Springfield’s 1908 fires continue to smolder

“Whites have often feared that greater freedom for others necessarily implies a loss for themselves” – Michael Cassity, Chains of Fear (1984)

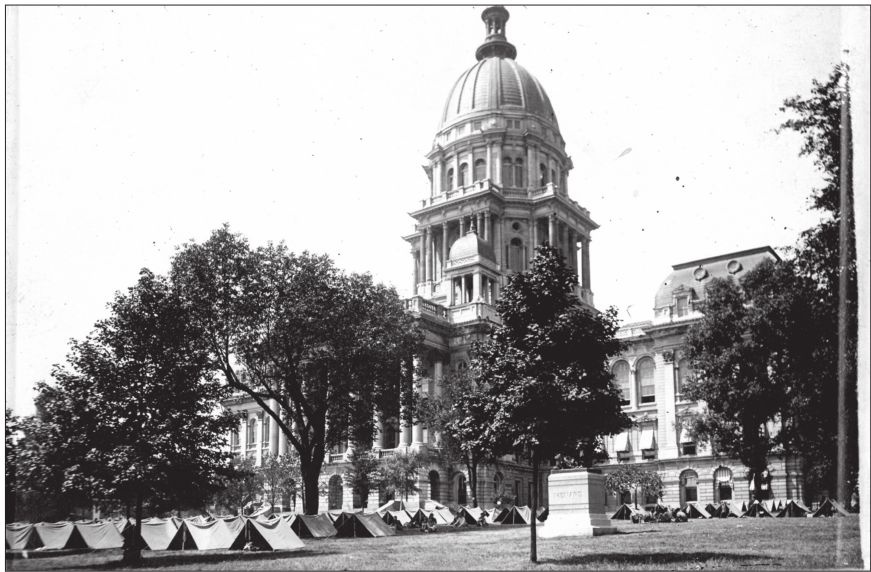

In recent weeks, much area media attention has been focused on the 110 th anniversary of the mid-August, 1908, race riot in which 5,000 white Springfield citizens were responsible for lynching two black men, driving 2,000 black people from their homes and doing $150,000 in property damage ($4 million adjusted for today) resulting in only one conviction for a rioter – for petty larceny in the theft of a sword. Articles, film screenings and museum exhibits this week shone a light on this ugly chapter of Springfield’s history which many would find it convenient to forget or ignore. The riot memorials coincidentally arrived on the same week as the one-year anniversary of the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia – during which Heather Heyer was killed by a white nationalist who crashed his car into a crowd of peaceful protesters. So it seems important to question just how far we have come as a society since 1908.

“I have experienced, certainly, the vestiges of the race riot, the kind of attitude that led to it and that I believe still persists today,” said Dr. W.G. Robinson-McNeese, system executive director for diversity initiatives at Southern Illinois University. “One thing that still exists is the belief in the inferiority of the black person – which predated the riot and is still present. I see it all the time where people still think of folks with my background as being inferior, and they walk that out in many different ways in our society.”

McNeese said that working in a prominent position within the SIU system, he still often finds himself left out of meetings and committees. “I don’t always have a seat at the table and I don’t necessarily always know what’s going on because I haven’t been included,” he said. “It seems that my opinion isn’t important enough to be on this committee or that committee. I see that over and over again. It’s as if they’re saying, ‘We don’t have to worry about Wes and what he’s thinking’ or that I might even represent an alternative opinion.”

Even in his long career as a medical doctor, McNeese perceives significant evidence of racial bias. “I find other physicians who do the same work I do often make much more money than I do,” he observed. “You see differences in pay, in title, in the way that you’re treated. Do you know that only five percent of the physicians in the U.S. are African-American? And here’s what is astonishing – 50 years ago it was also five percent.” McNeese believes that these figures are the result of deliberately maintained systemic barriers. “I don’t believe it is because you have that few people who want to be physicians. The system has built-in bridges and hurdles to prevent them from getting in, which is atrocious.”

Tellingly, while the initial impetuses for the 1908 riot were a rape charge leveled against George Richardson (later recanted) and a murder accusation against Joe James (who was eventually hanged), both poor black men, the main targets of violence during the riot were the homes and businesses of Springfield’s more affluent, law-abiding black citizens. According to Roberta Senechal de la Roche in her book In Lincoln’s Shadow: The 1908 Race Riot in Springfield, Illinois, “some Springfield blacks had violated their subordinate place in society by openly expressing higher aspirations and by actually achieving a modest measure of power and material success.” At the time, there were black Springfieldians who had won recognition in city politics, some who owned businesses and were homeowners. Black votes in general were both courted and rewarded. “During the riot, the deviant character of this black progress was demonstrated by the selection of black achievers as prime targets of the attack,” Senechal de la Roche reported.

“There is evidence that the mob was not after the worst Negroes so much as they were after the best,” wrote author Mary White Ovington in The Walls Came Tumbling Down (1957), quoting a contemporaneous black newspaper editor responding to news coverage of Atlanta’s 1906 race riot. “The shiftless, irresponsible and ignorant whites who make up

the mob and spread the mob spirit are constantly picking quarrels with

enterprising Negroes in order that they may have some excuse for

carrying out the dictates of depraved and lawless ambition.”

McNeese,

who was raised in East St. Louis, often walks around the downtown

Springfield areas where the riot took place. “I see the Horace Mann

building, which is where the Levy was – the area where the black

businesses had been before the riot – and I wonder if the owners of that

company even know that is the history of that area and how it has been

reclaimed. Whites in this city – just like in my hometown, when they

rioted – felt like blacks were doing a little too well, getting out of

their places and that had to be stopped.”

Violence

in the 1908 riot also extended to prominent white citizens who were

seen as being overly sympathetic to the black population. Prominent

white restaurant owner and National Guardsman Harry Loper was known to

have black employees and played a part in helping law enforcement move

the incarcerated suspects, Richardson and James, from Springfield to the

jailhouse in Bloomington in order to save them from the growing lynch

mob which would eventually swell into the riot.

The

subsequent targeted destruction of Loper’s popular and elegant

restaurant at Fifth and Monroe was in revenge for its white owner

helping the sheriff move the black prisoners – thereby saving them from

the mob.

The

subsequent targeted destruction of Loper’s popular and elegant

restaurant at Fifth and Monroe was in revenge for its white owner

helping the sheriff move the black prisoners – thereby saving them from

the mob.

This

was, according to Senechal de la Roche, “but one expression of what

rioters thought of whites who valued law and order over the enforcement

of black subordination.” After the riot, the city became a symbol of

white rage, with reports of subsequent lynch mobs in other cities

shouting “Give ’em Springfield!” to menace their targets.

“As

a black man today, I have many white friends,” McNeese mused. “But I

sometimes wonder, if push came to shove and I was the person being

rioted upon, would they stand by and watch or would they intervene?” The

Springfield Coalition on Dismantling Racism (SCoDR), which describes

itself as “a community organization that brings antiracism training to

Springfield,” sponsored a gathering Aug. 15 at the Preston Jackson

sculpture in Union Square Park, with the goal of examining the 1908 riot

from a contemporary perspective. “If you don’t know your history,

you’re doomed to repeat it,” said Sister Mary Jean Traeger of SCoDR. “We

are talking about some of the experiences of racism that continue today

in different ways.

The

training itself I think has been very effective. Not everybody goes

away saying, ‘OK, I’m not going to be a racist anymore,’ because that

isn’t possible anyway. I think because of what’s happening in the

community – not just Springfield but beyond – more and more people are

realizing they have to have some help.”

“Attending

antiracism training gives us all a common language,” said McNeese, who

has attended at least five of the antiracism training sessions hosted by

SCoDR and administered by national antiracism organization Crossroads.

“The word ‘racism’ might mean different things to you than it does to

me. But when you attend training, suddenly we are speaking a common

language about the definition of racism. I think you need to have a common language even to have a good conversation about such a difficult topic.”

Traeger

says that the trainings have worked well but that personal success

stories in overcoming racism are less important than systemic ones. “The

Dominican Sisters have been doing this for 13 years,” she recounted.

“At the beginning, as an all-white congregation, the first thing we

wanted to do was change ourselves.

So

we invited people of color that we knew and had relationships with to

be part of our team. We now have 50 percent people of color and 50

percent white people whenever we meet, which is ongoing. SCoDR came out

of that.”

If anything

positive can be said to have resulted from the 1908 riot, it would

probably be the formation of the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

The

riot received a great deal of attention in the national press at the

time, particularly the widely read article “A Race War in the North” by

journalist William English Walling, published in the North Carolina

weekly newspaper, The Independent. The reporting of Walling, who

traveled from Chicago to witness the riot firsthand, sounded an alarm

that racial violence in the early 20 th century was not strictly a

southern problem, as had been widely believed.

Interviews

conducted by Walling with Springfield whites in the aftermath of the

violence largely amounted to a noncommittal “something was bound to

happen” attitude, with upward mobility of blacks seen as the primary

motivation (“Why the [blacks] came to think they were as good as we

are!”). Walling’s story and others like it culminated in

the formation of the NAACP by African- American leaders W. E. B. Du

Bois, Ida B. Wells, Archibald Grimké and Mary Church Terrell, along with

white allies Henry Moskowitz, Mary White Ovington, Florence Kelley and

Walling himself. Historian James L. Crouthamel said that the NAACP was

“not able to prevent…race violence…but it could focus national attention

on these incidents, point the fingers of scorn and bring negro

discontent into the open.” Crouthemel concluded that “had the

Springfield race riot not occurred…at a place where the Lincoln aura was

the strongest, the NAACP might not have been established.”

“When

I think about that absence of civility, or the comfortableness that

people have now with expressing their bigotry, it is of great concern to

me,” said McNeese, regarding the recent mainstreaming of white

nationalism. “I listen to the radio reports reminding us of what

happened in Charlottesville and feel that could easily happen here in

Springfield.” McNeese believes that he sees the kinds of attitudes that

fueled the 1908 riot in people he meets on a daily basis. “Not

everybody,” he said, “but every now and then I see the way someone

reacts to me or the way they treat me and you know that this is a person

who just might hurt you, given the right set of circumstances. I

recognize that those ideas are not moribund, they are just under the

surface.”

When asked

what people might do to counteract these sorts of attitudes, McNeese

says that after establishing a common language, as happens in the SCoDR

training sessions, the next step is to try to make yourself an

ambassador for antiracism. “A lot of us will never have the opportunity

to affect the masses, but we can affect the people next door and who we

work with. I think it has to happen almost at the grass-roots level,”

McNeese said. “It is a long haul to change people’s attitudes – it’s

really one person at a time.”

Scott Faingold can be reached at [email protected].