The future of Republicans in Illinois

With the unpopular term of Gov. Bruce Rauner and divisive politics of President Donald Trump, coupled with a state that’s been losing population and a shifting demographic, Republican leaders are facing an uphill battle to maintain their place in Illinois politics.

The typically Republican stronghold in the collar counties around Chicago – Kane, DuPage, Lake, McHenry and Will counties – was tested in the 2018 midterm elections, where the GOP lost two congressional seats to Democrats, not to mention a party shuffle that occurred in local government in DuPage, Lake and Will counties.

In the 2018 midterm elections, Democrats picked up three senators and seven representatives among DuPage, Northeast Cook, Lake and Will counties, making way for a “blue wave” in the suburban counties outside of Chicago.

Republican incumbents’ recent loss of the 6th and the 14th Congressional Districts to Democrats should be looked at carefully. U.S. Rep. Sean Casten, D- Downers Grove, ran in the 6th Congressional District as a first-time candidate with a campaign platform that focused on climate change, immigration and education, defeating incumbent Peter Roskam.

“I certainly believe that the Illinois Republican Party has lost its way and its effectiveness,” said Jeanne Ives, former representative of Wheaton and a 2018 Republican gubernatorial primary candidate. “It’s obvious because of the election results and the way that our party has been so divided on candidacies at the highest level.”

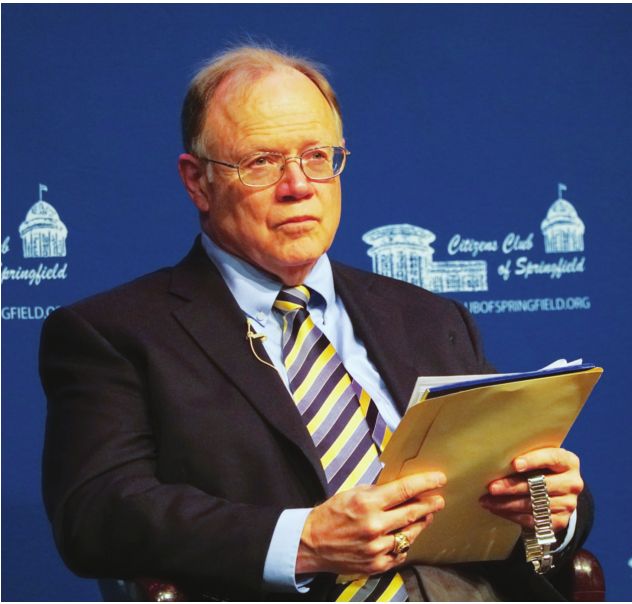

Despite the gloom that’s presently clouding the Republican Party, Mike Lawrence, former director of the Paul Simon Policy Institute at Southern Illinois University and senior policy adviser to former Gov. Jim Edgar, said this isn’t the first time Republicans have looked ahead at rough seas. He said the national attention the Watergate scandal received gave Democrats a supermajority during the following election in 1974.

“When you have a big swing in one direction, it’s difficult to have people write off the opposition party,” Lawrence said. “Those obituaries have proven to

be premature . . . but Republicans, I think, have a steeper climb this

time than some of the political parties have had in the past.”

“I certainly believe that the Illinois Republican Party has lost its way and its effectiveness”

Kent Redfield, political science professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Springfield, said Republicans are facing somewhat of an identity crisis because of their low visibility around the state and a changing voter demographic that’s younger, more racially diverse and more female.

Early estimates indicate the population of Illinois has dropped by more than 90,000 people since 2010, according to data released from the U.S. Bureau of Statistics in December. While that alone isn’t enough to strike fear into the hearts of Republican lawmakers around the state, where those population losses are occurring gives them room to pause.

Redfield said “downstate,” which is used loosely to describe any area outside of Chicago and its surrounding counties, used to be what made elections. He said the collar counties typically vote Republican during statewide elections while Chicago votes Democrat, causing

a canceling out effect. Downstate was previously known for its swing

votes, but that changed around the Blagojevich era when voters began to

support Republican candidates more consistently.

Despite

Republicans gaining votes in the southern part of the state, it has

done little to help the party overall, since most of the state’s

population loss is occurring in that region. The numbers game is

compounded because the areas that tend to vote for Democrats are

increasing in population.

“The

state’s becoming more Democratic nationally, in presidential elections,

and then statewide elections and now the control of the General

Assembly,” Redfield said. “You haven’t had Republicans control either

chamber since 2002. What’s happened there is that downstate has become

more Republican, but it has also lost population.”

Lawrence

and Redfield said the shifting demographics in the collar counties

began in the 1990s and can be attributed to growing populations of

Hispanics and Asians. They also agree the suburban vote is needed if

Republicans want to win elections, but the problem Republican candidates

face is running a campaign that attracts both Republican moderates and

more conservative voters.

“Those

counties around Cook County, with the exception of McHenry, have become

more racially and ethnically diverse and more politically diverse,”

Redfield said.

The

shifting demographics have had a profound impact on the way people vote

in Illinois, Redfield said, which in turn has made it difficult for

Republicans to decide who should run for statewide leadership positions.

On one hand, Redfield explained, the collar counties tend be more

socially liberal but fiscally conservative, versus the southern part of

the state where Trump easily won most counties. Trump received at least

70 percent of the vote in eight counties in southern Illinois.

Redfield

said moderate candidates along the lines of Edgar and Gov. Jim Thompson

would have been more attractive to suburban voters during the 2018

midterms, but the bigger question should be if moderate candidates would

have won the Republican primary. Redfield said there’s hope for

Republicans to pick up areas they’ve been missing out on, with the right

candidate. “Madison County is getable from a Republican standpoint in a

statewide election if you have a moderate candidate.”

Right-wing passion

The

Republican Party has generated a great deal of criticism around the

country since Trump announced his bid for the presidency. Some of the

inflammatory statements he made about minorities then, and since his

inauguration, have prompted accusations that the GOP is now synonymous

with racism.

Ives

received backlash during her 2018 Republican gubernatorial primary for

an ad she ran against Rauner, which most likely didn’t help win over the

voters in areas Redfield and Lawrence say are needed to win races in

Illinois. The ad took aim at some of the legislation Rauner had signed,

including bills to expand abortion coverage and supporting the rights of

transgender people to use restrooms of their choice. Editorials from

newspapers around the state were critical of Ives’ message, with a Feb. 6

editorial from the Chicago Tribune accusing the candidate of “punching down” instead of striking out against her competition.

Despite fallout from the ad, Redfield and Lawrence pointed to leadership on the national level that’s

making it difficult for Illinois Republicans. The most visible

representative of their party is Trump, and he lost most of the

districts needed to win elections in Illinois. The only collar county

Trump won in 2016 was McHenry. “He is unpopular with voters who are

crucial for a Republican comeback in the state,” Lawrence said.

Additionally,

Lawrence said, Republicans aren’t doing a very good job of picking

which candidates should run in particular districts.

Redfield

said he doesn’t doubt that Rauner’s failures were a factor that

influenced Republican losses in the collar counties during the 2018

midterms, but he also thinks it had to do with Rauner being

uncomfortable with issues regarding gender, cannabis legalization and

gay marriage. “Part of the Republicans’ problem is, if they’re going to

run strong in suburban areas, a Jeanne Ives or Donald Trump kind of

perspective on social and cultural issues is a real handicap,” Redfield

said.

However, it

would be a mistake to assume there isn’t a right-wing base in the state,

which is why Lawrence said he wasn’t surprised Ives came so close to

Rauner during the primary. He said although most of the Republican

lawmakers around the state tend to be more moderate, they need to

deliver messages that resonate with both moderates and those more

right-leaning.

Lawrence

added that those who identify as more conservative are “dedicated

voters” who turn out more than moderates and independents during primary

elections. “What I think needs to happen is moderate Republicans and

independents need to become more engaged in the primary process,

particularly in the Republican primary,” Lawrence said. “Moderates, by

their nature, don’t have the passion that right-wing conservatives have.

They need to get more engaged candidates and their organizations need

to work harder at getting more voters engaged.”

Piecing the parts together

Rauner

would still have lost the election if it had been between just him and

Gov. J.B. Pritzker. Even if the votes from Conservative Party candidate

Sam McCann and Libertarian candidate Grayson "Kash" Jackson had gone to

Rauner (totaling 6.8 percent), Rauner still would have been shy of

winning the election by almost nine points. It can be argued that

Republicans in the state lost big because of Rauner, but Redfield and

Lawrence said it’s not that simple.

Rauner’s

failures aren’t the only thing that hurt Illinois Republicans in the

last election. Rauner may now be one less obstacle preventing

Republicans from winning districts in the state, but Republican leaders

need to find a collective voice and rebuild their platform if they want to

survive. If they can’t make change before it’s too late, the current

state of Illinois government – Democrats hold supermajorities and serve

as all five constitutional officers, including the governor – will

remain the future.

“I

think what binds us, or what can bind us in the future, is if we look to

our party platform, which was overwhelmingly approved by a majority of

active Republicans,” Ives said. “If we use that as our guideline on

policy issues, I think then, only then, we can come together as a

party.”

Republicans

around the state have been critical of Rauner, but they also don’t deny

there needs to be a more unified platform among their leaders. Ives said

a fragmented party is what cost Republicans the General Assembly seats

they lost in 2018. She also said many voters cast their ballot based on

emotion, not on policy issues. While it can’t be proven that emotions

are what gave Democrats the wins over their colleagues across the aisle,

it is a fact Democrats won in areas they hadn’t won in decades.

Redfield

said the rift between suburban and southern voters and their ideal

Republican candidate can also be seen in political action committees

like Liberty Principles PAC and Illinois Opportunity Society that

contributed millions of dollars in campaign financing against minority

leaders like state Rep. Jim Durkin and candidates he endorsed during the

2018 elections.

“You

want to have statewide leaders and a statewide presence,” Redfield said.

“You want united, effective caucuses in terms of the House and Senate

Republicans, and you’ve got these real identity issues and real

factions.”

One final

problem facing Republicans in future elections is the new trend of

selffinancing campaigns. It’s yet to be determined how Republicans are

going to proceed with financing the state party now that Rauner is out

of office.

“The fact

of the matter is, Republicans need to look at rebuilding their

organization that became far too dependent on Gov. Rauner’s money,”

Lawrence said. “It’s not going to be easy.”

Lawrence

said Republican leaders need to get back to the basics and engage

constituents all around the state to reconnect with voters. He thinks

it’s important that Republicans carefully consider who should run for

office, and he also agrees with Redfield that Republicans need to pay

attention to female voters if they want to win in the suburbs.

“Republicans need to capture the vote of suburban women, and it was clear in this last election that women

had a reaction to President Trump’s policies and his demeanor,” Lawrence

said. “It’s going to be difficult for Republicans to campaign in 2020

and distinguish themselves from policies and attitudes that turned off

key voters like suburban women.” To his point, the 21st, 24th and 27th

legislative districts, which have been Republican for decades, were won

by female Democrats.

Republicans

still have a place in Illinois politics, and many are intent on fixing

their image. Lawrence said Illinois voters are pragmatic, that they vote

more on policy issues, despite Ives’ claim to the contrary. While there

is disagreement on the underlying cause of the problem, both are aware

Republicans have work to do if they want to succeed.

Lawrence

believes it’s important for Illinois Republican leaders to try and be

viewed as a positive force in the state by voting and proposing

legislation that aligns with their principles; however, he said leaders

need to let voters see their willingness to reach across the aisle and

work with Democrats on policies when possible. He also said it’s

important for Republican candidates to revisit their relationship with

minority communities and demonstrate a sincere attempt to reach out by

showing up in their neighborhoods.

“People

of all races and ethnicities can identify whether people are sincerely

interested in them and reaching out to them in a sincere way, and

Republican candidates need to be doing that outreach,” Lawrence said.

Republicans

who are on a comeback mission still have time to regain their standing

in the state. Redfield said Republicans can take advantage of the next

few years when Democrats are in control of the Statehouse because the

party in power is walking a tightrope in terms of being close to a

fiscal disaster.

In

addition, Democrats are now facing the same problems Republicans had

over four years ago when Rauner self-funded his campaign. Redfield said

Democrats are also losing followers in southern Illinois who don’t agree

with some of the party’s progressive views.

He

added that Republicans may be able to win back some voters if Democrats

continue to propose and pass legislation that some independents and

moderate Republicans view as too progressive, like a $15 an hour minimum

wage.

“The success of Republicans is going to be relational to what Democrats do,” Redfield said.

Lindsey Salvatelli is an editorial intern with Illinois Times as part of the Public Affairs Reporting master’s degree program at University of Illinois Springfield. Contact her at intern@illinoistimes.com.