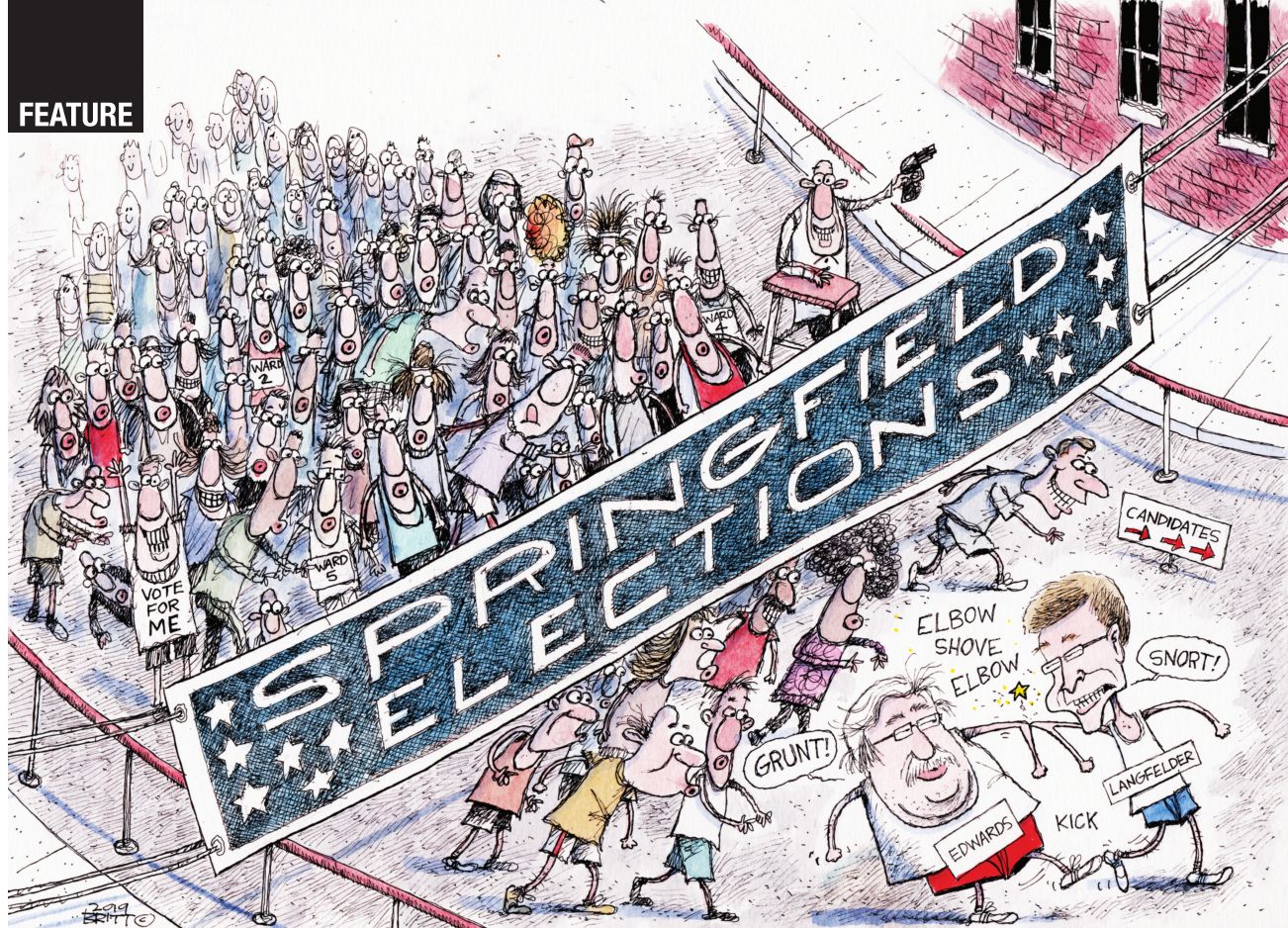

A crowded field for municipal races

If you think there are a lot of politicians on the make in Springfield, you’d be right.

Thirty-two candidates are vying for 13 municipal offices in the upcoming April 2 municipal election. Three citywide races – for mayor, city clerk and treasurer – each have two candidates apiece. Twenty-six candidates, the most in at least two decades, are running for city council, where just two of 10 races are uncontested.

“It’s a weird time – it really is,” says Brad Schaive, Laborers Local 477 business manager.

Ward 4 Ald. John Fulgenzi, who is facing three opponents, says he’s baffled by so many candidates. “I didn’t think I was doing that bad a job,” Fulgenzi says.

Despite the number of candidates, there will be no primary election, which is triggered when five candidates seek the same seat. The city clerk and the treasurer’s offices are essentially administrative posts, with the clerk keeping track of records and the treasurer keeping track of money. And so the mayor’s office and the city council is where the power lies and where just-plain-voters, as opposed to insiders, likely will be focusing attention.

“I don’t think he can win”

Mayor Jim Langfelder, the wise guys say, is a prohibitive favorite.

He’s affable, quick to smile and son of the late Ossie Langfelder, who served two terms as mayor before losing the 1995 mayoral primary. The mayor says and does seemingly unpopular things – his push for tax increases is a case in point – that haven’t seemed to dent his popularity. In 2015, he won his first mayoral term easily. Before that, he ran unopposed in two of his three campaigns for treasurer after winning his first term as treasurer by a wide margin.

During his first term as mayor, Langfelder has sometimes governed as if there were no consequences, angering organized labor, for example, after unions helped put him in office four years ago. He didn’t blink when police officers in 2017 declared that they had no confidence in police chief Kenny Winslow. Nearly 90 percent of officers who cast ballots said they had no confidence in the chief, but Langfelder’s support for Winslow hasn’t wavered.

Langfelder, a Democrat, also has been reluctant to endorse candidates, casting himself a nonpartisan politician – municipal races are officially nonpartisan, but parties have traditionally played

significant roles. He didn’t endorse J.B. Pritzker in the governor’s

race. He endorsed Betsy Dirksen Londrigan in the Democratic

congressional primary last year, but he didn’t lend his name to

Londrigan in the general election, which U.S. Rep. Rodney Davis,

R-Taylorville, won in a squeaker. Such reticence might help explain why

some Democrats are less than enthusiastic about the mayor.

The

mayor’s distance from from partisan politics is a departure from 1995,

when Langfelder lambasted fellow Democrats for not supporting his

father’s bid for a third term as mayor. Instead, local Democrats

supported another candidate, Michael Curran, who ended up losing to

Republican Karen Hasara in the general election. “If you’re like me, it

felt like someone ripped your heart out,” Langfelder told party members,

according to a 1995 story in the State Journal-Register, which

reported that the future mayor also told committeemen during the party

meeting that they should sign oaths vowing not to campaign for

Republicans and resign if they go back on their word.

On

the other side is Frank Edwards, who got walloped in his 2015 bid for

city treasurer by Misty Buscher, who had never before run for public

office. Edwards, by contrast, is a former city fire chief who won three

terms as an alderman and rose to the mayor’s office for four months in

2011 after the unexpected death of Mayor Tim Davlin, who committed

suicide within months of the mayoral election. In 2009, he had an

ever-so-brief run for governor, dropping out before the Republican

primary.

Edwards

attributes his 2015 defeat to not working hard enough. He says he won’t

make the same mistake this time. Langfelder, he insists, is vulnerable,

and he intends to make crime, taxes, economic development, utility rates

and population loss issues in his campaign. No one issue, he predicted,

will decide the contest. Rather, he said, a combination of things,

including the city’s recent purchase of the Sonrise Donut Shop sign

absent a clear plan for it, gives him a chance.

“Every

time something like that happens, it’s a chink in your armor,” Edwards

said. “If you get enough chinks in your armor, you’re vulnerable. … If

it gets into he’s a nice guy and I’m a nice guy, I lose – I know that.

If it comes down to issues-oriented leadership, he loses.”

That

Edwards is the lone challenger suggests that other potential candidates

thought Langfelder couldn’t be beaten. State Rep. Tim Butler,

R-Springfield, last fall acknowledged that he was considering a run, but

he didn’t try. Butch Elzea, a Republican businessman with name

recognition, also considered a run, but didn’t pull the trigger.

Sangamon County board member Tony DelGiorno, a Democrat, last fall

commissioned a poll aimed at determining who might have a chance of

unseating the mayor. The results have not been publicly released.

DelGiorno, who included his name in the poll, told State Journal-Register political writer Bernard Schoenburg that people feel the city isn’t “moving forward the way we should.”

Gail Simpson, a Democrat who’s running for the Ward 2 aldermanic seat, disagrees.

“I

believe he needs another chance,” Simpson says. “Maybe people feel,

like I do, that Langfelder hasn’t done a terrible job. He’s been open.

He’s been accessible. He’s been out in the community.”

At

times, the mayor sounds like a second term is a done deal, saying that

he’s planning on more individual meetings with aldermen, who’ve

criticized him for a lack of communication.

“I

think, going into the next term, I’ll probably try to do more

one-on-one meetings than I have with aldermen,” he says. Then again, he

says he won’t sit back.

“I’m not going to let the foot off the pedal,” he says. “We’re going to campaign as hard as ever.”

In

addition to proven popularity, there also is history. Mike Houston, who

finished third in the 2015 primary, is the only Springfield mayor since

1963 who hasn’t won two consecutive terms (Houston, however, won

successive terms when he served as mayor from 1979 to 1987).

Houston wouldn’t bet on Edwards. “I don’t think he can win,” the former mayor says.

Ward

2 Ald. Herman Senor, who is facing three opponents, said that Edwards, a

fellow Republican, has a chance. But the alderman sounded like a

football analyst assessing Cal Tech’s chances against Notre Dame.

“He’s

on the ballot, so there obviously is a chance for him,” Senor said. “It

goes back to how hard we as candidates work for our seats. So, yeah, he

has a chance.”

Wars of the wards

Theories differ on why so many people are running for city council.

On the one hand, it could be that people aren’t satisfied with city government.

“I

think, genuinely, people are looking at the representation and saying

perhaps we can do better – we need to do better in terms of what’s

happening with the city or in terms of what’s happening overall,”

Simpson posits.

Then

again, there are just two mayoral candidates, which suggests

satisfaction with Langfelder, who has more to say about the city’s

direction than anyone. Questions of plant-a-candidate have risen, thanks

to a November story by Schoenburg, who reported that the husband of

deputy mayor Bonnie Drew collected signatures on petitions to run

candidates against Ward 1 Ald. Chuck Redpath and Ward 6 Ald. Kristin

DiCenso. In Redpath’s case, he’s facing the Rev. T. Ray McJunkins, whom

he beat easily in 2015. DiCenso will face political newcomer Elizabeth

Jones. Bonnie Drew has denied any involvement with her husband’s

political activities, as did the mayor.

“I think there might have been some people recruited to run,” allows Schaive.

The

plot thickened when Anna Koeppel, a Democratic committee member,

unsuccessfully challenged Jones’ petitions, claiming that election dates

on documents were wrong and that Jones should be disqualified due to an

unpaid parking ticket. Koeppel is employed by the Laborers’

International Union of North America. Schaive, who heads the local

laborers union that supports DiCenso, who is a Republican, says he

played no role. “I have nothing to do with that whatsoever,” Schaive

said. “She (Koeppel) is a Democratic precinct committeeman. I’ve never

been to a precinct committeeman meeting, Republican or Democrat. I had

no discussions with her about that.”

Langfelder has an ally in Ward 7 Ald.

Joe

McMenamin, who’s been targeted by unions and whose campaign for a third

term may be the most interesting in the city. He says the mayor has

done an “acceptable” job and deserves another term. He’s blunt about

Edwards’ chances.

“It would be the upset of the half-century,” the alderman says.

If

Langfelder has coattails, McMenamin is grabbing them in his race

against Brad Carlson, a Capital Township trustee and chief of staff at

the state Department of Natural Resources. “I’m very pleased to have a

close relationship and close connection with Mayor Langfelder and the

department directors,” the alderman says. His colleagues on the council,

not so much.

McMenamin’s

relationship with other aldermen is strained to the point that council

members last year considered removing aldermen considered disruptive

from meetings if two-thirds of the council voted to have them taken out.

McMenamin – who’s exchanged sharp words with his colleagues for

accepting campaign contributions from political parties, labor and

vendors who do business with the city – isn’t backing down.

“The

question of who owns the candidate is extraordinarily important,” says

McMenamin, who boasts that he doesn’t take money from political parties,

unions or entities that do business with the city. “It’s a question of

character. Some aldermen are unwilling to vote in the city’s interest.”

What about Langfelder, who accepted union help during the 2015 campaign? That’s different, according to McMenamin.

“I’m

impressed that when Brad Schaive and the laborers (union) gave 20 grand

to Jim Langfelder, they acted like they owned him,” McMenamin says.

“Jim Langfelder has basically been a strong enough mayor to say no to

Brad Schaive on some issues, and I respect that.”

Schaive,

who’s had run-ins with Langfelder over city contracts that he feels

were either illegal or didn’t sufficiently benefit union members, paints

McMenamin as disingenuous for not taking the mayor to task for

accepting contributions from companies that do business with the city.

He makes no apologies for unions giving money to city politicians.

“That’s part of the political process,” Schaive says. “I personally

believe that every person, when you follow the law, you have a right to

be part of the political process.”

Houston

calls Ward 7 the most fascinating of the council contests, in part

because McMenamin has never had just one opponent and has never won a

majority of the vote in his three-way contests. Can he prevail in a

one-on-one race? “I think it will be a very competitive race,” Houston

says.

Carlson, who

enjoys support from unions, says McMenamin can’t be effective. “If he

can’t sit down with either business or labor or the other nine aldermen,

he’s doing somewhat a disservice to the residents of Ward 7,” says

Carlson, a Republican who calls himself a bipartisan candidate.

McMenamin

has blasted other aldermen for gathering at Saputo’s restaurant in 2017

to accept campaign contributions from unions and developers. There were

enough council members present to constitute a quorum, but aldermen who

attended the gathering said they discussed no city business and so

there was no violation of the state Open Meetings Act.

Was

the gathering appropriate? “That’s tough for me to answer,” Carlson

responds. “What happened there was legal, it was lawful – it’s all

(contributions were) reported on the state elections board website.”

What about the Open Meetings Act? “We’ve got to take them (aldermen) on

their word,” Carlson says.

Carlson

sees himself as the underdog – that, he says, is usually the case in a

oneon-one race against an incumbent. In any case, Ward 7 traditionally

has high turnouts for municipal elections. In 2015, it had, with 44

percent of voters casting ballots, the second-highest turnout of any

ward in the city, trailing only Ward 10, which had a 45 percent turnout.

And so running a campaign in Ward 7 could prove more expensive than in

other wards, where candidates will have fewer mailers to mail and fewer

voters to sway, presuming they concentrate on voters who’ve cast ballots

in past municipal elections.

The

flip side, when it comes to turnout, is Ward 2, where voters

historically have skipped municipal elections. Shawn Gregory, an

aldermanic candidate in Ward 2, says he’s hoping east side voters buck

history. “If we have a big turnout, you’ll talk to me again as an

alderman,” Gregory says. “I hope to inspire more than 1,800 people to

get involved in their community.”

Twenty

percent of registered voters in Ward 2 cast ballots in the 2015 general

election, dead last for turnout among the city’s 10 wards. Citywide

turnout was 34 percent. Gregory, a political newcomer, casts himself as

the fresh face in a four-candidate field that includes Senor, the

incumbent, Simpson, who was succeeded by Senor on the city council after

two terms as an alderman, and Tom Shafer, who’s run unsuccessfully for

several offices, including Springfield School District 186 board, the

Sangamon County Board, Sangamon County coroner and the Lincoln Land

Community College board of trustees.

Simpson

and Senor have accomplished little during their combined 12 years on

the city council, Gregory says. While low turnouts can favor incumbents,

Senor, a Republican who lost a bid for state representative last fall,

says he’s hoping that high turnouts for the November general election

will carry over to the Ward 2 aldermanic race. Low turnouts in the past

might be attributable to transportation issues and older folks not being

able to make it to the polls, he said.

“Who knows why people don’t want to participate?” Senor said. “You can take the horse to water, but you can’t make it drink.”

With

four candidates in the race, Senor says he doesn’t expect to win a

majority, but 36 or 37 percent is a reasonable target. Experience, he

says, counts, and while every candidate says that drawing new business

to Ward 2 is important, it isn’t easy.

“I’ve

been here for three and three-quarters years and finally got myself

established,” Senor says. “I kind of think before I act. Some of these

things take some thinking.”

Simpson,

who gave up her aldermanic seat in 2015 to run for mayor, said she

decided to run for her old seat in part because Senor, the incumbent,

was running for the legislature. “Nobody, including myself, could have

waited for the result of the state race,” she says. She said she chose

to run for mayor four years ago out of frustration that the city wasn’t

paying sufficient attention to Ward 2, and east side residents share her

frustration and have grown cynical about city politics and government.

“I had people say to me, ‘What difference does it make?’” Simpson said.

“They’re not going to vote because they don’t see change.”

The

Ward 5 in the city’s north end also pits a former alderman against an

incumbent, with a Capital Township trustee thrown into the mix. Thanks

to the growing popularity of early voting, the race essentially will be

over by election day, predicts LaKeisha Purchase, who in 2017 became the

first Democrat to win a seat on the township board in 40 years.

Purchase

rejects the notion that she and Sam Cahnman, a fellow Democrat, will

split votes and hand the election to incumbent Andrew Proctor, who

easily beat Cahnman four years ago. Municipal races, she says, hinge on

the person, not the party, and there may be some truth to that. After

all, Senor, a Republican, handily won the Ward 2 race in 2015 even as

Langfelder, a Democrat, carried the ward by a wide margin. Still,

Purchase acknowledges she’s heard the talk.

“I’ve

had multiple people come to me and say ‘You’re probably going to lose

because Sam’s in the race and there’s two Democrats,” Purchase says.

Cahnman, an attorney, has baggage.

His

loss four years ago came after he was censured by the Illinois Supreme

Court for misrepresenting how he had obtained a copy of a judge’s work

calendar. In 2002, he was temporarily banned from the county jail after

guards reported seeing him kiss and embrace a prisoner. In 2009, he was

arrested for allegedly soliciting sex from police officers posing as

prostitutes, but was acquitted of a misdemeanor charge. In 2011, a woman

called police, saying she woke up without her underwear after going to

Cahnman’s apartment and drinking wine; no charges were filed. Two years

ago, his law license was suspended for 90 days after the state Supreme

Court found that he had represented Calvin Christian III in traffic

cases without disclosing his representation to the city council. At the

time, Christian was suing the city for failing to produce disciplinary

records of officers who’d cited him for traffic offenses. It might not

matter – after all, Cahnman has won past elections despite unsavory

headlines.

Cahnman says math is in his favor.

“Theoretically,

if I get the same number of votes I got four years ago, that would be

enough to win a three-way race,” he says. A precinct committeeman

campaign last spring also bodes well, he said. Initially, he said he was

disappointed that he drew opposition, but he got 70 percent of the

vote.

Proctor, who has won labor’s support, says he’s focused on his campaign, not the opposition.

“I’m not going to speculate on the motives of the other two candidates,” Proctor said.

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].