George Sinclair started building skateboard ramps as a bored Petersburg teenager in the 1970s. At 16, the city of Petersburg paid him $300 to build a 10- foot half-pipe for a contest at a citywide event. “I built it, they had the contest, and then they gave the ramp to me,” he said. The young Sinclair’s handiwork became part of a backyard skate park which had evolved from a former basketball court.

Sinclair left Illinois briefly to attend Northland College in Ashland, Wisconsin, where he earned degrees in environmental science, biology and mathematics. When he returned to central Illinois, he was surprised at the changes the early ’80s had wrought in terms of skateboarding opportunities, and not in a good way. “Before I left, we had skate parks and some infrastructure we had built – but when I got back here it was absolutely dead, there was nothing to do.” That changed one day in the early summer of 1985 when Sinclair happened to see a photo in the State Journal-Register of skater extraordinaire and NIL8 bass player Bruce Williams frozen upside down on his backyard ramp under a headline reading “Lord of the Board.” Sinclair tracked Williams down and struck up a lifelong friendship. “Bruce and Gary Brammer and Bill Jackson and I skated together for two years on Bruce’s ramp,” he said.

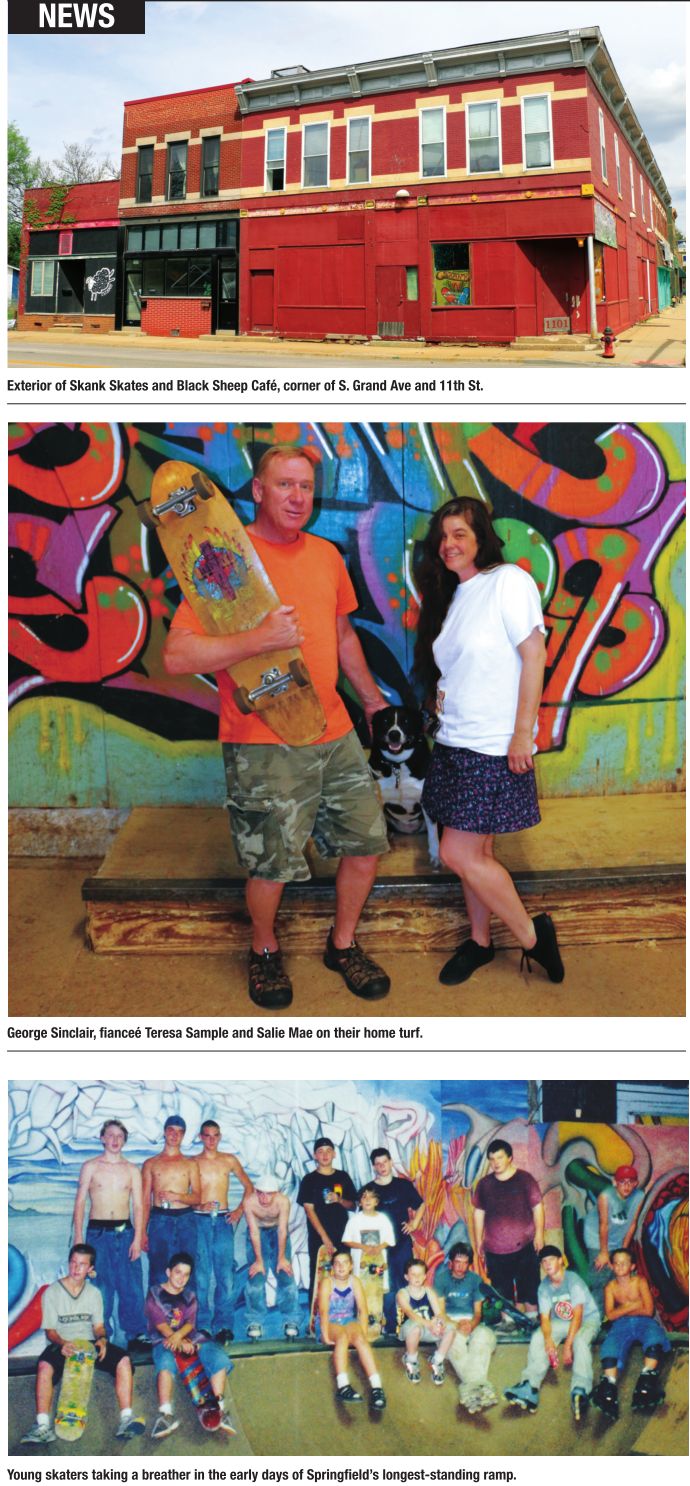

In the winter of 1988, Sinclair – who had gone into business with his father selling commercial and industrial lighting – rented a building at the corner of South Grand Avenue and 11 th Street and Skank Skates was born. Not that it was an easy birth. “We built the ramps and opened on a Saturday in December. Then, that Monday morning, the city came in and immediately shut us down.” Undeterred, and using green shag carpeting from his childhood bedroom for sound insulation -- “We could have a raging session going on the ramp with music blaring and everything else and you could walk right by that window outside and not hear a thing” -- skating continued daily during the duration of this initial closure, with Sinclair never accepting a penny from skaters until he was able to open back up legally. “You’d think it took an act of Congress to get that done, but I finally opened again. After that, it seemed like everything we touched turned to gold for the next couple years.”

In addition to becoming a Mecca for skateboarders, “Skank’s” (as its friends call it) soon became a popular venue for the kinds of speedy, irreverent punk bands favored by skaters, with the aforementioned NIL8 leading the pack. Things did take a dark turn for the venue in 1999. Sinclair had obtained three demolition permits from the city to gut the building’s upstairs floor, which he proceeded to do. “Then the city inspectors showed up with 14 people – man, they even brought the interns – and they put a sticker on my door and told me, ‘You tear this building down or we’re going to.’ There’s nobody to appeal to for a thing like that.”

It took over a month, but the dauntless Sinclair eventually arranged a meeting with then-mayor Karen Hasara, who was impressed with the positive community regard held by Sinclair and Skank’s. She put her assistant, Brian McFadden (currently Sangamon County administrator), in charge of overseeing his projects, which paved the way for development of the various businesses which in 2018 occupy buildings owned by Sinclair on that same corner of South Grand, including music venue Black Sheep Café, which opened in 2005, and the more recent Dumb Records music store, Boof City skate shop and the Southtown Sound recording studio.

For most of the past three decades, Sinclair’s work in commercial lighting underwrote his DIY labors of love, but the company he worked for was recently bought out by a larger corporation, replacing Sinclair with its own reps. “I’ve been trying to get work doing contracting jobs or painting houses – and that will handle the day-to-day expenses, utilities, etc. – but things like property taxes and insurance keep going up to where you can’t seem to ever get the ends to meet.”

Sinclair is currently raising funds by reaching out to people who were skaters or were in punk bands in the ’80s and now are established and would like to see Skank’s and its offshoots continue. “In 30 years, I’ve spent every dime I ever made on this place and that’s what I’m going to continue to do. Every time I call someone about estate planning they won’t talk to me because all I have is equity.”

To help out Skank Skates, visit https://www.gofundme.com/project-southtownspring-fundraiser. All donations benefit Project Southtown, a nonprofit charitable organization.

Scott Faingold can be reached at [email protected].