Once upon a time, before

hip-hop, rap, hot country and even rock in all its formats, jazz ruled

as the cool and popular music of the day. Considered a justifiably

fitting style for an expanding and thriving nation in the 1920s, the era

even acquired the nickname of “The Jazz Age.” In the years following

the slow and serious time of the Great Depression and World War II,

various forms of jazz again dominated the common fancy, until rock ’n’

roll, a sibling of jazz as the other child of the blues, usurped the

crown of popular music for good.

During

this new birth of jazz, from the 1950s and into the mid-1960s, big band

and bebop, swinging singers and cool cats came to Springfield and

central Illinois. The Lake Club (now buried forever, ghosts and all,

somewhere beneath the new Stanford Avenue extension near Fox Bridge

Road) was a national landmark for vocal and jazz groups. The Glade Room

in the old St. Nicholas Hotel hosted many top names in the jazz world,

with late-night jams becoming the basis of local legendary tales.

Later on, other venues,

like Norb Andy’s on Capitol Street across from the Leland Hotel and the

Tack Room in Decatur, became well known for local, live, jazz

experiences.

Springfield

can even lay claim as the birthplace of a few jazz greats. Barrett

Deems, “the world’s fastest drummer” and longtime performer in Louis

Armstrong’s band, was born in town (1914) and spent most of his life

either in Chicago or Springfield. The cool, sultry singer, Shirley

Luster, better known worldwide by her stage name of June Christy from

her work with the Stan Kenton Orchestra and many other groups, was born

in Springfield (1925), and began her singing career as a young girl in

Decatur. Ten-time Grammy award winner Bobby McFerrin, who met his wife

here in Springfield circa 1975 and attended Sangamon State University

(now University of Illinois Springfield) before he had the huge hit,

“Don’t Worry, Be Happy,” got his start as a jazz vocalist and is still

identified stylistically as a jazz performer.

Pause for rebooting But those heady days when jazz was a big thing are

faded memories, as venues and musicians around the country struggle to

keep the music a viable genre as audiences age and interest from a

younger generation is lacking. An example comes from a local jazz

festival that began some 40 years ago with enthusiasm and excitement,

formed from a committed group enthralled with jazz and swing music.

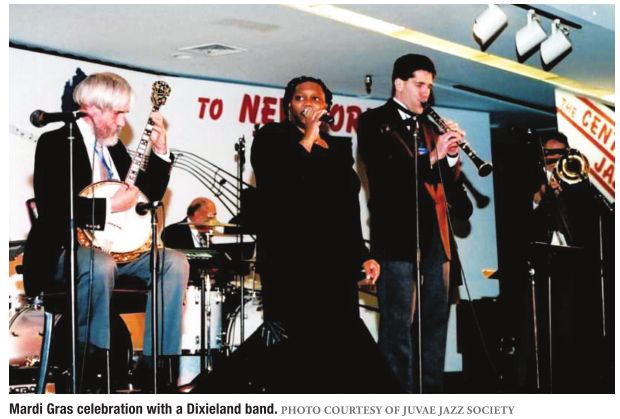

Since the first Central Illinois Jazz Festival was held in the winter of

1976, the CIJF continued at the same venue (originally the Holiday Inn

on Route 36 near Decatur and now the Decatur Conference Center Hotel),

for 42 straight years, including February this year.

Now,

due to circumstances including diminishing audience turnouts, increased

production costs and changes in social media communication, the

Decatur-based host organization, Juvae Jazz Society, put the show on

hold for 2018. The society draws membership from all over central

Illinois, including several members

from Springfield, and plans to regroup while reconfiguring how to make

the long-running event a continuing success. The Juvae (pronounced

joo-vay) will continue to present concerts throughout 2018 during the

rebooting process, then be up and running in 2019 as the full-fledged,

rejuvenated Juvae Jazz Society and Central Illinois Jazz Festival.

The

CIJF ran into trouble before and survived, so board members are

particularly positive about the outcome of this pause in the jazz cause.

After the festival was over in 2000, the hotel changed ownership and

new management decided to no longer sponsor the event, meaning the

society needed to raise $50,000 to make the festival happen. Dedicated

society board members named Margaret “Maggie” Parker-Brown director and

applied sweeping changes to the fest, including locating sponsors and

solidifying the financial aspects of the group. Together the board and

Parker- Brown generated the funds necessary to keep the CIJF going. Maggie came

to the jazz world by hosting bands with her late husband, Jim Parker,

who owned the Tack Room, a tavern in Decatur that occasionally featured

jazz groups. When the couple relocated to Illiopolis and booked even

more bands at a new venue, she learned the ropes of working with

musicians and agents by going to music festivals, jazz cruises and other

venues to check out live groups. Maggie used her expertise as a band

booker and venue operator to keep the fest functioning from the new

beginning in 2001 until 2017, but the latest trials and tribulations

have brought problems more difficult to manage.

Ken

Cole, a longtime Juvae member, explained that those attending the

festival now are many of the same folks who have been coming for

decades, placing the audience into their 70s and 80s. Though a faithful

and appreciative crowd, it’s not one that can continue fully supporting a

three-day festival with several groups and stages. Maggie, now in her

80s, still books all the performers, arranges all the travel and does

many things for the festival that no one else does and no one knows

about. Her style is, as Cole says, “just how Maggie does it.” The

current board is considering several options to improve and invigorate

the festival and even discussed moving the whole event to Springfield,

but decided against it.

Cole

recently attended the Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Jazz Festival, held in

Davenport, Iowa, since 1971, to see what others are doing to keep jazz

events moving forward. It helps that Bix (1903-1931) was one of the most

famous of the traditional cats from the early age of jazz and Davenport

was his hometown. But the organization there has also struggled to keep

its festival alive. Still, the four-day show does bring attendees and

bands from all over the world to one of the largest jazz festivals in

the U.S., proving these things can exist and thrive even now.

As

he talked about the future of jazz as a viable entity and how that

relates to the CIJF, Cole wondered about the lack of music venues and

interest in the more rural areas of the country where jazz is

not what everybody wants to hear. Is there anything that an organization

or festival board could do to reverse these national trends of many

decades? What is the real problem with preserving and presenting jazz as

a current attraction to the general public?

Local

musician Frank Trompeter, a veteran of over 25 years of performing jazz

music in various forms and bands, weighed in on the preservation and

presentation conundrum with a theory on the declining appreciation for

jazz, one he dubbed the “Music of My Teens” theory. Frank says that each

generation gets attached to the music of their “teenybopper” years and

that remains their favorite music for a lifetime. His idea explains why

most attendees at the CIJF, and many jazz and big band fans, are well

over 70 and why rationally each generation has its own music, be it

classic rock, classical, disco, rap or punk. Also Trompeter believes

that jazz, because of its innately, improvisational nature, is

essentially an ever-changing genre, and one needs that change in order to thrive and exist.

“Jazz

is a constantly dying art form in need of innovative techniques to grow

audiences. This can be done in the schools (as blues organizations do),

to aggressively spread music appreciation,” said Trompeter. “Otherwise,

you can end up with a declining group of people and their beloved

personal favorite style of jazz, not recognizing the fact that jazz is

actually also a living art form, with many eras and subgenres. It is a

genre that needs to be nurtured.”

In

discussing the decline of jazz’s popularity, some question why blues,

bluegrass and folk, similiar small-market genres in America, are

generally thriving, while jazz has faded from the public perception as a

popular idiom of music. No one seems to have a definitive answer, but

sales figures prove jazz is behind these other styles in the American

music market.

David La Rosa, writing for JazzLine News reported in March of 2015 that “according to Nielsen’s 2014

Year-End Report, jazz is continuing to fall out of favor with American

listeners and has tied with classical music as the least-consumed music

in the U.S., after children’s music, at around 2 to 3 percent of all

music purchased.” La Rosa continues by explaining the numbers are even

worse when figuring in online streaming and downloading, currently, by

far the most popular form of music purchases.

On

the bright side of the jazz world, most area high schools still have

jazz/pep bands, and as long as the directors are into it and students

are interested, the music continues. Jane Hartman Irwin, professor of

music at Lincoln Land Community College and a longtime performer of

traditional jazz songs on piano and voice, continues to present a local

professional and academic face to jazz. She has won multiple awards for

her performance playing and her academic work, teaching music theory

while directing the ever-popular, LLCC Jazz band, and performing with

her trio and other jazz-based groups in Springfield.

“Jazz

is so rich in emotion and rich in musicality and such a beautiful art

form that transcends so much of who we are,” Jane said. “Jazz does take a

good deal of study and ability to play well and I do hope it becomes

more appealing to new generations. There’s such joy in the music and

seeing students ‘get it’ is an amazing thing.”

The

genre seems to be present, alive and well in area cities. Peoria is

host to the Central Illinois Jazz Society, featuring a yearly program of

local jazz performances, while Decatur is renowned for the academic

jazz program at Millikin University. This past July, Normal hosted the

Third Annual Craft Beer and Jazz Street Fair, pairing over 45 craft

beers with jazz bands outdoors in Uptown.

In

Springfield, jazz aficionados still pine for the Washington Street Jazz

Festival, hosted by the now-defunct Jazz Society of Greater Springfield

in conjunction with the Springfield Area Arts Council from the mid-90s

until 2010. The JSGS later became the Springfield Jazz Society, but the

last online notice about them is in an Illinois Times article

from Aug. 25, 2011. A few local clubs, such as Lime Street Cafe, 411

Bar and Grill and Robbie’s, regularly support jazz, along with a few

rogue bars who occasionally book a band, but the heyday of several

venues hosting raucous and rowdy jazz bands on a regular basis is long

gone.

Everybody needs a chance

New Orleans native and a decades-long

Springfield resident and working musician Frank Parker learned jazz

trumpet as a child in the Crescent City playing with family and friends.

He’s still a regular performer with some NOLA heavyweight artists and

more than a few Springfield folks tell tales of noticing Frank on stage

at Jazz Fest or playing in a prestigious New Orleans bar. Part of

Parker’s local music commitment, mostly done in area bars while playing

with the Debbie Ross Band, leading his own combo or sitting in with

other bands, is giving back to the younger musicians, just starting to

play out. By hosting his Jambalaya Jam during the last couple decades at

various clubs around town (currently he’s doing second Wednesdays at

411 Bar & Grill) he feels keeping jazz alive comes through giving

musicians a chance to play.

“Different

cats come to sit in and I don’t care how good they are, I say, ‘Look,

bro… everybody needs a chance to play.’ That’s how you learn,” said

Parker. “We have more musicians coming to play, like brothers Tucker and

A.J. Good, than we have an audience sometimes, but that’s cool, that’s

cool.”

Parker, who has been in

this long enough to see firsthand the decline of the genre, is also from

New Orleans, where jazz was born, and continues to grow and be a major

music force in the city. He cites the aging population of fans as part

of the popularity problem and also decries the lack of radio programs in

town for not helping to build new, younger audiences. Except for Bill

“Dr. Swing” Hickerson (Sunday mornings) and Larry Corley (Thursday

afternoons) on WQNA, the choices are practically nil for jazz radio

programming without going satellite or online. He believes that most

people don’t really know what “jazz” is, where it comes from, or what it

takes to learn to play and appreciate the music. His answer is to just

keep on, and especially to play well enough that people will like it, no

matter what kind of music they think it is.

As

members of the Juvae Jazz Society continue their commitment to what

famed filmmaker Ken Burns called, “our (America’s) great contribution to

the arts,” they will need to recognize the task ahead, as well as the

legacy behind. The original Central Illinois Jazz Festival began in 1976

simply through the desire of local enthusiasts to share their joy of

jazz with others willing to shell out a few bucks to enjoy a toetapping,

ear-tingling good time. For nearly 20 years, the festival used the

original formula of a four-band lineup, with a few extra all-star groups

and college bands rolling in on Sundays.

Then,

in 1994, after organizers wanted to offer more music, they decided a

jazz club would complement the event and placed a legal pad in the hotel

lobby during the next festival as a signup sheet. After enough

participants joined, they named their new jazz society after Juvae

Marlatt, a young woman from Forsyth killed in a car accident on the way

to a jazz concert in St. Louis near the time the group formed. Soon the

fledgling organization held a meeting, appointed Bob Fallstrom as

president (he was honored in memoriam in 2015 for years of dedication to

the festival and society), and Mike Osborne, who collected dues and

wrote bylaws, as “ticket taker.” In August 1994 they publicly presented

the Barrett Deems Big Band in concert and were officially underway as a

jazz society.

Now,

as the festival faces a hiatus for the first time in 42 years, there’s

time for reflection and rejuvenation. Director Maggie Brown talked of

the necessity of finding “new recruits” because of the age factor of

typical members, of continuing to bring in different types of more

diverse, jazz-related music, from Zydeco to Ragtime, Dixieland to

traditional jazz – all while expanding the festival’s social media

reach. “We just couldn’t do that and continue to organize for the

festival,” she explained about the need to for a break in 2018. “But

we’ll be back with diversified music, always something upbeat you can

dance to. We are all about sharing the happy music.”

Tom

Irwin is a Springfield-based, singersongwriter, folk musician who

wouldn’t know a minor flatted fifth if he played one, but enjoys the

grand sounds of jazz and its many relatives, while sincerely hoping the

genre grows to rise again to great heights of popularity and influence.

Reach him at [email protected]