Illinois Innocence Project wants to help ease exonerees back into society

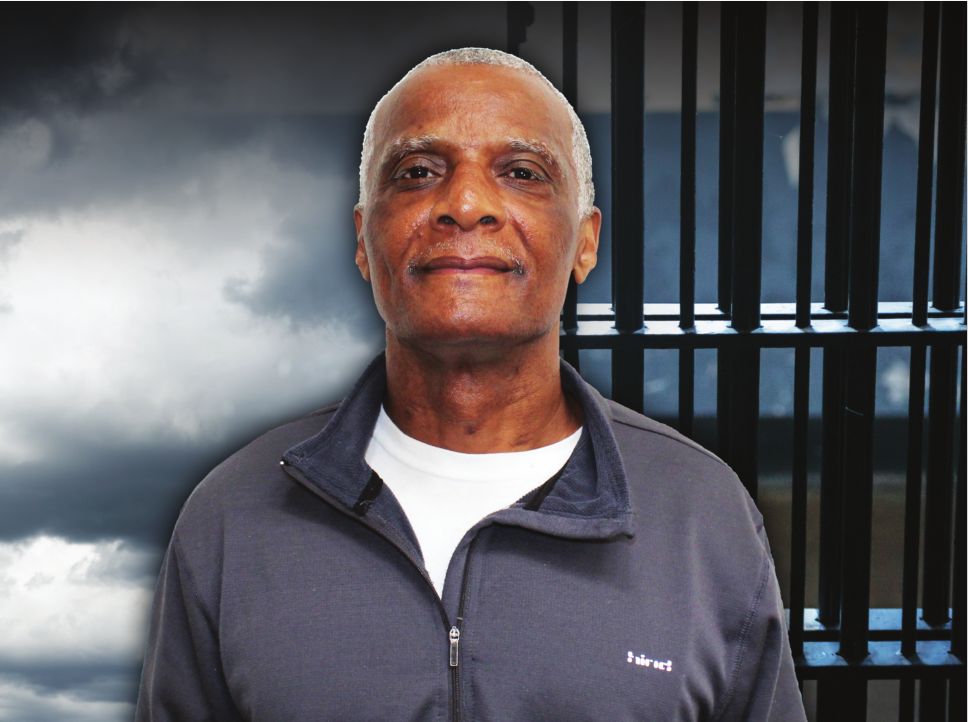

The Illinois Innocence Project based at University of Illinois Springfield, is part of a nationwide network of groups working toward overturning wrongful convictions. Since it began in 2001, the IIP has helped win freedom for 10 innocent people, the most recent of which was Charles Palmer, set free on the day before Thanksgiving 2016, after 18 years in prison for a crime he didn’t commit.

“Initially, the innocence movement was primarily legal in its operations,” said Larry Golden, founding director of IIP. “The goal was to get innocent people like Charles out of prison. Now that we’ve been successful, we’re beginning to face the problem of how to make sure there is the help and support they need when they get out.”

Golden pointed out that the general subject of prisoners reentering society is hardly unique – for example, Gov. Bruce Rauner has stated a goal of having 25 percent of the prison population released within the next 10 years. However, not all released prisoners are created equal. “The state is dealing with this from the perspective of people who have limited terms in prison, so they have a chance to prepare people before they get out.” In contrast, for instance, Charles Palmer had a two-week window during which his being released became a vague possibility and it wasn’t until the day before Palmer’s release that John Hanlon, IIP executive and legal director, was informed it was probable Palmer would be released. “The challenge is almost minute by minute,” said Golden. “The average exoneree doesn’t have any money, a job or even any place to go. It’s a tremendous challenge.”

The challenges for recently released former prisoners extend to all aspects of life, Golden pointed out. “How does this person get a dollar to even buy a soda at the corner store? At the same time, while he is technically an innocent person, when he applies for a job he’s still got this conviction on his record.” To address these problems, the IIP has a small group of graduate students in the social work program at UIS researching the relevant issues and working on practical solutions, including a guidebook listing various helpful resources. “This way in the future, as people get out, they’ll have

something to refer to,” said Golden, who pointed out that nearly all

people released from prison have some form of psychological stress,

post-traumatic stress disorder being particularly common. Other IIP

clients faced serious health issues which have not been treated. “Even

simple things like getting a credit card or a driver’s license or a

library card can prove to be huge challenges,” he said. “Not to mention

all the advances in technology.”

This Saturday, April 29,

Charles Palmer will be among the speakers at the Illinois Innocence

Project’s 10th Annual Defenders of the Innocent event at the Crowne

Plaza Hotel in Springfi eld. Visit http://www.uis.edu/ illinoisinnocenceproject/ for additional details, including costs of reserved seats and sponsorship opportunities.

In many ways, the recently

released Charles Palmer might seem more fortunate than many other IIP

exonerees, due to good health and a fair amount of family support, but

his case still illustrates the uncertainty experienced by many in his

situation. The complications began before he ever set foot outside of

jail.

“I only found

out I was going to be released at about 8:30, 9 o’clock the same morning

I got out,” Palmer remembered. “Mr. Hanlon said don’t tell nobody, so I

had to hold it inside.”

“In

a situation like that, we don’t want the word getting around in the

jail that he might be getting out because there’s all kinds of

shenanigans that occur,” added Golden.

“Even after he told me that [I was being released], it’s never real until it happens,” said Palmer.

Aspects

of the transition process that seem benign, even unabashedly positive,

from the outside can be problematic for the newly exonerated. For

instance, Palmer’s release on the day before Thanksgiving was itself a

double-edged sword.

“Within

24 hours he’s in a celebration with all of his family, many of whom he

hasn’t seen for years, some grandkids not even born at the time he was

incarcerated,” said Golden, “and he doesn’t have any time to even sit

back and say, ‘I’ve been in prison for 18 years, I just got out and now

I’m expected to be a husband and a father and a grandfather, an elder in

the family – as if nothing ever happened with my life.”

“It was even more than that,” said Palmer.

“A

lot of people act like life should just go on. They don’t understand

that you’ve been in a different environment, totally, for almost 20

years. Man, you can’t just come right back out here and jump into

society. It was a ton of people at Thanksgiving

dinner. I smiled, ate, you know, did my best to interact – but that was

trying, being in that family setting. There were a lot of people I

hadn’t seen for years, and I’m already a little bit leery, cautious. I

always think everybody’s got an ulterior motive. These are the struggles

I have now.”

Another

double-edged sword for Palmer presented itself in one of his first

major decisions: where to live. Unlike many exonerees, he has a fairly

robust support system, including his wife, Deborah, who stuck with him

throughout his incarceration. Deborah had been residing in Bloomington,

while most of Palmer’s family was in Decatur, where he had been living

at the time of his arrest. Palmer says he now regrets his decision to

settle in Decatur once released. “His family is in Decatur and so it

made sense when Charles decided that was where he needed to be,” said

Golden. “He gets to spend time with his grandkids there and things like

that, but one of his problems with being in Decatur include avoiding

potentially hostile law enforcement, prosecutors and others who may

remember him from before. You have to remember that outside of his

family, the people that he knows in Decatur are people from 18 years

ago that he may not want to see. We find that to be one of the biggest

challenges for the exonerees – if they go back into the communities from

which they came, it’s more difficult than if they can start a life

somewhere else.”

Trust

and boundary issues often become prominent for those starting anew

after years inside the prison system, and both have been issues for

Palmer in the months since he was set free. He described interactions

with family members who he felt both violated confidences and

over-monitored his behavior. “There’s caring and then there’s policing,”

Palmer explained. “I would go out somewhere and my sister would ask who

I was with, who that person was related to, what’s his last name.

That’s too much. I ain’t gonna go through all that. I try to work things

out in my own way and a lot of times it might be the wrong way. I might

bump my head a couple times but as long as I don’t bump it into the

justice system, I’m great, you know?” At the time he was interviewed,

Palmer was upbeat and energetic, partially because he had found

temporary employment over the past several weeks, doing maintenance work

on a house owned by a member of the Macon County Criminal Justice

Group, an advocacy organization in the area. “If you had asked him how

things were going just two months back, it would have been totally

different,” says Golden. “There was a period of real struggle because he

didn’t have any work and he couldn’t find a job and his days were

structured very differently at that point than they are now. In a lot of

ways, you’re actually seeing him at sort of a good time, in the sense

that he has work to go to during the day.”

Part

of Illinois’ compensation procedure for those released from prison

after being proven innocent is the issuing of a “certificate of

innocence” by the Court of Claims. Once the certificate is received,

compensation is based on the length of incarceration, and for 18 years

in prison Palmer would be entitled to around $220,000 from the state.

According to Golden, there are currently 18 individuals in Illinois due

compensation dating back as far as two years and who have not received

money due them as a result of mistakes by the government. The Illinois

Innocence Project is sponsoring a bill – SB1993 – which would authorize

this money being awarded immediately. However, predictably, the bill has

been caught up in the state’s budget problems.

Some

exonerees are also legally eligible to sue the state for damages in

cases where a violation of the individual’s constitutional rights has

occurred. Such cases can involve lengthy litigation but have resulted in

major awards totaling millions of dollars.

According

to Golden, there appears to be no systematic “program” currently in

place to resolve the challenges individuals face upon release throughout

the network of Innocence Project organizations. The IIP has two social

work students working on a “guide” for their exonerees.

Bryanna

Shinall is a graduate student in social work at University of Illinois

Springfield and works as a research intern for IIP. She and her

colleagus have been tasked with creating systems and procedures to help

exonerees find resources to make the transitions which have proven so

challenging for Palmer and others. “The handbook we are working on takes

a sort of shotgun approach,” she explains, “a listing of all the

services that they might use.” Shinall said that ideally it would be

possible interview future exonerees while they are still incarcerated in

order to perform a personalized needs assessment to determine things

like whether they want to return to their home community or try living

somewhere else and what kinds of services they will require. “That way

we would have at least a little bit of heads-up. But instead we have to

scramble at the last minute because we can’t anticipate when they will

get let out,” she said.

One

important thing for people to realize, according to Shinall, is that

exoneration is not as clean a process as we think it is. “The evidence

comes to light and the judge says, ‘OK, you’re free.’ It doesn’t stop

there,” she explains. “Their life doesn’t immediately start to get

better, it doesn’t immediately wipe away everything that has happened to

them for however long they were incarcerated or what they went through

during the trial or when they were originally picked up by police. A lot

of them were incarcerated when they were in their late teens or early

20s and they’ve spent, on average, 15 or 20 years in prison and it took

away a huge part of their lives and I think that’s something people

don’t realize – it’s not as clean and happy as, ‘You’re exonerated, you

can go free now.’” “The Illinois Innocence Project is a nonprofit that

for the most part has been directing its resources towards getting guys

out of prison,” says Sean Blackwell, another UIS graduate student in

social work and research intern for the project who works with Shinall.

“Many of its grants and much of its funds have been allocated toward

things like conducting DNA tests and all the other activities that are

related to getting people out of prison.” To help determine effective

ways to facilitate reentry into society, the interns have conducted

research involving making contact with exonerees throughout the state of

Illinois. “We were able to get a window into some of the issues they

were dealing with. Many of these individuals don’t know exactly how to

assimilate, resocialize, they are at a deficit when it comes to putting

together an effective resume that will work in an increasingly

competitive work environment,” Blackwell said.

There

are a few specific recommendations the research indicates will be most

effective in helping the transitions of the recently freed exonerees.

“We are finding that these individuals would benefit from having a

mentor,” Blackwell said, “somebody to help them navigate through the

society when they get out, help them figure out everything from catching

a bus to getting on the internet, to making copies, to programming a

cellphone – things that many of us take for granted but which they were

out of the loop for and so were unable to learn.”

Blackwell also reported that their research indicates that

exonerees should receive a psychological evaluation within the first 72

hours of being released, “just to get a baseline of where their

psychological state is and see if they need any help moving forward from

there.” In addition, and just as importantly, financial literacy

counseling is recommended, to give them some insight into things like

how to open a checking account, how to save money and other ways to keep

their heads above water.

“They

are extremely vulnerable when they first get out of prison,” Blackwell

said. “The exoneration process is not a cut-and-dried, standardized

process.

“It’s a

learning period and each day brings new problems,” said Palmer, “but all

in all, it’s great. I’d rather be dealing with things on this side than

back in there. The biggest battle is with self, anyways.”

Contact Scott Faingold at [email protected].