Normal welcomes Rivian, and the future

If Mayor Chris Koos looks pleased as he tells the tale, it’s understandable.

It was about five years ago, the mayor of Normal recalls, that that a barely known entrepreneur came to town looking for bargains. The Mitsubishi plant was closing after more than 25 years of building cars in the town about half the size of Springfield and 60 miles north of the capital city. Nearly 1,300 jobs – down from a peak of more than 3,000 in 1995 – would be lost when the Japanese automaker, the sixth-largest employer in the metropolitan area, stopped production.

Mitsubishi said the factory, opened in 1988, wasn’t needed any longer, just another Rust Belt casualty. The 2015 closure announcement had been preceded by years of cutbacks and job reductions, signs of the industrial age’s twilight and the state’s dismal economic prospects.

The factory’s fixtures and equipment would be auctioned – just the thing for someone starting up an assembly line from scratch. And so Robert “R.J.” Scaringe, CEO of a fledgling car company that a few years later would set the automotive industry on fire, sent a team to see what might be worth buying. Executives were impressed beyond what they saw at the plant.

“They told us, ‘We go into these towns and all we see is a rusting factory, a Holiday Inn Express and an Applebee’s,’” Koos remembers.

That isn’t Normal, a town that has bet big on urban renewal and appears to, so far, be winning. And Rivian, Scaringe’s company, isn’t an ordinary bottom feeder.

“There’s a buzz going on in this community, and we like it,” Koos says.

“I’m going to go so fast”

Founded in 2009, Rivian captured imaginations last November when it unveiled prototypes of an electric pickup truck and an electric SUV that the company says will go into production in 2020.

Believers include Ford, which announced last spring that it was investing $500 million in Rivian. Cox Automotive, publisher of Kelley Blue Book and autotrader.com, last month announced a $350 million stake.

The biggest coup has been Amazon, which announced a $700 million investment in February, less than four months after Rivian unveiled prototypes. In September, Jeff Bezos, Amazon CEO, said that his company will buy 100,000 delivery vans from Rivian, with the first ones expected to hit the road in 2021.

No price tag has been set for the vans.

Rivian says its pickup trucks will start at $69,000, with SUVs starting at $72,000. You can reserve yours with a $1,000 deposit – the company accepts credit cards on its website.

Mayor Koos says he’s

already reserved vehicles for the town – he has enough confidence in the

company that he did it on his own, betting on getting reimbursed (he

was right), even though Rivian hasn’t said how far down Normal is on the

waiting list. “I’m sure we’ll get some consideration,” he says.

A

central Rivian engineering concept, dubbed the skateboard chassis, is

simple enough for English majors to grasp. A rectangular, relatively

thin battery pack that the company says is among the largest ever

produced for automotive purposes, is at the bottom, taking up most of

the space between the vehicle’s four wheels and resembling a flat

platform, thus the skateboard moniker. Ballistic underbody shielding

protects the battery from rocks, curbs or whatever else the vehicle

might encounter. Each wheel has its own motor, each motor capable of

producing 200 horsepower. The battery and motors plus air suspension and

braking systems all lie at or near axle level, ensuring a low center of

gravity, optimal handling and storage space where the motor and

drivetrain would be on a conventional vehicle.

It

adds up, the company says, to vehicles that can zoom from zero to 60 in

less than five seconds and travel as far as 450 miles on a single

charge. Retired NBA star Shaquille O’Neal has sung praises, posting a

video of all 7-foot-one, 300-plus pounds of himself slipping comfortably

into the cab of a Rivian R1T, the company’s pickup, even though he

isn’t a paid endorser. “Shaq fits,” tweeted Scaringe, who has been

dubbed Tesla’s worst nightmare by Forbes magazine. Rivian has

struck a deal with Alex Honnold, a rock climber best known for climbing

El Capitan without ropes, harnesses or other safety gear. Honnold, who

once lived in a van, has said that he plans on using a Rivian to drive

through the backcountry to get to climbing sites.

“Alex

and I, when we first met, we really connected,” Scaringe said during a

June discussion with Honnold livestreamed by Rivian. “In many ways,

while we’re doing different things, we have that similar drive to do

something that is very hard and requires a lot of persistence. It’s not

something that you can do in a day or do in a week or do in a year.”

Rivian

and Honnold last summer announced plans to deploy used batteries to

Puerto Rico, where the company and a foundation headed by Honnold that

promotes solar energy will use them to store electricity for municipal

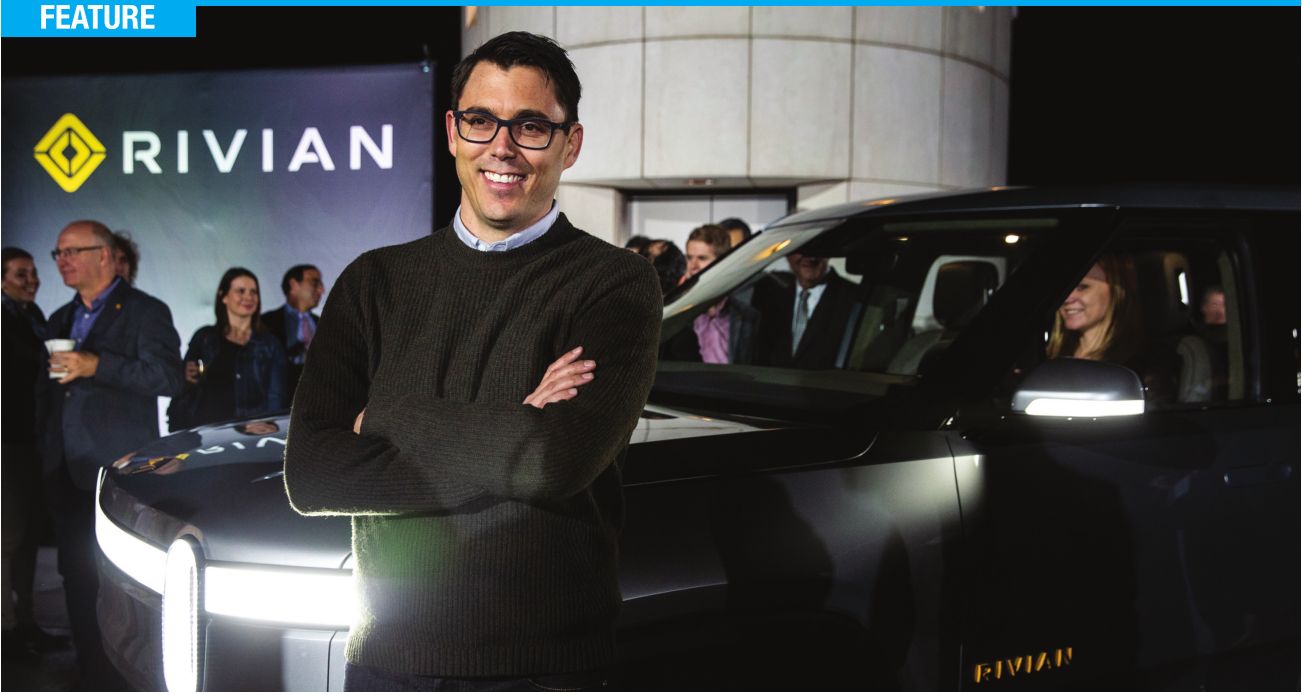

use. Looking a bit like Clark Kent in black-framed glasses and neatly

combed hair – it's a common comparison on websites – Scaringe during

last summer’s discussion with Honnold explained that batteries from

prototypes, test vehicles and other vehicles that are past their useful

lives still have as much as 80 percent of storage capacity remaining,

and so the company is designing them so that they can be reused instead

of scrapped.

There is

another side, which Honnold pointed out during his talk with Scaringe,

who is in his mid 30s and holds a doctorate in mechanical engineering

from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“When

I first learned about the Rivian trucks, I said ‘This is going to be

incredible – I’m going to go so fast,’” Honnold said. “Obviously,

there’s the alignment in values and what we hope to do in the world. But

also, at a certain point, you just want to drive a truck real fast.”

“The community runs the plant”

During

his hour-long discussion with Honnold, Scaringe spent nearly as much

time talking about the Normal factory as he did solar energy or electric vehicles.

The

coffee table in front of him, Scaringe boasted last summer, was made by

employees who haven’t yet started mass producing cars. Rivian, he said,

will be no ordinary car company. “Normally in a plant, it’s

clock-inclock-out,” Scaringe said. “This is a team that’s coming in on

weekends to build kickass tables for us to use at things like this or in

conference rooms at the plant.”

The

plant was a bargain, considering its size and nearly $250 million in

incentives the state offered Mitsubishi to build it 30 years ago. This

time around, the state has granted nearly $50 million in tax credits

over 10 years, conditioned on job creation and capital investment; the

town of Normal has approved a $1 million grant to be paid if Rivian

invests $20 million over five years, and the company also is eligible

for property tax abatement based on investment and job numbers. Rivian

paid $16 million for the 2.6 million-squarefoot factory that sits on

slightly more than 500 acres.

“Most

of it’s just grass,” Scaringe said during last summer’s livestream.

“We’re going to be turning a lot of that into an area to grow food.” The

company will form partnerships with universities, Scaringe said, and

students under the supervision of top chefs will prepare food onsite

from crops grown on the property to feed employees.

“A

big part of what we’re actually doing right now is mapping out and

thinking about the psychology of our company and the psychology of our

facility,” Scaringe said last summer. “We want it to be a benchmark for

how industrial systems are run.”

Illinois Times wasn’t

successful in securing an interview with Scaringe, who made time for a

Bloomington-Normal Economic Development Council dinner last fall, just

one month before Rivian created a sensation by unveiling prototypes in

Los Angeles. Clad in jeans and a sport coat, his recollection of how

Rivian ended up in central Illinois matched Koos’ memory.

A

team in search of equipment and fixtures, not necessarily real estate,

called after visiting the plant, Scaringe told dinner attendees, and

urged him to fly out. “They said ‘This plant is amazing,’” Scaringe

recalled. “I said ‘What else?’ They said ‘The community around it – this

is a genuine place. We just spent an hour in a bar. The people are

really nice.’” And so Scaringe, accompanied by board members, came to

Normal. The board, Scaringe told the audience, spent more time looking

at the area around the plant than the factory itself.

“People

run the plant, the community runs the plant,” Scaringe said. “There’s a

community here that has a passion and an energy to bring something

special, energy to do something cool, to do something impactful, not

only to bring the plant to life, but to grow and build. We were very

fortunate and continue to be impressed.”

During

a half-hour spent talking and answering questions at last fall’s

dinner, Scaringe spent considerable time describing his vision of the

automotive future. Rivian vehicles, he said, will be able to drive

themselves on highways. “You can take your hands off the wheel, your

eyes off the road, you can be on your phone, you can be watching movies,

you can be talking,” Scaringe said. “It means that, on the highway, you

can get some of your time back. For us, it’s an important feature

because it speaks to our brand.”

Some

entrepreneurs can get ahead of themselves, and Scaringe did exactly

that when he told the crowd last fall that automatic braking systems

would be standard equipment starting this year. “By regulation in the

United States…in 2019, every new vehicle sold will have something called

automatic emergency braking, which is a neat feature,” Scaringe said.

“It means that the days of rear-ending the car in front of you will be

over.”

That’s not

true. While automatic braking systems are offered on some vehicles, such

systems are not mandatory. Rivian, also, has missed benchmarks required

to receive tax breaks.

Scaringe

told the economic development council last fall that Rivian employs 60

people in Normal, more than the 35 required to get property-tax

abatement, but it hadn’t invested $10 million, as required by the

abatement deal made with McLean County, Normal and other taxing bodies

and so no break was given last year. The five-year tax abatement plan,

with annual targets, calls for the company to invest at least $40.5

million at the plant and employ at least 500 people by 2022. The company

also didn’t invest enough last year to qualify for state tax credits.

Rivian

must invest $22 million and employ 75 full-time workers by the end of

this year to get 2019 property taxes abated. Patrick Hoban, chief

executive officer of Bloomington-Normal Economic Development Council,

doesn’t sound worried. “We’re pretty sure they’re going to blow that out

of the water,” Hoban said. “It’s definitely the real deal.”

Not everyone is convinced, according to the mayor, who calls Scaringe “brilliant.”

“Believe it or not, there’s been some skepticism in the community,” he says with a twinge of sarcasm. “It’s dwindling.”

Redevelopment and economics

That Rivian would be attracted to Normal, and the neighboring city of Bloomington, isn’t surprising.

Beyond

the plant and a workforce left over from Mitsubishi days, the

Bloomington- Normal area has proven resilient, with populations in both

municipalities increasing during the past two decades while other

downstate towns have lost residents. While other universities struggle

for students, enrollment at Illinois State University in Normal has

increased by nearly 13 percent since 2015. Illinois Wesleyan University,

a private school in Bloomington, has seen enrollment dip from 2,090 in

2011 to 1,636 students this fall.

Between

the two schools, the Bloomington-Normal area has more than 22,500

college students, and Normal’s central business district looks it, with

three record stores, plus a head shop, on a single block along with

plenty of ice cream parlors, coffee shops (Scaringe spent time at one

called the Coffee Hound during his initial visit) and restaurants within

easy walking distance of each other. Parking is free. An Amtrak station

that opened seven years ago is a centerpiece, with Greyhound and local

buses offering service to and from the station. City Hall is housed in

the station’s upper floors. Mark R. Peterson Plaza outside is named for

the former city manager who retired last year after 20 years of running

things.

Dubbed Uptown

Normal, the area has been a focus of redevelopment efforts that began in

1999, four years before Koos became mayor. The town has spent $90

million, by the mayor’s calculations, which has leveraged $172 million

in private investment, including two hotels. The town also is building

new fire stations. Property tax rates have been increased annually since

2006, and the per capita debt load is $1,725, high for a municipality

of Normal’s size, the town’s finance director acknowledged in a story

published last year in the Bloomington Pantagraph.

“Every

big project was a fight,” says Koos, who won re-election two years ago

by 11 votes. “It was hard. But once it got done, people embraced it.”

Did

redevelopment at the town’s core help lure Rivian? “It had a lot to do

with their decision, according to them,” Koos answers.

A

few miles away at the Downtown Bloomington Farmers Market, Brad Dearing

isn’t so sure. “I’d say it’s apples and oranges,” says Dearing, a high

school teacher who also runs

a 30-acre farm near the Rivian plant. The amount spent on redevelopment

has irked some, says Dearing, who sees another side. “By spending that

money, whether you like it or not, it improves the community,” he says.

The

Bloomington-Normal area, Dearing points out, is economically diverse,

with State Farm Insurance and Country Financial the largest employers.

With more than 130,000 residents between the two municipalities, the

area also has an industrial heritage. In addition to Mitsubishi in

Normal, Electrolux, maker of vacuum cleaners, once called Bloomington

home but left in 2012. “You’ve just got a neat mix of people,” says

Dearing, who grew up in Petersburg. “And you’ve got the rural side. It’s

kind of that small-town feeling in a big town setting. I think Rivian

can help with that, with some of the things they’re saying they’re going

to do.”

Bloomington

Mayor Tari Renner, who is a political science professor at Illinois

Wesleyan University, predicts that his city will benefit.

“We’re

going to have economic spillover for the entire community, even the

entire region,” Renner says. “I think it’ll not just be the economic

boost that we will get in the immediate area in terms of jobs and

investment. It will also be a psychological boost by putting us on the

map.”

Renner says

confidence in Rivian, including his own, has increased with time.

“You’re burned all the time, people who say they want to do something

and they’re not able to deliver,” Renner says. But Bloomington- Normal,

he says, has never seen anything quite like Rivian. “There are no red

flags, I would say,” the mayor said. “Everything we see seems to be

positive.”

Dearing,

who teaches technology classes at University High School in Normal, once

took students on tours of the Mitsubishi plant and says he’ll likely

ask Rivian if the company will permit visits. The company allows

household hazardous waste collections in its parking lot, and it’s given

permission for the Children’s Discovery Museum in Normal to hold a

pushcart derby next fall. The annual derby in which teams of students

build carts, then race them, had outgrown a parking lot near the central

business district. “We contacted them and said ‘This sounds like a good

partnership,’” recalls Rachel Carpenter, the museum’s education

manager. “They said yes, and we were thrilled.”

Last

Saturday, Corbin Streenz, 3, got a head start on the derby as he rode a

pushcart powered by his mother, Marie, during a children’s festival in

the redeveloped Normal business district. Marie Streenz said she’s not

much a fan of Normal’s makeover – too many historic buildings have been

sacrificed, she says, and she doubts redevelopment was a factor in

Rivian buying the Mitsubishi plant. “It was a right price, right time

sort of thing,” Streenz says. She is an unabashed Rivian believer.

“I can’t wait,” she said. “I think it’s awesome. It’s good news for this community.”

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].