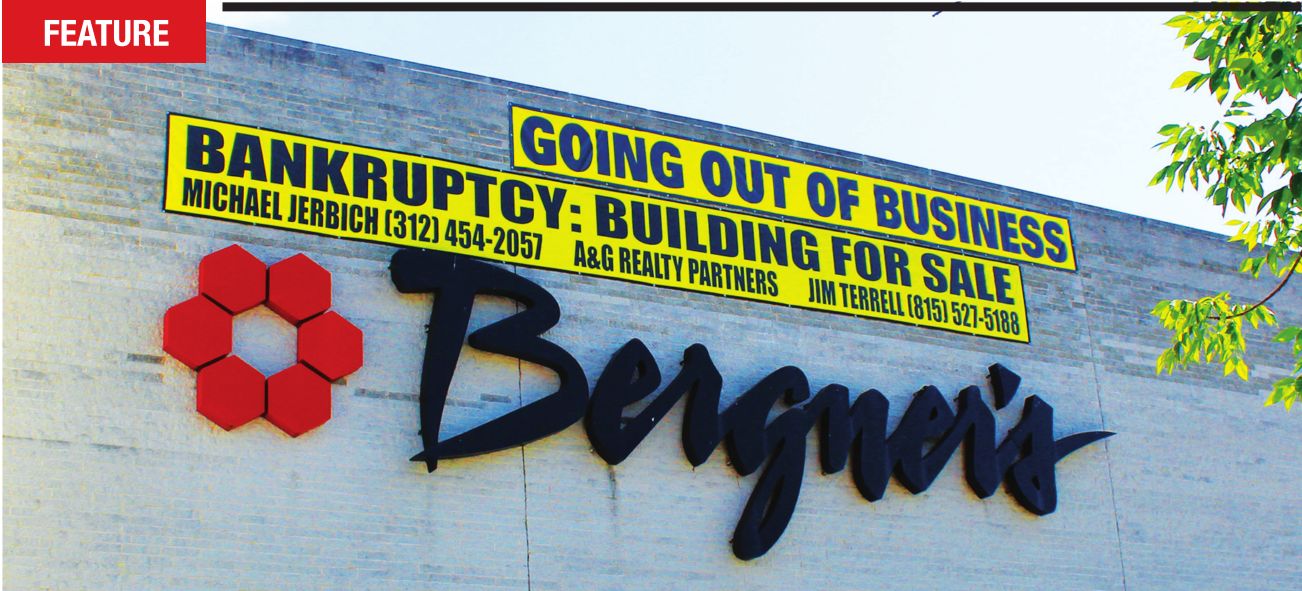

Bergner’s, Sears are shutting down

With the corporate parent of Bergner’s declaring bankruptcy and Sears struggling, two of the city’s oldest and largest department stores, both in White Oaks Mall, are shutting down.

But the death of the department store – or the mall itself – can be much exaggerated.

“From a 30,000-foot perspective, I know, for people in Springfield, it looks a little bit scary to lose two large anchors like that,” Clay Emerich, White Oaks manager, told the Springfield City Council last week during what might best be described as a state-of-the-mall presentation.

It’s not just a matter of losing places where you can shop for dishwashers, pick up a pair of jeans, consider coffee makers and ponder a new set of dinner plates, all while getting the oil changed on your car. For the city, it’s a matter of money.

Sears and Bergner’s together hold down 125,000 square feet of retail space on some of the most lucrative land in a city that balances its books on sales taxes. Sales taxes paid by businesses aren’t matters of public record, but even before a nickel in sales tax is generated, Bergner’s, which owns its store, pays more than $75,000 a year in property taxes; Sears, which owns both retail space and adjacent parking areas, pays more than $180,000 on nearly 14 acres, acording to Sangamon County property records.

It is space that Indiana-based Simon Properties, owner of White Oaks, perhaps naturally, covets, given that Bergner’s and Sears are co-joined to the mall. “From conversations I’ve had with executives at Simon, they’re being very, very aggressive right now in acquiring that space,” Emerich told the council. “The bottom line is, we’re very, very excited to have the opportunity to have both those spaces back. … I can’t stress it enough: Losing those two anchors, really, is a wonderful, wonderful thing for us.”

Excited? Opportunity? Wonderful thing?

For the casual observer, “terrified” might seem a more appropriate term, given the continued rise of online shopping amid failures of such retail giants as Toys R Us and H.H. Gregg. Nationwide, brick-and-mortar retailers filed for bankruptcy at a record rate last year, and the trend continues, with loan defaults among retailers reaching an all-time high during the first quarter of 2018, according to Moody’s Investor Services.

Department stores and mall-centric retailers seem particularly at risk, with such companies as Neiman Marcus, Sears, J.C. Penney’s and J. Crew struggling to survive. Simon Properties, the nation’s largest owner of mall properties, has diversified at malls throughout the country, replacing stores with hotels, office space, restaurants and condominiums. To some extent, such changes already have happened at White Oaks. After the mall’s cinema closed in 2008, a church briefly took over before the space was renovated to make way for restaurants and retail shops. L.A. Fitness in 2013 opened in space once occupied by Montgomery Ward.

Springfield already has survived a Simon sell-off of properties. As the Great Recession took hold a decade ago, the company dumped malls with poor sales and prospects, then reinvested in the remaining portfolio, including White Oaks, which got a makeover in 2012 that cost more than $6 million. New carpet and tile were laid. The food court was spiffied up. The merry-go-round was replaced with a better merry-go-round. Six years later, challenges remain.

Emerich told the council that foot traffic has fallen “pretty precipitously” during the past four years, and the mall is heavy on purveyors of apparel. The mall wants to attract entertainment, restaurants and service industries, he said. “We believe we can offer Springfield exactly what it needs,” Emerich said. “We believe that in the next three to five years, we will be in that position once again, where we can be...the premier mall for all of Springfield and surrounding communities and keep those dollars here in the Springfield area.”

The mall, Emerich said, hopes to lure shoppers from Peoria, where Macy’s closed two years ago at Northwoods Mall, which is also owned by Simon Properties, and there is no need to worry about prospects in Springfield. “All things are very, very secure with White Oaks at this time,” Emerich said.

Sears has long been in a well-publicized tailspin, and so the closure of the company’s store at White Oaks wasn’t a surprise, Emerich said. The end of Bergner’s, whose parent company Bon-Ton Stores filed for bankruptcy in February, was a different matter.

“We weren’t expecting Bergner’s,” Emerich told the council But no big deal, according to David Simon, chief executive officer of Simon Properties, who labeled the Bon-Ton bankruptcy a “nonmaterial event” during a quarterly conference call with stock analysts in April. “We’ve already got users (for the space) identified,” said Simon, who is known for dismissing retailer bankruptcies as a fact of life. Simon didn’t say when space now occupied by Bergner’s and other Bon-Ton stores might be turned over to different tenants, and he didn’t specifically address White Oaks or Springfield, but the bankrupt company won’t formally surrender spaces in Simon malls until the third quarter of this year. Overall, he acknowledged, occupancy rates are down, but prospects are up, no matter what naysayers might predict.

“Our

business always recycles itself, it’s done so for a long time,” Simon

told analysts. “Our product has been around for 70 years. … (T)he media

wants this one narrative, but it’s just not reality. And look at our

numbers, OK? We’re going to make $4 billion this year, OK? It’s not

perfect. … I’d like not to have a slight decrease in occupancy and this

and that and the other. But we’re in good shape.”

In Springfield, Ward 7 Ald.

Joe

McMenamin has faith. He notes that Simon has installed such

nontraditional uses as senior living centers at other properties, and he

foresees law offices, accounting firms and other businesses aside from

retail and restaurants moving into White Oaks.

“If

they locate at White Oaks, they’ve got an advantage with the pubic in

terms of the public knowing where to go and knowing there will be enough

parking,” said McMenamin, whose ward includes the mall. “Historically,

White Oaks Mall and perimeter space are the number one real estate and

sales tax producers within city limits.”

Emerich

invited questions at the end of a presentation lasting less than six

minutes – it was, McMenamin says, the first instance he can recall of a

White Oaks manager addressing the city council.

“I

know there’s probably a lot of questions surrounding direction, where

we’re at, where we’re going, with the recent news about Bergner’s and

Sears,” Emerich told the council. But there were no questions from

aldermen.

Not all

stores are failing City budget director Bill McCarty said he doesn’t

foresee immediate disaster in the demise of Bergner’s and Sears. “We

still have Kohl’s, we still have J.C. Penney’s, we still have Macy’s,”

notes McCarty, ticking down the list of survivors. “I firmly believe

it’s not necessarily going to impact sales taxes directly.”

Still,

the city, which relies heavily on sales taxes to make ends meet, has a

long-term issue, with sales tax collections in decline as online

shopping gains popularity while the city’s population drops. Turning

retail space into gyms might help Simon’s bottom line while also

creating healthier bottoms, but city coffers aren’t swelled because

sales taxes don’t apply to gym memberships, weightlifting classes or

other services in Illinois.

“We have a relatively narrow tax base,” McCarty says.

Not

all department stores are failing, but it has been a roller coaster for

some in recent years. Macy’s stock, for example, plummeted to less than

$6 a share during the 2008 recession and closed at nearly $40 earlier

this week. In between was a rise that peaked at nearly $70 per share in

2015, then a tumble that bottomed out at $20 in November, meaning that

anyone who invested last Thanksgiving would have nearly doubled their

money. Kohl’s stock has seen severe fluctuations in the past decade but

has proven a good investment, nearly doubling in value during the past

year. Dillard’s and Nordstrom, neither of which have stores in

Springfield, also have proven resilient.

And then there is J.C.

Penney’s,

heavily leveraged with a steadily plummeting stock price, and Sears,

which has been selling off brands and real estate while closing stores

in desperate attempts to stay afloat. In both cases, analysts have

speculated about chances for bankruptcy.

It is no exaggeration to say that Springfield’s department stores aren’t what they once were.

During

a January visit to Sears, a store I hadn’t visited for years, for an

oil change, I was stunned by the empty shelves and empty sales floors.

In the hardware department, there was more vacant pegboard than hanging

tools on display, although signs – still present during a visit after

the store’s impending closure announced last month – promised that a

new-and-improved tool section was on its way.

Throughout

the store, both clerks and shoppers were scarce to the point that it

felt like a “Twilight Zone” episode, where everyone has been either

obliterated in a nuclear attack or kidnapped by aliens and only the

protagonist remains. There were more people during a visit this month,

after the going-outof-business sale was announced, but it wasn’t close

to a stampede on the day I checked in. Still there were lots of

appliances and garden equipment and shoes and sheets and other stuff to

be had at what seemed like decent prices.

Bergner’s,

more than a month into its liquidation sale, also was calm. The best

buys I spotted were pairs of Waterford crystal champagne flutes for less

than $100 and Keurig coffee, which a hooked-on-Keurig friend confirmed

was attractively priced at $13.50 for the 18-count box, marked down from

$22.50. Needing neither coffee nor champagne flutes, I resolved to return later in hopes of finding steeper discounts on bedding and silverware.

They

had a lot more stuff – furniture, clothing, cookware, towels, gizmos of

all shapes and sizes – that sucked in tire-kickers like me, and nearly

an hour spent wandering the sales floors felt like 20 minutes. Signs

promising between 40 and 60 percent off were undercut by a paucity of

price tags, and so I felt somewhat a bottom feeder as I toted items to

clerks standing at checkout stations to ask “How much?” It didn’t used

to be this way.

The

golden years Back in the day, Springfield was crammed with department

stores that eschewed door-buster sales when they opened or expanded.

Instead, stores held receptions, where the public was invited to visit

and gaze but not buy until the following day, when the store would open

in earnest. And there were plenty of stores. Bressmer’s. Myers Brothers.

Sears. J.C. Penney’s. S.A. Barker. R.F. Herndon and Co. Westenberger’s.

Springfield’s

first one-stopshop dry goods stores opened in the 1860s – R. F. Herndon

and Co. on St. Patrick’s Day in 1866, Bressmer’s in 1864, although it

didn’t acquire the Bressmer name until 1868, after John Bressmer, a

German immigrant, gained control. Others followed, and competition was

fierce.

“The children

of Springfield and neighboring towns need have no fear of being deprived

of imported toys this Christmas,” the manager of R.F. Herndon’s toy

department, recently returned from a buying trip to New York, told the Auburn Citizen in

August 1914, shortly after World War I broke out. “Already, several

cases of toys have arrived, and I was able to secure toys made in

Germany and other belligerent countries before the war was declared and

before American jobbers raised the prices on account of their inability

to get new toys this year.” And so Springfield was made safe for Santa,

if not democracy.

Herndon

once had three stores in Springfield, including locations downtown, at

Town and Country shopping center on MacArthur Boulevard and, of course,

at White Oaks Mall. The downtown store, as well as the Town and Country

location, closed in the late 1970s, shortly after the mall store opened.

Herndon’s went out of business entirely in 1997.

Featuring

both dressmaking and fabric departments, Springfield’s best department

stores once allowed shoppers to pick out cloth, then have it sewn into

gowns. Purchases were wrapped before leaving the premises, and banker

hours were de rigueur, with stores opening at 9:30 a.m. or so and

closing at dinner time.

The

Great Depression couldn’t stop Springfield’s love affair with

department stores. Sears opened at 621 E. Adams Street in June 1929, at

the cusp of the biggest economic catastrophe in U.S. history, and

expanded by 50 percent in 1936 before moving to Second Street and South

Grand Avenue in 1951 and, ultimately, White Oaks Mall. Montgomery Ward

arrived in 1934 on the 200 block of South Fourth Street, with the Illinois State Journal reporting

that spending money never had been so easy. “National Cash registers

are placed throughout the store, conveniently located, enabling the

salespeople to complete all transactions with the slightest amount of

delay to the busy shopper,” the Journal reported.

At

some point, Montgomery Ward moved to Adams Street before closing in

1966, only to reopen in 1977, when White Oaks Mall opened and the store

took up residence in what was then the brightest retail spot in town,

with such celebrities as Ed McMahon, Billy Carter and Bobby Riggs

present at the mall’s opening ceremonies. Montgomery Ward declared

bankruptcy in 2000, and the White Oaks store closed the following year.

Montgomery

Ward was just part of the herd as downtown department stores migrated

to the mall during the late 1970s. J.C. Penney, which opened in 1928 in

downtown, was an exception, moving to its present location on Dirksen

Parkway in 1971. But others couldn’t resist the siren call of the west

side.

Myers Brothers,

which was bought in 1968 by Phillips-Van Heusen, was the biggest and

most legendary. Offering everything from furniture to hats and featuring

a caged monkey named Weegee in its boy’s clothing department during the

1950s, Myers Brothers – the store that quality built, according to its

advertising department – once controlled an entire block on Washington

Street between Fourth and Fifth streets and had outlets in Jacksonville,

Lincoln, Havana and Mattoon. Even today, the Myers Brothers label is

common in local thrift stores, a testament to the quality of sport coats

made from Harris Tweed and heavy winter overcoats weighing several

pounds.

Fire couldn’t

stop the Myers family that started the store and ran it for more than a

century, even after the 1968 sale to Phillips-Van Heusen, a men’s

clothing company. When a 1924 blaze destroyed the five-story store at

Fifth and Washington streets, Albert, Louis and Julius Myers – brothers,

of course – instantly bought out a nearby store, building and contents,

and were open for business even while rubble smoldered. A new building,

twice as tall as the one destroyed by fire, was dedicated in 1925, with

just one day of business lost.

Myers

Brothers became Bergner’s in 1983, five years after Phillips-Van Heusen

sold it. The mall location opened in 1978, the downtown store went out

of business in 1989. Bergner’s survived bankruptcy once, with the

company emerging from Chapter 11 in 1993 under a new name, Carson Pirie

Scott, although the company’s 14 stores in Illinois continued operating

under the Bergner’s name. Bergner’s and its parent company were sold to

Bon-Ton in 2006 as part of a $1.1 billion deal that involved more than

140 stores purchased with borrowed money. Former Bon-Ton CEO Tim

Grumbacher defended the borrowing in a recent Wall Street Journal interview.

The problem, Grumbacher told the paper, was an inability to think

differently and become something other than a traditional department

store.

“It would have taken an imagination that wasn’t there,” he said.

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].