As a basketball player, Heather Moore didn’t fit the mold.

Chiefly, she was too short and too slight – vintage media guides from High Point University in North Carolina, her alma mater, list her at five foot six. In middle school, she played at south of five feet, and her coach told her that she’d never make it as a college player.

“I was a tiny, scrawny little thing, and people wondered why I wanted to play the game,” Moore told the Greensboro News and Record during her senior year in 1993. “They told me I’d never be big enough to play when I got to college.”

Moore proved big enough. A quarter-century after her senior year, she remains third on the alltime assists list at High Point, where she recorded 448 dishes during her collegiate career. Her reluctance to shoot was fierce – during her college career, she said she could still hear her mother and high school coach screaming at her to shoot when she was open.

“I’d only shoot if the option to pass wasn’t there,” she told the News and Record during her final season in college. “I hated to think about missing a shot. I guess I’m too much of a perfectionist.”

Shelly Whitaker Barnes, a college teammate, remembers the pass she got, if not the opposing team, after Moore stole the ball and led the break. “The defense was playing her well,” recalls Barnes, who is now athletic director and director of student support at Lenoir Community College in North Carolina. “I was tailing her. She went between the legs, completely nonchalant. It wasn’t for show, it was just a great pass. You don’t see that, or you didn’t see that back then.”

Beyond the ability to go behind the back and between the legs and otherwise make “crazy passes,” Moore, Barnes recalls, was both selfless and driven. “She’d come to practice with the intention of not only getting better herself, but making the team better,” Barnes says. “You never had to worry about pushing Heather.”

Barnes lost touch with Moore after college, but she isn’t shocked to hear that her former teammate has just been named a division chief of the Springfield Fire Department, which makes her the highest-ranking woman ever in a department that’s dominated by men, like many other municipal fire departments across the nation.

“I can’t say I ever imagined her doing that, but I’m not at all surprised,” Barnes said. “She’s such a hard worker and such a go-getter – it’s right in with her personality.”

“She’s a firefighter”

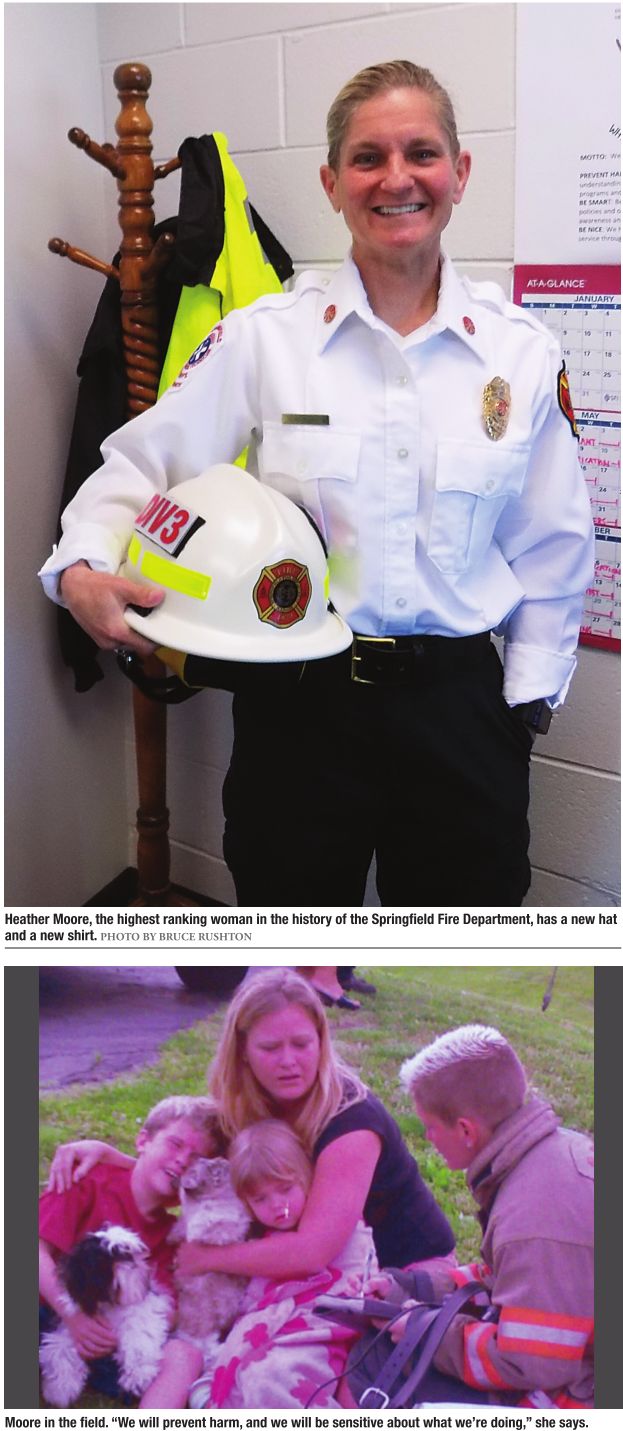

Less than three weeks into her new job as chief of the department’s training division, Moore has at least one adjustment to make: Her white command shirt fits like a tent, evidence that the department didn’t have a person of her dimensions in mind the last time shirts for toptier staff were ordered. For now, she’s making do with just one shirt, rolling up the cuffs and learning the benefits of Shout! stain remover to guard against ring around the collar.

“It might stand on its own by the time I’m done with it,” she says.

Moore

says she got emotional when she recently visited Station One downtown

to pick up her firefighting pants and coat and other gear that had

protected her from risks she no longer will face. She will, she says,

miss pulling ceiling, a cruddy-sounding job that is exactly what the

name suggests: Taking down ceilings with a metal hook to search for

fire. “Oh, it’s great,” she insists. “I love physical labor.”

It’s

an attitude not lost on Mayor Jim Langfelder, who interviewed Moore

about becoming fire chief before settling on Allen Reyne, who was

promoted to the job after former Chief Barry Helmerichs retired in

April.

“It’s pretty clear, she’s a firefighter,” the mayor says.

Reyne,

who promoted Moore from captain after becoming chief last month, says

that she has sufficient chops to rise as high as she likes in the fire

department. Moore dismisses the notion when asked if she’d like to be

chief. “I can’t see that,” she says. “I’m where I’m supposed to be.”

Then

again, Moore professes admiration for the military. The armed forces,

she says, promote core values and accountability. “I very much think I

would have thrived in the military,” she says. “They know who they are.”

Call

it karma, destiny or just plain luck, but Moore’s 1996 arrival in

Springfield was not a given. During college, she thought about working

as an insurance claims adjuster. After graduating cum laude from

High Point University with a degree in history, she came to Springfield

to be with a woman and work at Aldi’s, where she was on track to become a

manager. Neither the relationship nor a career selling groceries panned

out. But Aldi’s proved auspicious. A co-worker’s husband worked for the

Springfield Fire Department. Maybe, she suggested to Moore, you should

take the entrance exam. She did. She passed. And she excelled.

Just

six years after becoming a firefighter in 2000, Moore was teaching

others at the state fire academy in Champaign, where she’s been an

instructor since 2006. If you ever are trapped in a collapsed trench and

someone calls the fire department, there’s a good chance that Moore

will be there with you, at least in published form. She, quite

literally, wrote the book on how to accomplish trench rescues, with The Trench Rescue Technician Student Field Guide coming in pocket size for easy reference while in the field.

Moore’s

book includes drawings and photos and Occupational Safety and Health

Administration data and detailed instructions for dealing with trenches

of all sorts, and there are more sorts, it turns out, than a layperson

might imagine. She wrote it without benefit of ever actually saving

someone trapped beneath the earth; what she lacked in experience, she

made up with research on how to dig without having a trench collapse on

rescuers. “It’s like putting puzzle pieces together, having to figure

out a shoring system,” she says. “I’m curious. If you have to teach

something, you’d better know what you’re talking about. … It’s always

been a part of me – I’ve always been curious. That’s been an integral

part of my survival.”

Despite

a dozen years teaching at the state academy and her status as chief of

training for the department, Moore says she’s not comfortable in front

of a classroom. “It isn’t easy,” she says. “I’m very much an introvert.”

You wouldn’t know it, according to one firefighter who asked that his

name not be used.

“I’ve

worked with her, I’ve worked for her, not on a steady basis, but enough

to see she can be very, very personable, yet be very, very

professional,” the firefighter says. “She’s got no problem grabbing you

by the ear, pulling you outside and telling you what you did wrong. This

is the honest to God truth: The only person who’s going to bitch about

her is the person who doesn’t want to work hard and better themselves.”

There

is no training course that covers everything that can happen in the

field, and so the ability to MacGyver solutions is crucial.

Moore, point guard that she

once was, is a master of improvisation. “She’s going to find a way to

cheat, steal and borrow to get the job done,” the firefighter says. “You

get in certain situations where, sometimes, some people get tunnel

vision. Not her. She’s looking at the whole world around a problem.”

Sometimes,

it’s a matter of sheer determination. The firefighter recalls Moore

pulling him across a concrete floor, with both of them in full gear,

during a rescue drill aimed at teaching firefighters how to save fallen

colleagues. The procedure required her to lay on his back, put her arms

through his armpits and pull him along as she crawled. “I’m 240 pounds,”

he says. “The fact of the matter is, she’s basically force-crawling

with someone twice her weight, which is pretty impressive.”

Strictly

from an economic standpoint, it’s a good job, with the department’s

average salary last year exceeding $79,000, nearly $5,000 more than in

the police department. Division chiefs with 9-5 jobs make more than

$120,000. For others, the work schedule – 24 hours on duty followed by

48 hours of time off – allows firefighters to supplement incomes with

second jobs and commute just three days a week, and so it is easy for

those who enjoy country living to reside far outside Springfield. There

are just five women on the force of more than 220. Why so few?

“I

think the physical demands, being locked away for 24 hours in a sweaty

bunker with a bunch of dudes is probably not very appealing (for

women),” offers the firefighter, who requested anonymity.

Moore

figures it’s a matter of awareness. “The fire service has been slow to

catch up,” she says. “We’d have fire safety weeks in school, and

firefighters would come. They were all men. I just didn’t associate

myself with that, growing up.”

The most qualified

Moore

says she’s never felt uncomfortable in the department due to her

gender. “I’ve always felt OK and accepted,” she says. “That comes from

being OK with who you are.”

Reyne says that gender was the least of his considerations when he promoted Moore.

“We

have a lot of smart people on the department – there were people that,

if she would have said no or when she retires, could take over the

training division,” Reyne says. “At this date, at this time, she was

clearly the most qualified.”

Training, Moore says, is more than just spraying water, practicing rescue techniques and rehearsing first aid.

Firefighters

tend to be self starters, and so Moore says that encouraging healthy

eating habits and otherwise looking beyond what to expect in burning

buildings and accident scenes is an important part of her job.

“Sometimes you need to be told, ‘You need to eat,’” Moore says. “Maybe

you need to think about taking a nap. … We are not here to make robots.

We are making better people.”

People

skills are important, she says, and firefighters feel things, too, as

they see tragedies unfold and lives changed forever. “I am there, and

I’m vulnerable and I feel the hurt and the pain and the unknown,” she

says. “When I first came on, it’s ‘You don’t talk about those things.’

You do need to talk about them.”

During

last month’s promotion ceremony, Moore appeared to tear up a bit as

Patrick Kenny, a friend who is fire chief of Western Springs near

Chicago, pinned on her new badge. Langfelder talked about glass

ceilings. Reyne talked of solving all of the department’s problems

during long-ago talks with Moore across kitchen tables.

At

one point during their careers, Reyne and Moore were both assigned to

Station Two, where the future chief developed an admiration for Moore’s

ability to pilot a fire engine through narrow, dark roads near Lake

Springfield as well as her work ethic. “She always stayed busy,” the

chief recalls. “Always on her computer and always working. She goes 100

mph.”

There will, Moore says, be no surprises with her in charge of training.

“I

think I will be fair, and they will be aware of my expectations,” she

says. “We will prevent harm, and we will be sensitive about what we’re

doing.”

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].