Ann Ridgeway was on her porch when the crash came.

No one had told neighbors that a massive metal building was going to fall that day in October 2014. Towering more than 10 stories, the so-called dryer building – locals say artificial sweetener was once made there – produced plenty of dust and debris in its death throe.

“It looked like something was on fire,” Ridgeway recalls. Brian Dearco was repairing his roof a couple blocks away from Ridgeway’s home, directly across the street from the mill.

“As soon as the building came down, millions of mosquitoes and gnats came out,” Dearco says. “I broke out in a rash. My wife did, too. … You could smell it in the air after that building came down. It smelled like gas, so the fire department came.”

Responding to reports of a collapsed building, fire engines swarmed. But there was nothing to worry about, an owner of the site assured firefighters – he had a permit to demolish the building, according to fire marshal Chris Richmond. And so the fire engines left, and work resumed, with crews sorting through rubble to recover scrap.

There was, in fact, plenty to worry about. Permit applications filed with the city stated that asbestos inside the building would be cleaned up prior to demolition, but that didn’t happen. No regulator would have allowed the dryer building to be torn down absent pre-demolition cleanup of asbestos, which was used as a building material throughout the plant.

Once common as a building material, asbestos is a carcinogen that can cause chronic and irreversible lung damage. The more exposure, the greater the risk, and it can take years for symptoms to develop. The mill contained a lot of asbestos.

“You just never know,” says Kevin Turner, site cleanup coordinator with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. “One asbestos fiber from 20 years ago could cause some sort of lung issue. Or you could be exposed to it for 10 years and not have any issues.”

A consultant who conducted an environmental assessment of the site in 1991, the same year that Pillsbury sold the mill to Cargill, found pipes and tanks tagged with caution labels warning that asbestos was present. Pillsbury had an ongoing asbestos abatement program based in part on a 1987 survey that included taking as many as 500 samples of material throughout the plant and testing for asbestos. Pillsbury during the late 1980s identified priorities and started cleaning up sections of the plant, according to the 1991 report by the Minnsesota-based consultant.

“The facility has implemented an asbestos awareness training program for its personnel,” the consultant wrote more than a quarter-century ago. “Asbestos removal and disposal is performed by licensed asbestos removal contractors on an as-needed basis.”

Subsequent surveys found plenty of risk.

A 1996 report commissioned by Cargill, one of the planet’s largest food companies that acquired the mill in 1991, identified more than a mile of pipe insulated with potentially deadly asbestos. In 2008, a scrapper in search of electrical equipment hired a consultant who found asbestos in subterranean electrical vaults.

Soon after the dryer building came down in 2014, the city demanded that the mill owners obtain proper permits while also registering buildings on the site as vacant. “That’s kind of where things really kind of started rolling,” says Springfield fire marshal Chris Richmond.

But real heat didn’t arrive until the late summer of 2015, when state regulators got a call from a man who’d been getting paid in cash to cut asbestos insulation from pipes with a linoleum knife, then stuff the carcinogenic waste into plastic garbage bags.

It’s not clear what might

have prompted the apparent falling out between Don Dufer, the man with

the utility knife who blew the whistle, and Joey Chernis IV, the man who

hired him – Duter contacted the state shortly after he was fired,

according to court documents. Regulators say a whole lot of damage was

done before a court injunction stopped work in the fall of 2015.

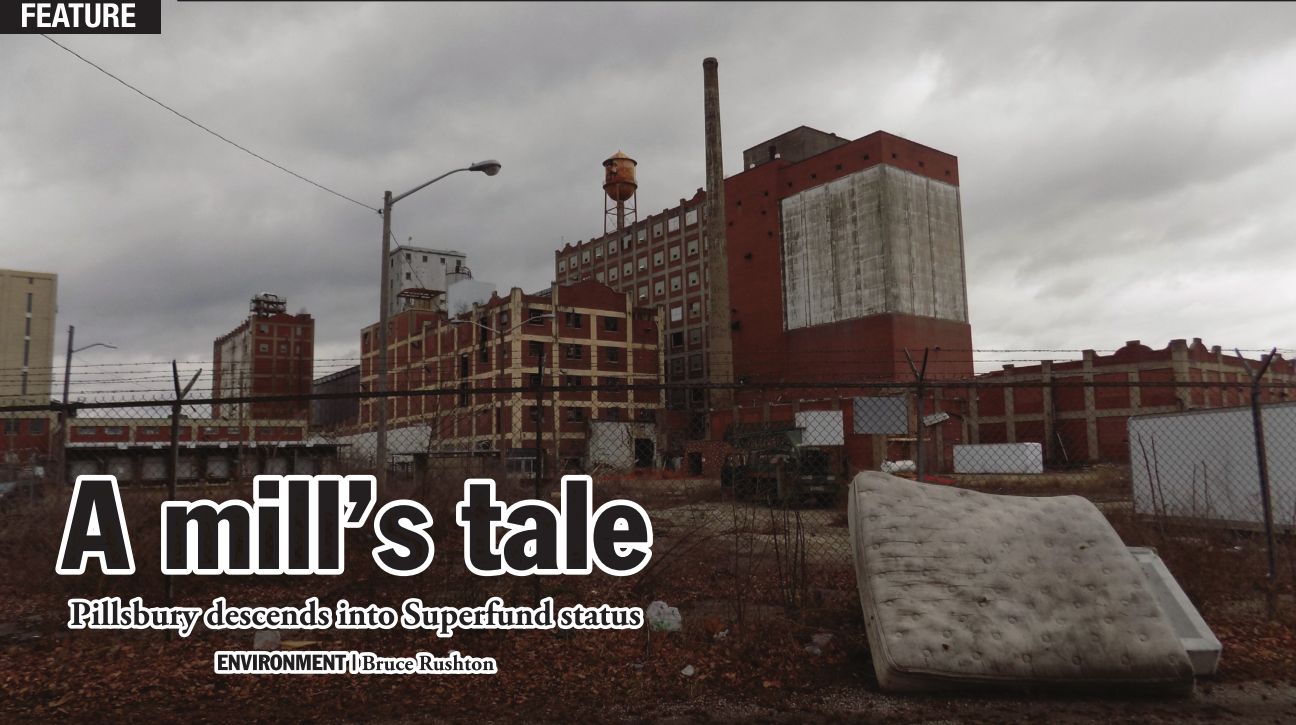

Spreading contamination If Springfield was Gotham and The Joker needed a hideout, he could do a lot worse than Pillsbury Mill.

Although

the dryer building, a boiler room and parts of warehouses have been

demolished, an estimated 850,000 square feet of space remain. Neighbors

say the cops have told them that officers won’t go inside the cyclone

fence that surrounds the property. Springfield police did not respond to

an inquiry, but it isn’t hard to imagine why police officers wouldn’t

venture inside the mill.

For

one thing, it’s dark, with plenty of places for bad guys to hide. For

another, large sections of floor and other structural parts of the

building are missing. There is also pollution.

Left

alone, asbestos isn’t necessarily dangerous stuff. Indeed, the silver

coating on massive grain elevators on the mill’s east side contains

asbestos. Regulators say that the coating is nothing to worry about, at

least not yet. But tearing away insulation and other materials that

contain asbestos can set free carcinogenic fibers that can float in the

air and cause substantial health risks. And that, regulators say, is

exactly what has happened inside Pillsbury Mill.

“(T)he

results of the scrapping and demolition activities have left a large

amount of loose and friable asbestos all through the buildings and

asbestos containing rubble and debris outside of the buildings which is

exposed to the elements,” Turner wrote a year ago in a memo assessing

the situation.

Some of

that loose asbestos was in the dryer building, according to federal

prosecutors. Richmond, the fire marshal, downplays any threat to the

neighborhood, although he acknowledges that witnesses saw a large cloud

of dust rise

when the building fell. “Some of that dust cloud presumably went

throughout the neighborhood,” Richmond says. “All the testing done with

the Illinois EPA and the U.S. EPA – asbestos particulate tests and air

monitoring – has shown very little if any asbestos made it outside the

fenced industrial property. Presumably, the lion’s share, even all of

it, settled within the property.”

Court

documents, however, paint a darker picture. “By improperly handling and

depositing (asbestos), defendants and/or their agents have caused or

allowed uncontrolled discharges of asbestos fibers into the environment,

creating a substantial danger to the environment and the public health

and welfare, endangering the health and well-being of defendant’s

workers, nearby residents of the facility and the general public,”

lawyers with the state attorney general’s office wrote in a 2015 request

for an injunction to halt work. The injunction was granted.

Asbestos from the dryer building and other parts of the Pillsbury Mill likely has spread far and wide.

“All

of that debris that was asbestos contaminated was taken by demolition

recyclers throughout the Midwest in its contaminated form,” Richmond

says.

The plant itself

remains a hazard. Proper asbestos removal requires copious amounts of

water, sprayed just-so while workers remove asbestos-contaminated

material to prevent poisonous fibers from becoming airborne. But no

water was on hand when Dufer used stripped asbestos from more than a

mile of pipe.

Without

water to keep it out of the air, asbestos fibers attached themselves to

dust particles throughout the plant, including particles from the

illegal demolition of the dryer building. “When you’ve got contaminated

dust settling, it contaminates what it settles on,” Richmond explains.

“It settles on horizontal surfaces, and that’s where it remains until it

gets stirred up.”

So

long as the mill is empty, with no dust getting kicked up, there is, at

least in theory, no problem. But the plant hasn’t been empty, despite

no-trespassing signs and a fence topped by razor and barbed wire in

various states of repair.

“Listen,”

Dearco says as he stands outside his house. Sure enough, from a

football field away, the sound of metal-on-metal clanging floats up from

the direction of the mill. Someone, it sounds like, is in there doing

something.

Ridgeway can see the route from her porch. All they have to do, she says, is get a boost up to a concrete ledge that traverses a small building and

leads to the upper portion of the cyclone fence that’s supposed to keep

trespassers out. That the fence is somewhat a joke is driven home by the

presence of a piece of portable scaffolding, apparently scrounged from

within the mill, just inside the main gate. The scaffolding is

positioned such that materials could easily be lifted over the gate and

onto a vehicle parked outside, and mushed-down barbed wire atop the gate

suggests that’s exactly what has happened.

Junkies

and homeless adults ignoring “Danger: Asbestos” signs to steal scrap is

one thing. The nightmare scenario is kids being kids.

“Everybody

wants to do a little Tom Sawyering,” offers John Keller, president of

the Pillsbury Mill Neighborhood Association, the only neighborhood

association with a Superfund namesake.

Regulators

say they’re well aware. “Kids are kids,” Turner says. “I look at it

from when I was a kid. If there was an abandoned building, boom, we were

in it. That is a population that we’d be concerned with.”

“We live in a good town” The mill wasn’t always like this.

When Keller helped launch the neighborhood association in the 1990s, the mill was still open. But just barely.

By

the time Cargill purchased the mill from Pillsbury in 1991, the plant

had trimmed operations, reducing employment to fewer than 350 workers.

At its peak, the plant had employed 1,500 people. It was built on the

eve of the Great Depression, and Pillsbury had to be persuaded of both

an adequate water supply and paved streets, plus railroad access, to the

site before committing to a $1.5 million investment in 1929.

“We live in a good town,” the Illinois State Journal gushed

shortly before the mill opened, noting that 120 building permits had

been issued in September 1929, just one month before the stock market

crashed and sent the entire nation into economic catastrophe. “We know

it, and large industries are realizing the fact more and more.”

Through

the years, the mill manufactured flour as well as a variety of cake and

baking mixes. The neighborhood smelled like Grandma’s kitchen and

boasted grocery stores and butcher shops and taverns and restaurants.

The mill was a beacon.

“At

nighttime, it used to be lit up,” recalls Keller, who no longer lives

in the neighborhood but still spends time there, picking up trash. “You

come in from Riverton, you go over the overpass, the first thing you saw

was the mill sticking up.”

By

the late 1980s, Pillsbury had cut back operations and was looking to

get out. It sold the mill to Cargill in 1991 for $19.2 million, roughly,

in inflation-adjusted dollars, what the plant had cost to build when

Hoover was in the White House. Cargill, the nation’s largest privately

held corporation, closed the mill in 2001. Seven years later, it sold

the mill to Ley Metals Recycling for $257,000, less than a quarter of

what the plant was worth, according to Sangamon County taxing

authorities.

After

filing required paperwork with the Illinois EPA and receiving permits,

Ley removed asbestos from some of the premises to allow salvage

operations, then flipped the plant in 2013 to an Indiana-based salvage

company. Sangamon County property records show no sales price; rather,

the mill changed hands on a contract-for-deed basis, records show.

Neither Jim Ley, owner of Ley Metals, nor owners of the Indiana company

could be reached for comment.

The

Indiana company owned the mill for less than a year before selling it

to PM LLC, an ownership group that includes Chernis, According to court

documents, Joseph Chernis, Chernis’ father, helped oversee salvage

operations at the mill. “Joey Chernis was generally in charge of the

facility and its demolition,” lawyers for the state wrote in a 2015

motion asking that work be stopped. Paperwork in the county recorder’s

office shows that no money changed hands when the Chernises acquired the

property. Once again, the deal was on a contract-for-deed basis,

according to county records, that presumably involved a cut of whatever

monies were realized from scrap operations.

Chernis

and his father have a history with Springfield code enforcers. After

acquiring a long-vacant icehouse near Lincoln’s home on Edwards Street

via foreclosure, the Chernises in 2013 leveled the building, then let

the debris sit for more than a year, prompting court intervention to

force a proper cleanup even as the Chernises prepared to acquire the

Pillsbury plant.

That the mill was approaching a brink wasn’t a secret. In 2006, after public brainstorming sessions

cosponsored by the Illinois EPA, an arm of the Greater Springfield

Chamber of Commerce published a report suggesting what might be done

with the vacant site, which was still owned by Cargill. Among the

suggestions was a tax-increment financing district.

“We’re

committed to pursuing this until we have exhausted all our resources,

or we have some alternatives,” Bradley Warren, director of the chamber

group, told the State Journal-Register in 2006. Two years later, Cargill sold the mill for scrap, with no other plans for the future in sight.

Pillsbury

Mill isn’t alone, and perfect answers are rare. In western New York

state, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency last spring ordered the

Beech-Nut Baby Food Co. to pay cleanup costs at a vacant factory the

company sold in 2013, after determining that asbestos cleanup costs

would total $1.7 million for half of the 27-acre site. The sales price

plummeted from $1 million to $200,000 after cleanup costs became known,

according to media reports. Beechnut refused to obey the EPA cleanup

order, saying that asbestos problems were caused by improper demolition

after the company sold the property to a salvage company that didn’t pay

property taxes. Late last year, Montgomery County, where the factory is

located, agreed to pay to remove asbestos from the site at a cost that

could reach $10 million. The county is hoping that state and federal

grants will kick in.

Cargill

did not respond to an emailed inquiry asking why the company didn’t

remove asbestos before selling the Springfield mill or otherwise ensure

that the plant wouldn’t end up a Superfund site. The cleanup overseen by

the federal EPA in Springfield has cost $1.8 million. Nearly 2,200 tons

of contaminated debris has been removed.

“These

types of facilities that have asbestos are all over the country,” says

Turner, who says he’s overseen at least a dozen government-funded

cleanups of such sites in Illinois since he began work in the Superfund

program in 1989. “There was nothing in Pillsbury that scared me. There

was nothing in Pillsbury that made me nervous or that I had not dealt

with before. The only thing with Pillsbury was its size. It was the

largest cleanup of this nature that I have ever done.”

And

the job isn’t finished. Turner believes demolition is the next logical

step, although he acknowledges that he doesn’t know who would pay or

what it might cost. For now, an injunction barring any scrapping

operations remains in place as part of a lawsuit filed by the state

against Chernis and other mill owners for improper disposal of asbestos.

In addition, Chernis is awaiting sentencing in federal court after

pleading guilty to charges relating to improper cleanup of asbestos and

making false statements in the state court case. Jail time is mandatory

under federal sentencing protocols. Mark Wykoff, Chernis’ attorney,

declined comment.

An

obsolete mill. A massive amount of asbestos. A series of deals conveying

title from one scrap company to the next. And now, a post-apocalyptic

scene ringed by cyclone fence and razor wire in the midst of residential

neighborhood. Was this something that anyone should have seen coming?

Yes, Richmond acknowledges.

“Like a freight train,” he says.