Mentally ill inmates clog jails. Sometimes they die.

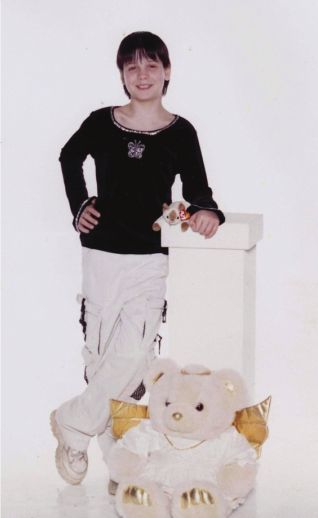

Tiffany Ann Rusher could be a handful. She was nonetheless loved.

In Rusher’s final days, relatives gathered at St. John’s Hospital. Her mother, Kelli Andrews, rubbed Rusher’s stomach and feet in the intensive care unit, hoping to evoke a response, if only a twitch, from a daughter on life support whose last of many suicide attempts would ultimately prove successful.

She didn’t come close to finishing high school, but Rusher made friends quickly and could, almost instantaneously, invent rap rhymes that would put you in stitches. Her brothers remember her as a sister who took no sass. If someone said something that Rusher didn’t like, she didn’t hold back. As a seventhgrader, her brothers say, she once responded to an insult by pushing a classmate down steps. When she was a toddler, her brothers once set her hair on fire.

“She could scrap,” Andrews says. “She was a force to be reckoned with. We taught her how to fight at an early age.”

Rusher grew up in Clinton, where life didn’t get easier as she got older. There were several brushes with the law, and Rusher’s combative demeanor didn’t serve her well in jail, where she landed for such offenses as underage drinking, battery, disorderly conduct and forgery. At 18, she smacked a fellow inmate in the DeWitt County jail, then began jumping into a closed door, which she also kicked. For her own safety, guards strapped her down in a restraint chair.

By her late teens, her family says, Rusher was addicted to crack, making frequent trips to Decatur to get drugs and sell herself to pay for them. Somewhere along the line, she became HIV positive, her mother says. In 2011, she ended up in prison and on the state sex offender registry after performing oral sex on three boys, ages 12, 14 and 15. Police reports aren’t clear on how much the boys paid – it was somewhere between $10 and $30. Sentenced to five years, she was 21 years old, and things went from bad to worse.

While in prison, Rusher attempted suicide, and it wasn’t the first time, according to her family. She was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder, according to her family and her lawyer, Alan Mills. With the Illinois Department of Corrections lacking means to properly care for mentally ill inmates, she spent months in an isolation cell, Mills says. A guard was stationed outside her cell 24/7 to prevent another suicide attempt, Mills said, and when Rusher wanted to read, the guard would hold a book up outside her cell, turning pages when she indicated.

Rusher became a potential witness in a lawsuit against the Department of Corrections filed by Mills and other Chicago attorneys who argued that the lack of mental health care for inmates was unconstitutional. Her family remembers that Rusher was determined to force the state to improve care for mentally ill prisoners. “I’m going to own this bitch,” her brothers and mother recall her saying. It never got that far. The state settled the case and Rusher finished her sentence last May. But she never would be free.

“Probably not the best place for them”

Rusher’s case underscores what sheriffs across Illinois say about mentally ill people who end up in the criminal justice system. Jails aren’t equipped to handle inmates with serious mental illness, sheriffs say, but are nevertheless repositories for troubled people with nowhere else to go. Typically, they’re accused of relatively minor crimes: trespassing, damage to property, shoplifting, assault or battery without serious injuries. And they can languish in jail for months while the system figures out what to do with them.

Rusher ended up in the Sangamon County jail after a fight at McFarland Mental Health Center, where she was committed last spring following her release from prison. After months in a prison cell with scant treatment for her mental illness, Rusher was hardly prepared for the street. If all went well, McFarland would serve as a transition of sorts, a place where Rusher could receive treatment and prepare for life on the outside.

At McFarland, phone calls were easier than in prison. Rusher could also visit more freely and frequently with her family, who brought her clothing and food that she could only dream about in prison. McDonalds was her first request. Her grandmother also delivered a feast from Golden Corral.

But Rusher reverted to old ways. On Dec. 8, she took offense at something a fellow patient said, according to a state police report. “They probably called her crazy,” her mother speculates. “She would have said ‘You want to see crazy? Come here – I’ll show you crazy.’” Whatever it was, Rusher attacked, and hard. She had a broken leg at the time – it’s not clear how the fracture occurred – and used her cast as a battering ram against the patient who had offended her, state police reported. Two McFarland employees also were injured, one seriously enough that she lost consciousness and was taken to Memorial Medical Center. When another patient tried to hold Rusher back, she bit his arm and drew blood.

“Rusher stated that she hurt multiple people and will continue to hurt people because she doesn’t want to be at McFarland Mental Health Center,” a state police officer wrote in his report.

Rusher got her wish. Mills called a week or so after Rusher was booked into the Sangamon County jail. Tiffany’s in solitary confinement, doped up on Thorazine, Mills told me. The county jail, he said, isn’t the right place for her.

The Sangamon County sheriff’s office doesn’t necessarily disagree.

“We’re seeing a huge increase in crimes committed by the mentally ill,” says Chief Deputy Joe Roesch of the Sangamon County Sheriff’s Office. “Jail is not a good place to treat the mentally ill, but once they have a charge against them, we can’t release them.”

Roesch said he doesn’t have precise statistics on just how many inmates in the jail have mental health issues, but the percentage of inmates who receive psychotropic drugs serves as a rough barometer. In 2014, Roesch said, 10 percent of the jail’s inmates were prescribed psychotropic drugs. In 2015, the percentage shot to 22 percent. The department is still compiling numbers for 2016, Roesch said, but through the first six months of last year, 12 percent of inmates were given drugs intended to treat such maladies as anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. On Feb. 10, a day picked at random by Illinois Times, 55

inmates, or 15 percent, were taking psychotropic drugs ranging from

Thorazine to lithium to Prozac in the Sangamon County jail, with as many

as five different psychotropic drugs prescribed to a single inmate,

according to records provided by the jail.

Sangamon

County isn’t alone. In Pike County, Sheriff Paul Petty says that four

or five inmates at any given time are mentally ill in jail, where as

many as eight inmates can share a single cell. The jail in Pittsfield

lacks an outdoor recreation yard – inmates can remain locked up for

months without any chance for fresh air. “They do a lot of pacing,” says

jail administrator Jordan Gerard when asked how inmates get exercise.

Petty acknowledges the quarters are tight. “If you think the walls are

close in, think of it after 10 days,” the sheriff says. “The reality of

it is, you can go ape-shit crazy in there.”

The

Pike County jail has one cell designed to prevent suicides, and Petty

says that he might add a second. Psychotropic drugs are a last resort.

So is the jail’s restraint chair.

“In a chair, strapped down, is probably not the best place for them,” Petty allows.

But

Petty sees little choice for inmates who have lost control to the point

that they pose a threat to themselves or others. Putting inmates on

suicide watch in an isolation cell, where they’re supposed to be checked

at least once every 15 minutes, only goes so far, he says.

“That doesn’t help with the screaming, the yelling, the seeing things,” Petty says. “That’s when we start bringing in pastors.”

On

April 15, the day after I visited the Pike County jail, Lafayette

Scoggins, 20, hanged himself in the cell designed to prevent suicides.

Booked on suspicion of domestic battery the day before he died, Scoggins

was in the isolation cell because he’d told jailers that he’d tried to

kill himself two days earlier by swallowing a bottle of pills, Petty

said. Guards found him hanging by his shirt, which he’d torn up and tied

to an air grate, the sheriff said. He’d been to jail before. “He was,

absolutely, a kid we knew,” Petty says. Guards called him Tad, short for

Tadpole. He was on parole for a theft conviction, and the Illinois

Department of Corrections had issued a warrant to return him to prison.

The sheriff figures he didn’t want to go. Illinois State Police are

investigating the death, Petty says. Meanwhile, the sheriff’s office is

contemplating ways to make the isolation cell more resistant to

suicides. “That’s the question we’re asking ourselves,” Petty said. “Is

there a foolproof scenario?” While jails may not be the best place for

mentally ill people, sheriffs are nonetheless responsible for their

safety. Last month, U.S. District Court Judge Richard Mills ruled in

favor of the family of Dennis E. Adams, who hanged himself in the

Christian County jail in Taylorville six years ago. Adams was arrested

after a standoff that began when he shot his estranged wife in the

shoulder, then pointed the gun at his own head. Before he was booked

into jail, a mental health professional diagnosed Adams with a

depression disorder and a doctor recommended that the jail take measures

to prevent suicide and provide treatment for mental health issues.

Adams

was put in a padded cell designed to prevent suicides, and a mental

health professional who evaluated him a week later recommended that he

stay there. Dr. Terry Killian, a psychiatrist retained by the court to

determine whether Adams was mentally fit to stand trial, recommended

that he be transferred from jail to a mental health facility for

evaluation and treatment. During a deposition, Killian testified that he

believed Adams was suicidal. Despite Killian’s report recommending a

transfer to a mental health facility, Adams stayed in jail.

Instead

of remaining in the padded cell, Adams was transferred to an isolation

cell, and then to general population. On Nov. 4, 2011, hours before he

was due in court for a proceeding in a divorce case filed by his wife,

Adams hanged himself. He had spent 78 days in jail, at least two

physicians considered him at risk for suicide, yet Adams received no

treatment for mental illness while in jail, even after a psychiatrist

recommended that he be sent to a mental health center, according to

Judge Mills’ March ruling in a lawsuit filed by Adams’ kin.

In

court documents, the sheriff’s office says it has limited resources and

competing priorities. The jail had just one padded suicide cell,

according to court records, and that cell went to a woman who was

arrested after Adams, who had to be moved to make room for her. The

woman had a documented history of mental illness and had told jailers

that she’d attempted suicide three times in the three months before her

arrest. Still, the padded cell was empty when Adams killed himself.

In

a memo to Christian County Sheriff Bruce Kettelkamp written a month

after the tragedy, jail administrator Andrew Nelson wrote that jailers

decide who should be housed in the padded cell based on “immediate

need.” That didn’t impress Judge Mills, who ruled last month that the

sheriff’s office fell short in its responsibility to keep Adams safe,

and it’s up to a jury to decide the amount of damages.

“The

‘immediate need’ as defined in their policy is determined by

correctional officers, the jail administrator and the chief deputy,”

Mills wrote in his decision. “No one in the Christian County

Correctional Center was a trained mental health professional. … The

written policy did not address most of the basic components of a suicide

prevention policy.”

Court

documents indicate that settlement discussions are underway. Neither

Kettelkamp nor other Christian County sheriff’s officials could be

reached for comment.

Delays in treatment

Given

Rusher’s background, it wasn’t surprising that Sangamon County Circuit

Court Judge John Madonia in January ordered a psychiatric evaluation to

determine whether she was fit to stand trial. At that point, Rusher had

been in the Sangamon County jail for nearly three weeks, charged with

battery for attacking patients and staff at McFarland.

Rusher

said nothing during two court appearances in February. Both times, she

was dressed in a suicide smock, known as a turtle suit by jailers.

Lacking sleeves or legs, a turtle suit is little more than a padded

blanket with a hole cut in the center for the inmate’s head. Rusher’s

hands were shackled to a thick leather belt that cinched the turtle suit

around her waist. Reports on the results of fitness examinations are

supposed to be complete within 30 days of judges ordering mental

evaluations. The report on Rusher, which should have been finished by

Feb. 5, was late. On Feb 16, Judge Madonia granted a one-week

continuance after being told that the report from Dr. Killian wasn’t

ready. One week later, the report still wasn’t ready.

“Is

she in the custody of DHS (the state Department of Human Services) or

the sheriff?” Madonia asked during a Feb. 23 hearing that lasted less

than two minutes. Told that Rusher was in jail, not a state mental

health facility, Madonia murmured, “That’s unfortunate.”

During

the past three years, Roesch says that it has taken an average of six

weeks to find beds outside the jail for inmates who require inpatient

mental health care. In the meantime, employees of Advanced Correctional

Healthcare, which holds the contract to provide health care for Sangamon

County inmates, do their best to help mentally ill inmates cope. Mental

health professionals visit the jail four times a week. It’s as much

talking as anything else, according to Lydia Hicks, regional mental

health manager for Advanced Correctional Healthcare. For example,

inmates who ask for sleeping pills often are told to lay off coffee and

daytime naps. Mental illness is often intertwined with addiction, Hicks

says, and figuring out which inmates truly need psychotropics and which

prisoners simply want pills to help dull the experience of being in jail

can be tricky.

“I think functioning is what we want to keep people doing,” Hicks says.

Many

small jails in central and southern Illinois have no formal contracts

with experts to provide mental health care. And small jails are as prone

as any other to suicide attempts and other issues with mentally ill

inmates. The 53-bed McDonough County jail in Macomb, for instance, has

had 16 suicide attempts since 2012, none successful. McDonough County

Sheriff Rick VanBrooker recalls times when half the inmates in his jail

have been on psychotopic drugs.

“It’s a real problem,” VanBrooker says. “We do the best we can with what we have.”

Economies

of scale were evident during an April 6 hearing before the State House

of Representatives Mental Health Committee. Nneka Jones Tapia, a

psychologist who is the director of the Cook County jail, told

legislators that her facility provides therapy and psychiatrists for

more than 2,000 inmates who are locked up at any given time. The Cook

County jail has also opened a post-release clinic in hopes of keeping

former inmates out of jail. There is even a gardening program that gets

mentally ill prisoners out of cells and into the community. In McLean

County, where as many as 30 percent of the inmates in the 225-bed jail

in Bloomington are mentally ill, the sheriff’s office is working on a

32-bed expansion project that will create space for mentally ill

inmates.

“We’re not

equipped for mental health,” McLean County Sheriff Jon Sandage told

legislators at the hearing. “Right now, we have them housed in our

booking area. Our booking area is loud, the lights are bright. It’s not

conducive for someone who’s having a mental health crisis to get

better.”

Wayne County

Sheriff Mike Everett and Richland County Sheriff Andrew Hires told

lawmakers the situation is worse in smaller counties.

“It’s a struggle all across southern Illinois,” Hires said.

The

32-bed Wayne County jail in Fairfield is two hours from the nearest

psychiatrist, and Everett told lawmakers that his staff has neither the

training nor the room for mentally ill inmates. It can take more than

six months to find beds in mental health facilities after it becomes

clear that prisoners need help that the jail can’t provide, Everett

testified. In one recent case, he said, a mentally ill man arrested on

July 13 of last year didn’t get transferred to a state mental health

facility until Feb. 27. A case from 2012 so affected the sheriff that he

called the inmate by his first name.

“We weren’t sure what to do with Paul,” Everett testified. “He was an extremely lowfunctioning individual.”

Paul

got arrested after striking another resident in the group home where

both men lived. He was evaluated for mental issues six days after his

arrest, then spent the next seven months in jail before the sheriff’s

office, with the help of a mental health advocacy group, found a bed in a

hospital. “We had to put him in medical isolation for his own safety

and the safety of some of the other inmates,” Everett said. “The poor

guy, I felt so sorry for him, because he did not need to be with us. He

was not a criminal. He needed help.”

Within

30 days of a judge finding that a defendant is unfit to stand trial or

is not guilty by reason of insanity, the state Department of Human

Services is supposed to take custody of inmates. But DHS often blows the

deadline. According to a 2013 DHS report, the agency missed the

deadline 305 times in a single year for 558 inmates who were deemed

unfit to stand trial. The department has 1,200 forensic beds, the same

number it had in 2013, Sharon Coleman, deputy director for forensic

services for the DHS division of mental health, told lawmakers at the

April 6 hearing. The department, Coleman told lawmakers, is under

“enormous pressure.”

“Over the years, our forensic population has increased, and the number of inpatient beds hasn’t increased,”

Coleman testified. “It doesn’t necessarily always meet the need for the

number of referrals we have coming in. We work very hard to get people

admitted within a timely manner. We triage folks, particularly if

they’re deteriorating in the county jails.”

The final days

Rusher’s

case in Sangamon County languished not through any fault of the state.

Rather, delays in writing up the results of a courtordered psychiatric

examination postponed proceedings – if Rusher was a priority for the

system, it wasn’t apparent. On March 2, the report that had been due

nearly a month earlier was filed. Rusher, Dr. Killian found, was fit to

stand trial, meaning that she was able to understand the charges and

capable of assisting in her defense.

But

that didn’t mean that Rusher, who had voluntarily committed herself to

McFarland, wasn’t mentally ill. With the jail not eager to house

mentally ill inmates and DHS not obligated to take Rusher in, the

question became what to do with her.

Robert

Scherschligt, the county public defender, told prosecutors that Rusher

would plead guilty in exchange for probation. According to a memo placed

in Rusher’s file at the state’s attorney’s office, John Morse, an

assistant state’s attorney in charge of the case, wanted to be sure that

Rusher had a stable residence before prosecutors let her out of jail.

Owing to her status as a sex offender, she couldn’t stay with relatives

in Clinton because they lived near a school. On March 15 she gave

prosecutors a name. Richard Lenchner, Rusher said, will take me in.

Old enough to be her grandfather, Lenchner, who was once a small-town police officer, knows Rusher’s story as well as anyone.

When

Rusher, exhausted from crack binges and hours of prostituting herself,

needed a ride home to Clinton from Decatur, she would call Lenchner.

When she tried to kill herself by cutting her wrists or swallowing a

ballpoint pen, she told Lenchner about it – he remembers four or five

attempts. He remained her friend even when she and one of her brothers

hid a firecracker in a cigarette that blew up in his face. He visited

her in prison.

When she needed money, he’d open his wallet, even though the cash would probably end up with a drug dealer.

“Did I enable her? Yeah. Did I want to?

No,”

Lenchner says. “I thought the world of Tiffany. I really did. My dad

dropped dead in front of me when I was eight years old. I’ve seen the

hard side of life. My whole damn family is gone. Tiffany, if you could

have ever known her, had a lot of good in her. She brought a lot of joy

into my life. If you were around her for 10 minutes, she was infectious.

She would win you over. She had that manner about her.”

And

so Lenchner agreed to give Rusher a room in his house. He didn’t know

what her future held, but he knew that she was in a deep hole, a

registered sex offender with serious mental illness who didn’t have a

high school diploma or GED or work history. He says that he talked with

the Clinton police chief before deciding to take Rusher in. “He said,

‘It’s not going to be easy,’” Lenchner recalls. “And I said ‘I know

that.’ There’s no way I could have promised a positive outcome at the

end. But I would have given it a try.”

On

March 17, the state’s attorney’s office agreed to the plan. Rusher’s

lawyer contacted the prosecutor: Instead of waiting for a scheduled

March 29 hearing, let’s move things up and get her out of jail on March

20. The hearing never happened. On March 18, Rusher was found hanging in

her cell and rushed to St. John’s Hospital. She died on March 30,

shortly after she was removed from life support.

Lenchner

doesn’t have good words for the system. A crack addict who sells her

body for drug money isn’t a true sex offender, even if the johns are

underage, he says. In prison, the Department of Corrections made things

worse by putting her in isolation instead of treating her mental

illness.

“With her,

they just slammed her ass in a cage and closed the lid – they didn’t

want to deal with her,” Lenchner says. “This thing could have been

handled so damn differently. It was one hell of a nightmare, for a long

time.”

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].