of black students (50 percent) than white students

(40 percent).

But

Gill, the Springfield superintendent, says the desegregation order still

plays an important role in how the district operates. District

officials have never considered challenging it, says Gill, who attended

DuBois as a child and taught in the district before eventually leading

it.

“I’ve never been a

student, an educator or a superintendent who was not under the

desegregation order and the consent decree,” she says. “So why would I

live any differently than by the full letter of the law? It’s how I was raised, and how I was brought through the system.”

While

Springfield schools wrestle with the consent decree’s requirements,

though, the growth of the suburban schools all around them continues. In

New Berlin, in fact, local leaders are exploring options for replacing

the centuryold building that hosts the junior and senior high schools to

handle the burgeoning demand. The district already opened a new

elementary school in 2009.

Daniel C. Vock is a national public policy reporter based in Washington, D.C., and a former staff writer for Governing magazine. He led a Governing team that reported the “Segregated in the Heartland” series earlier this year. Vock lived in Springfield from 1999 to 2005.