Civil War museum keeps going

It was July 13, 1864, when Wilmer Dickerson of Jacksonville came across a chilling sight while marching through Georgia.

After

nearly three years as a Union soldier, Dickerson had been through

several battles, but the most disturbing thing he’d seen during the

Civil War was a skeleton hanging from a tree, he wrote in a letter to

relatives during the Atlanta Campaign. There was Confederate money in

the dead man’s pockets. Whether he had hanged himself or someone had

done it for him, Dickerson wrote, no one knew.

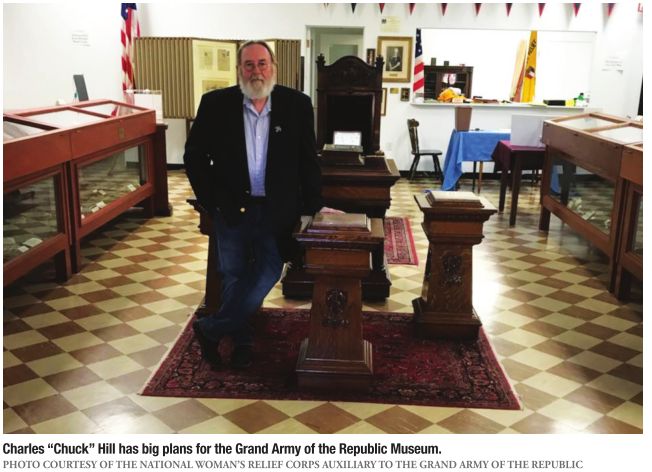

After

reading the passage chosen at random, Charles “Chuck” Hill, new curator

of the Grand Army of the Republic Museum on South Seventh Street,

closes a manila folder stuffed with Dickerson’s letters and smiles

slightly, almost in wonderment.

“I

just happened to pick that out,” says Hill, who only days ago put

Dickerson’s dispatches into chronological order. “There’s no telling

what else is in there.”

Barely

a week into his new job, Hill is making plans for a museum that’s been

closed since August. The National Woman’s Relief Corps, which owns and

operates the museum, hopes to reopen the building in April. And when

doors again open to the public, the museum will, the corps hopes, be a

much different place, one that tells stories and presents artifacts in

scholarly ways as opposed to a warehouse filled with cool things thrown

willynilly into display cases.

Anticipating

a more professional approach, Kathy Bower, secretary for the National

Woman’s Relief Corps, has purchased 10 or so hygrometers to keep tabs on

humidity levels in display cases filled with documents, books, swords,

rifles, medals, buttons and other relics. There is a fresh supply of

white gloves to handle delicate documents and objects. Bower says that

she hopes that the museum can become a place where University of

Illinois students can come for internships.

“In

the past, it’s always been run by a caretaker,” Bower says. “I would

like to see it become exactly what it’s doing now. We’ve got a curator,

and a teaching place. Not to diminish previous caretakers – they’ve been

stellar in what they’ve done – but let’s face it. Every year, we learn

more about proper ways of curation. What we thought was OK to laminate,

we can’t do that anymore, and Scotch tape is not that good.”

A collection worth seeing That the museum, which opened in 1962, contains

fascinating historical objects and documents is undeniable. Just ask

James Cornelius, president of the Elijah Iles House Foundation that

takes care of the nearby Iles House.

“Speaking

as a volunteer at the Iles House across the street, we and everybody

should be pleased that another historic and nationally recognized museum

here in

Springfield can keep going,” says Cornelius, who holds a day job as

curator at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum. “They

have a collection worth seeing.”

The blink-and-you’ll-miss-it building is, perhaps, Springfield’s best-kept historic secret.

“People

do come here to see it,” Cornelius says. “I have, literally, been

stopped at or near that corner by out-of-towners who were looking for

it.”

Cornelius doesn’t

recall exactly when he first stepped into the museum, but he remembers

being impressed. Comparisons to an attic, he says, aren’t quite

accurate.

“Maybe a

little more like a basement,” he suggests. “It was fascinating, but

highly cluttered and dusty. That problem was addressed, though, about a

year ago. It was cleaned up, and the exhibits were much improved.”

For

one thing, Cornelius notes, an American flag that was once proudly

billed as having been on display in Ford’s Theater, complete with a tear

said to have come from John Wilkes Booth’s spur as he fled after

assassinating Abraham Lincoln, is no longer promoted as the absolute

real deal. The proof, Cornelius says charitably, was “not very strong.”

The

first order of business, Hill says, is to inventory the museum’s

belongings and establish provenance. Where did this come from, who gave

it to us, when did we get it and how do we know that it’s real? Already,

Hill has matched a photograph of a Civil War veteran that was in one

display case to a canteen and documents that were in another. As for

Dickerson, Hill hopes to find a photograph of the soldier who saw the

skeleton. Given that Dickerson returned to

Illinois after the war, became a constable and lived until 1926 – the

new curator has already figured this much out – there must be a picture

of him somewhere, which would help bring his letters to life.

“The thing about places like this is, they tell real people’s stories,” Hill says.

Display

cases stuffed with stuff need to be de-cluttered and re-organized. In

fact, new display cases to make objects more visible would be nice.

Storage space is at a premium. Hill is buying surplus filing cabinets

from the state of Illinois. Nineteenth century documents put in plastic

sleeves that appear to have come from Staples or Walgreens need to be

put in acid-free archival sleeves. Artifacts must be researched and put

into proper context.

“What

appears to have taken place in the past was, they put an item in (a

display case) because it looked good, or it was interesting, and it is

interesting,” Hill says. “But what is it?” There’s also the matter of

coherently accomplishing the museum’s threefold mission: Telling the

stories of the Civil War, of the Grand Army of the Republic, a defunct

organization of Civil War veterans who have long since passed on, and of

the National Woman’s Relief Corps, the Grand Army’s auxiliary that has

morphed into a group that lays wreaths on veteran’s graves, promotes

patriotism, sends care packages to soldiers and provides holiday baskets

and other goods to residents of veterans’ hospitals. While the museum

is in Springfield, the relief corps is headquartered in New Hampshire,

with officers and members scattered among several states.

It

seems a daunting task, and Hill, who has spent a quarter-century

working at museums, universities and historical societies around the

country, has no illusions.

As with any museum, Hill says, the task of figuring out history and

organizing collections never ends. He recalls organizing and cataloguing

900 documents authored by Thomas Jefferson while working as an

archivist at the Missouri Historical Society in St. Louis. The

historical society obtained the papers in the 1920s, Hill says. More

than 60 years passed before the documents were properly catalogued.

In

Springfield, the Grand Army’s collection is large and the budget small.

According to its most recent filings with the Internal Revenue Service,

the National Woman’s Relief Corps had $32,342 in revenue in its most

recent fiscal year that ended on Aug. 31, 2016, and expenses of slightly

more than $32,000. The organization ended the year with $88,000 in the

bank.

An itinerant archivist Hill receives no pay, but he gets to live rent-free

in an apartment attached to the museum.

A

Lanphier High School graduate who obtained bachelor’s and master’s

degrees in the 1980’s from Sangamon State University (which in 1995

became University of Illinois Springfield), Hill has hopscotched the

nation during his career. He has worked as an archivist at Eastern

Kentucky University and the Missouri Historical Society, where he had

custody of five journals from the Lewis and Clark Expedition but got his

biggest thrill when he held a note written by pencil by Ulysses S.

Grant: “We’ve taken the second water battery, you can take your ships up

now.” It was sent to a fleet admiral as the siege of Vicksburg, a

turning point in the Civil War, neared an end.

“The first time I picked that document up, I got goose bumps,” Hill says. “It was very moving, and very profound.”

Hill

also has worked as an archivist at the Lakota Archives and Historical

Research Center in South Dakota, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in

Kansas City and the People-To-People Health Foundation in Virginia.

There was also a stint as curator of photographs at the San Diego

Historical Society.

“I usually describe myself as an itinerant archivist,” Hill quips.

After

retiring six years ago, Hill spent four years traveling the nation in

an RV. Eventually, he ended up parked at a friend’s house in Petersburg,

but the RV was destroyed by fire, leaving him in search of a place to

live. He was living at the Inn at 835 when he heard that the Grand Army

museum needed a curator. He has a son in Carlinville and other relatives

within driving distance, plus a heart condition that’s being treated by

doctors in Springfield. In short, everything fit.

“For the next few years, it will probably be good to settle down somewhere,” he says.

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].