HISTORY | Scott Faingold

“You, as individuals, are

very significant to the success of a project like this,” said Floyd

Mansberger of Fever River Research, addressing a group at Union Baptist

Church Sept. 18. The project being discussed was an architectural survey

to create a record of the African-American experience in the

Springfield area beginning with the city’s initial settlement.

Mansberger explained to the assembled group that the personal knowledge

of community members would help identify significant people, places and

events worthy of inclusion in the study.

Mansberger

and Fever River, working in partnership with the Springfield and

Central Illinois African-American History Museum, have been tasked by

the city to take a close look at a large area on the greater east side

of Springfield ranging from Clear Lake Avenue to South Grand and from

Tenth Street to Wirth Avenue. Although they have conducted a wide range

of cultural resource management, architectural history and historical

archaeology projects for the city since opening their offices in 1985 –

including surveys of the west side capital area, Enos Park and

Aristocracy Hill – the current project, encompassing approximately 43

acres and containing 1,369 buildings, is their largest yet, according to

Mansberger.

Due to

the daunting size of the area, Mansberger said that the project will be

in the form of what he called a “windshield survey.” “We’re not going to

inventory every building out there, we’re going to do a drive-through

looking for the more significant buildings, the buildings that we feel

have both historical significance and architectural integrity.”

According to Mansberger,

the National Park Service and the National Register system recognize

significance of historic properties based on four different criteria:

social history (events that contribute to our collective past); notable

people; the architecture itself (specific architectural style or type of

construction method) and archaeology. “Even if there’s a building that

doesn’t just stand up and say, ‘Hey, I’m significant!’ there is often

material under the ground that can contribute to our understanding of

that event or that person or place,” Mansberger explained.

The

process involves finding a building associated with a particular event

or person. There is a wide range of historical resources which come into

play, including atlases, public records, contemporary newspapers,

published histories, historic photograph collections, building surveys

of the landscapes and oral histories. Mansberger said that federal

census records can be extremely helpful, as can city directories. “The

Springfield city directory from 1876 has a seven-page inventory of the

African-American community in the city,” he said. “Another one wasn’t

published until 1926, but it went into great detail over the length of

50 or 60 pages.”

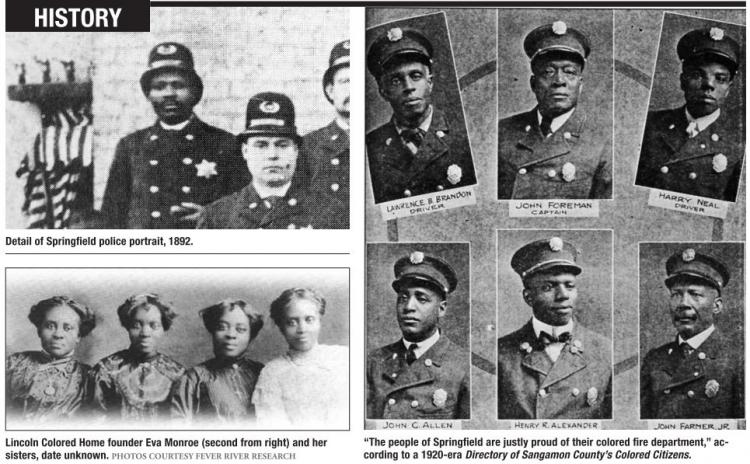

Some of the treasures that have come to light so far include the Negro Motorist Tourist Book which

was published between1936 and 1964 and provided vital safety and

lodging information for black families traveling across the United

States during the era of Jim Crow, including a recommendation for

Springfield’s Dudley Hotel. “Some of these places that are still

standing may not look like much but they may have

integrity or significance to our collective history,” said Mansberger,

mentioning establishments like the Boston Richie moving company and the

Lincoln Colored Home, established by Eva Carroll Monroe, who also

established the Springfield Colored Women’s Club. During the

presentation, several of the community members at the meeting provided

insight and context for some of the slides Mansberger projected. One

woman even pointed out her aunt in a group photo of several youths taken

in the 1920s.

The

National Register of Historic Places, a federal program, along with the

National Parks Service and the former Historic Preservation Agency (now

part of the state Department of Natural Resources) are all providing

support for the project, which has long-term ambitions beyond the east

side of town. (The city is providing $9,240 worth of funding in addition

to a $20,560 heritage grant from IDNR.) “We’re going to look at

African-American settlement in all of Springfield, develop that history

and context and specifically look at buildings in particular

neighborhoods,” said Mansberger. “That way, it can be built upon over

the years so the project can include buildings in other parts of the

city.”

If you would

like to share information with the project regarding events, people and

places significant to the African-American community in Springfield,

Floyd Mansberger can be reached via email at [email protected] or by telephone at 217-341-8138.

Contact Scott Faingold at [email protected].