Rube Goldberg elevates learning for fifth-grade engineers

Everyone wins when Engineer in the Classroom (EITC) arrives in area fifth grades for 12 weeks each winter. Engineers from local firms visit participating classes – this year 12 – to generate excitement about careers in science and math. Classroom teachers engage students of all abilities and learning styles in an unforgettable cross-curricular experience. And students learn physics and math, as well as teamwork, design, problem solving and public speaking. They learn the fun way – by building a crazy contraption out of recycled, repurposed junk. Illinois Times visited two teachers’ classes – Dan Hartman’s class at Dubois Elementary School and Teresa Wolters’ class at Springfield Christian School – from early design through competition at Lincoln Land Community College. This year’s mission was to create a machine with an orbiting object using at least 10 steps, in a space no bigger than 3 feet x 3 feet x 3 feet.

Science and math were never livelier. Add a traveling trophy and bragging rights for the most successful project and you’ve got a winning combination.

While traditional classrooms teach and test, the EITC model is do and discuss. Students engage Newton’s three laws of motion and the six functions of simple machines as they apply the engineering design process to a fanciful Rube Goldberg. Students document their work in a bound journal, then present the whole thing at the regional Rube Goldberg Design Contest funded by private donors, engineering firms and other corporations.

“To be here and going strong for 12 years speaks to the merit of the program, even up against national testing,” says Springfield civil engineer Adam Pallai of Martin Engineering Company, who has worked in the program since it expanded from Decatur to Springfield in 2006 and who serves on the EITC coordinating committee. “Teachers make time for it.”

Among the engineers, teachers and students it was hard to tell who was having the most fun.

Dan Hartman: “It’s everything I want to do.”

This was Dan Hartman’s third year as a teacher participating in Engineer in the Classroom. His class won the regional title two years ago. “For me, it started with, ‘Oh, that sounds like fun,’ but quickly became, ‘This is everything that I wanted to do and be as a teacher, to quit doing the same things over and over again, to make a difference and impact the next generation.’ “With this, we don’t teach separate core subjects. We make connections across the curricula. Engineer in the Classroom demands students all become readers, writers and researchers. They apply mathematical skills to every academic area.”

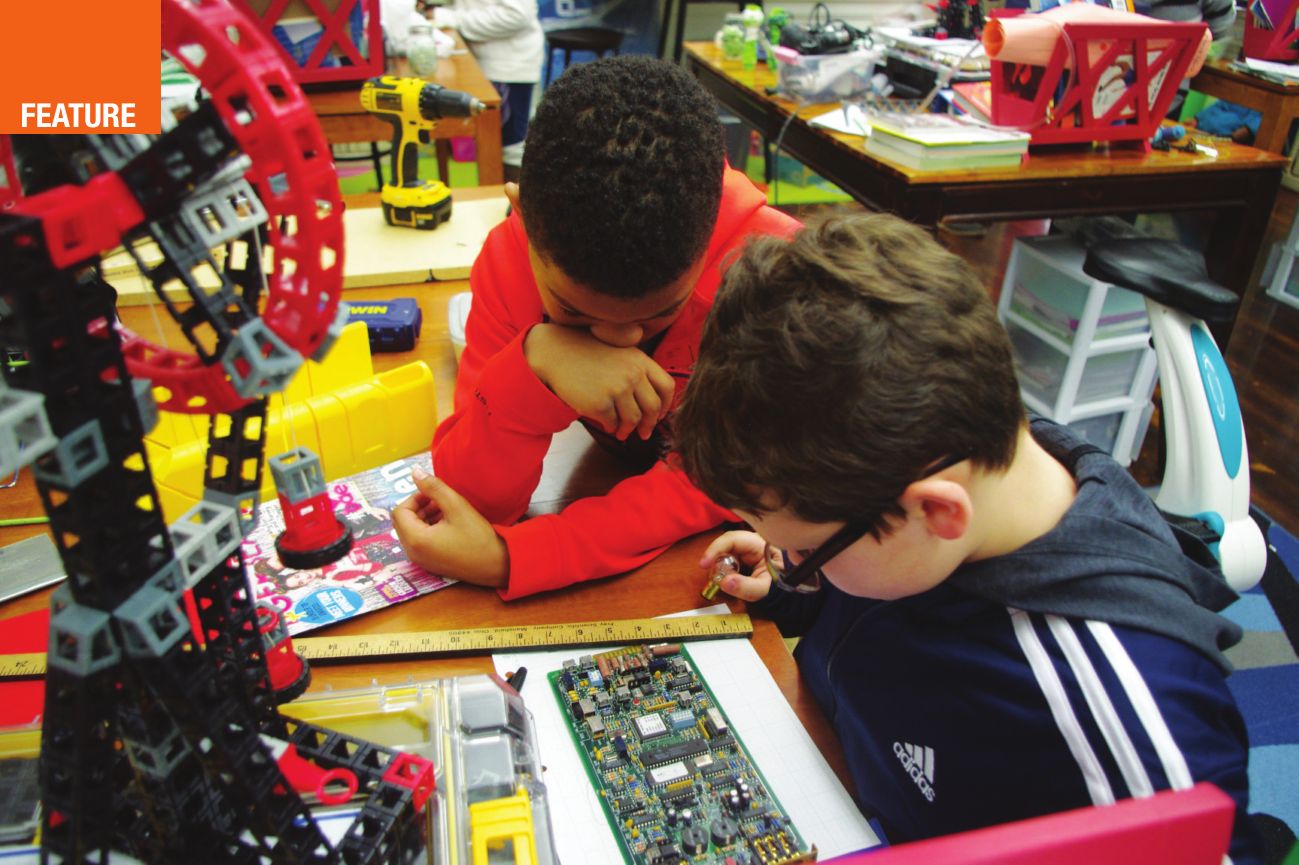

This year, Hartman’s class

built a model of a giant Minecraft Ender Crystal with the help of

engineers Jim Michael and Chris Groth of Crawford, Murphy & Tilly.

“We wanted to make something that’s never been made before,” said

student Makaye C. Engineer Michael describes the moment the kids

suggested the huge, rotating cube as the first of many “yes!” moments to

come. “It’s fun,” says Michael. “It’s tinkering!” Hartman likes the

creativity in motion.

“The

students aren’t sitting in nice even rows all day,” he says. “They work

standing up at tables, getting oxygen to their brains.” On engineer

visit days, the students work in teams. They move around the room

looking for items in bins, experimenting with ideas at the work tables,

talking with each other, and learning to use various tools. It is a

learning lab, not only for scientific principles, but also for the

National Education Association’s “Four C’s” for successful students:

communication, collaboration, critical thinking and creativity.

“This

initiative is everything education ought to be,” Hartman says. “We

start with a project and then figure out why all the concepts and

principles actually matter.” For example, “We used fractions to build a

scale model out of Rokenbok [connecting blocks] and now the kids can see

why fractions matter.”

Project-based

teaching should be the standard, not the exception, said Dr. Brad

Christiansen, who led a teacher workshop at Dubois school in January.

Christiansen works in Illinois State University’s Center for

Mathematics, Science and Technology, which helps teachers integrate

science, technology and math across curricula at all levels. The key is

inquiry-based activities that engage students through an active,

experiential project. “The project provides the context, necessity and

pathway to learning,” says Christiansen.

Hartman

is a believer. “If you do the principles first, students can’t make the

connections to everyday life because you’re out of time. This project

takes knowledge and turns it into wisdom. We’re giving these kids

opportunities that my generation could only dream of.”

“It’s

really fun,” says 10-year-old Porter M., “because you get to DO

something, cut with a saw or use a screw gun. It’s really hands-on. We

all work together.”

And then there’s the built-in competition.

Veteran

program engineers Adam Pallai and Jim Michael enjoy a friendly rivalry

each year. “Anytime you put engineers in a contest together, it’s game

on.”

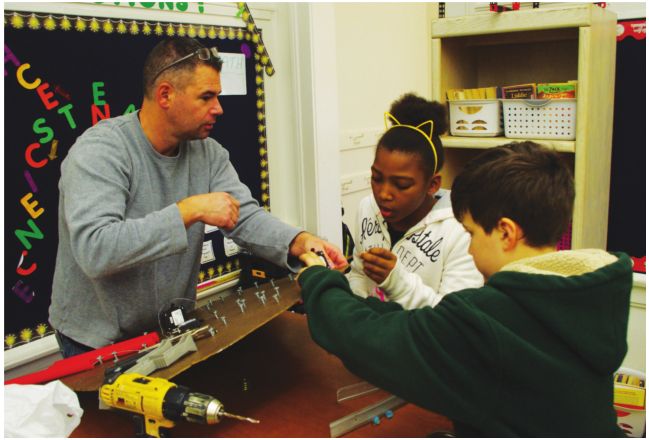

Michael and

Groth, who have worked together in the program for a few years, have

perfected their teaching style. “Every question gets answered with a

question,” Michael says of the team’s seamless method. “There is a lot

of planning, though,” to create those wonderful aha! moments. “Chris and

I meet for 15 to 20 minutes before each class. We discuss what needs to

happen and how to get the kids to figure it out and go in that

direction.”

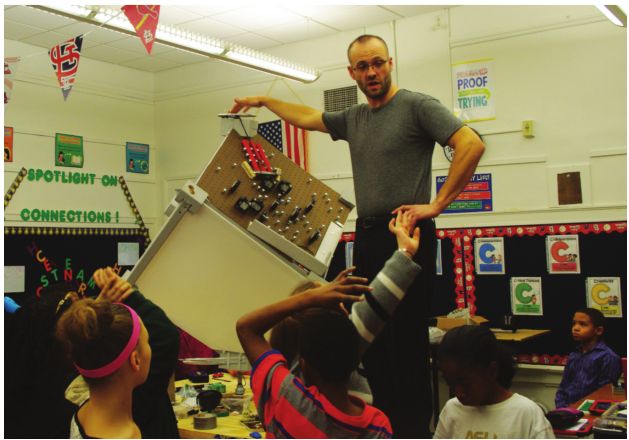

One

Wednesday, Groth met with students to complete a step where marbles had

to roll down a tilted pegboard into a plastic juice bottle. “We need to

figure out how to get more marbles to go into the juice bottle,” Groth

began, identifying the problem with characteristic clarity. “We’ll work

on that this afternoon. Anyone have an idea?” With that, the diagnostics

began, with students recording the results of each trial in the

journal, on the board and on two iPads filming from different vantage

points. “Did that work better or worse?,” Groth asked after each try. “I

need to know the percentage of marbles that make it into the tub ...

Let’s try this again to see what our success rate is ... How about if

someone creates a table for the results? ... OK, we’re ready. Give us a

3-2-1.” Student Andre S. wasn’t worried. “We see the problem and try to

make it better.”

Teresa Wolters: “When do we get to start Rube?”

Teresa

Wolters’ classes at Springfield Christian School have enjoyed a history

of success competing in the Rube contest, so younger siblings come into

class each fall eager to begin. “I participate in the EITC program each

year due to the excitement in learning it produces. One of the first

questions [the students] always ask during the first weeks of fifth

grade is, ‘When do we get to start Rube?’ “The students become invested

in their learning and grow, not only in the areas of math and science,

but also in public speaking, writing, teamwork and confidence.” This

year’s Rube theme was “At the Movies.”

By

our second visit, the student teams had truly become engineers with a

passion to test and perfect their working Rube and deliver a winning

presentation on contest day. They’d written a script, donned costumes

and props, and were running dress rehearsals in front of younger

classes.

Engineers

Adam Pallai and Al-Barrae Shebib worked with the class this year. “What I

like to see is kids getting excited learning engineering concepts,”

says Shebib, a structural engineer with the Illinois Department of

Transportation. These are hands-on experiences they’ll keep for many

years. Whether they become engineers or not, we’re teaching them to be

critical thinkers and problem solvers for the next 5 years, 20 years and

more. Engineers push innovation. This helps equip them for the future

we’ll have together.

“After this experience, they won’t be afraid to take an engineering approach for the rest of their lives. Whatever

their next step in life is, they’re going to be ready for the challenge.

Fearless. They can see the possibilities of what this allows them to

do. That’s going to carry with them forever.”

Pack up the hot glue and gray tape – it’s contest day!

One

of the hallmarks of the EITC program is inclusivity. This isn’t an

afterschool club for kids who have flexible transportation and can pay

dues and fees. With the exception of the regional contest in Lincoln

Land’s Menard Hall, EITC happens during the week, for students of all

socioeconomic levels and genders.

This does mean, however, that some classes put on bigger, brighter shows on contest day.

Some

classes arrive 20 or more strong, wearing new matching slogan tees and

costumes, displaying Rubes made of dozens of colorful cast-off toys.

Others arrive with fewer than 10 earnest students, no matching outfits,

demonstrating sparse Rubes made mostly of nuts, bolts and rebar. “Some

students don’t even get to come on contest day because they don’t have a

ride,” said one of the engineers. But everyone brings their best. The

judges’ ratings for teamwork and the written journal help even the

playing field.

Early

morning Feb. 24, teachers, engineers, students, families and judges

gathered in the lower level of LLCC’s Menard Hall to run the Rubes. Each

class had 10 minutes to move its machine into position and 10 more

minutes to present it and get it to run twice. Judges offered encouragement and

asked thoughtful questions that put students at ease. Parents videotaped

and cheered from the audience. And tense teachers crouched along the

front and sidelines willing their machines to work.

At

3 p.m., EITC coordinating committee member Terry Fountain, a retired

engineer who now serves as a volunteer classroom engineer, quieted the

crowd to begin the awards presentation. All classes received

participation packets. The top five classes with the best teams,

machines and journals received additional resource books and games. And

the top three classes advanced to the state championship in March –

including both Hartman’s and Wolters’ teams.

It was a proud day for the committee.

“We’ve

had about 4,000 fifth graders go through the program in the past 12

years, approximately 300 just this year,” said Fountain. “We’ve had

several students go on to become engineers.”

And

that is one of EITC’s main goals. “Our ultimate goal,” said Pallai, “is

that somebody, even one person, gets a little interested in becoming an

engineer.

“We need

more engineers to carry the torch to plan safe, cost-effective roads,

bridges, software, medical devices and water supply – to see that an

engineer somehow has touched every single thing in their lives and say,

‘This may be something I want to do.’” Amy and Tom Brunner of

Springfield were in the audience supporting their youngest child. “This

is really important. All five of our children have gone through this

program. It opens the door to seeing what they can do for their future,”

said Amy. “Our oldest son, James, is a sophomore now at Missouri

Science and Technology in Rolla majoring in nuclear engineering.”

In

the end, whether the projects ran smoothly or not, everyone had a good

time. A Rube from Fairview Elementary, which sent one of the smallest

teams of the day, ran many times successfully in the classroom but

didn’t complete the task on contest day. “I thought the presentation

went very smooth,” said fifth-grader Preston P. of his team’s effort.

“Everyone was calm, not nervous. I’d probably give us five stars on

that. But I would say we probably ran our machine too much yesterday and

it lost some of the tension. We had to keep recalibrating it today.

“But

I would tell anyone,” Preston continued, ‘If you ever get a chance to

be in the Rube Goldberg contest, never say no. Sign up!’ It’s like going

on your first roller coaster ride at Six Flags, upside down on the

Batman. You get so much joy and fun out of this.”

More is better, spread the word If it’s so great, why doesn’t everyone do it?

The

short answer is, the program needs more engineers to serve more

classes. There’s a waiting list of classes that want to participate.

The

longer answer is, the 13 classroom teachers who participated this year

possess willingness, discipline and trust to engage in project-based

teaching and learning. “This is all a part of my philosophy of educating

and leading children to success for life, not just fifth grade,” says

Hartman. But, he adds, it “hinges on solid classroom behavior and a

management plan where elevating the expectations to very high standards

for all involved is the norm. It’s not easy, nor is it for the faint of

heart.”

Schools at all

levels benefit from teachers and administrations who are willing to set

these expectations, create experiential curricula, marshal needed

outside resources and affirm successes. Dubois Principal Donna Jefferson

supported her three participating classes by attending this year’s Rube

Goldberg Design. “I’m so incredibly proud of these amazing future

engineers. They lived this work every day – the designing, problem

solving, perseverance, dedication, teamwork. All of the components of

science, math and engineering came together in something so powerful

that is their own creation. They will live with this forever.”

To participate in Engineer in the Classroom, email Adam Pallai at [email protected].

For

more information about ISU’s Center for Mathematics, Science and

Technology, including a variety of free resources, visit https://cemast.

illinoisstate.edu/about/ or phone 309-438-3089.

DiAnne Crown is a reading and writing coach, and frequent contributor for Illinois Times. For more information, email info@seasonsofparenting.com.