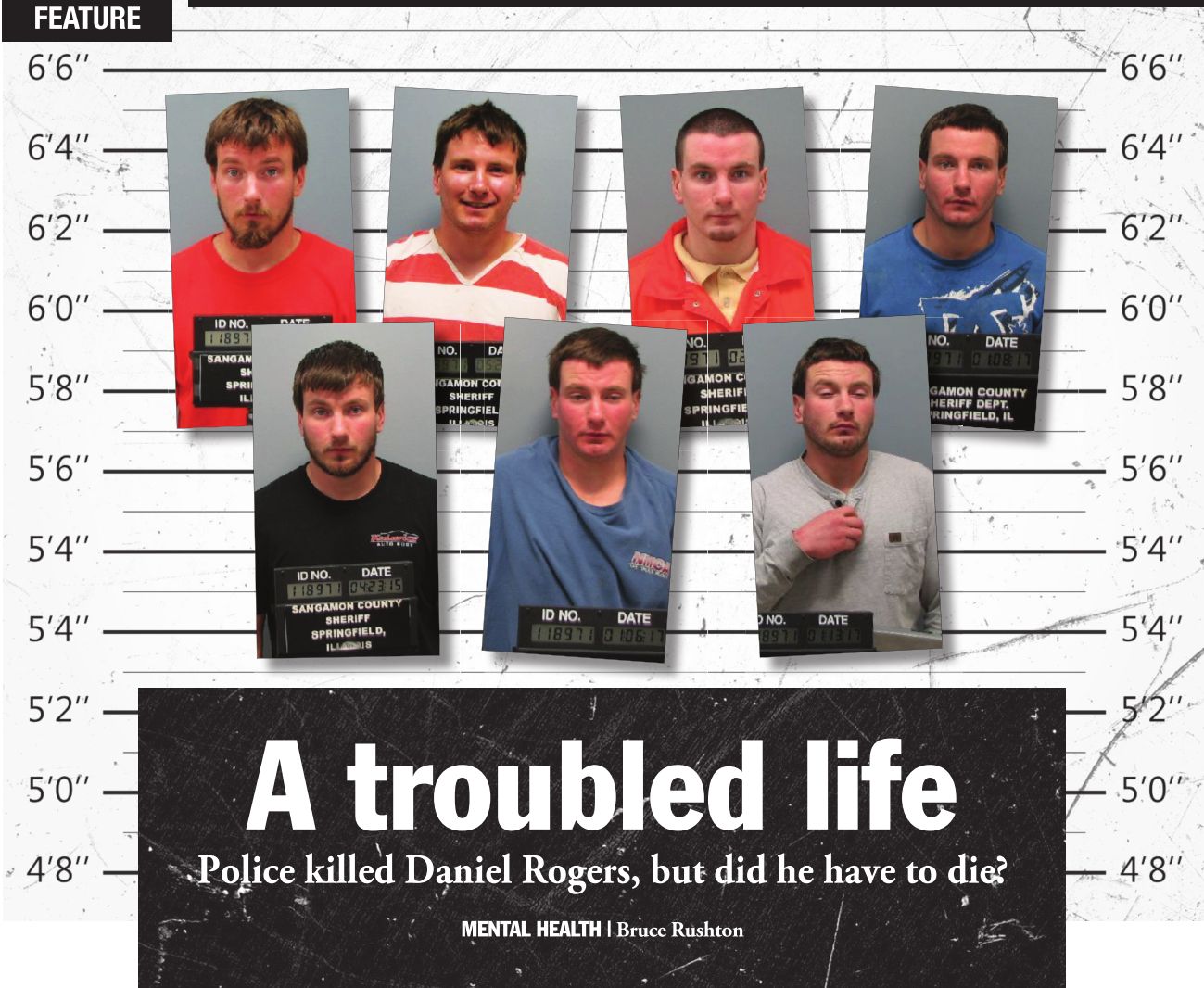

Daniel Rogers wasn’t dealt an easy hand.

He was a roofer cursed by bipolar disorder.

His father is an alcoholic with acknowledged mental problems. Rogers’ mother reportedly has Alzheimer’s disease and lives in a nursing home across Carpenter Street from where her son lived with his father in a ramshackle house.

Rogers, 27, was alternately violent and calm, the sort who would threaten to kill, then comply when cops told him to put his hands behind his back, according to records documenting numerous run-ins with the law. By all appearances, Springfield police officer John Shea underestimated the situation when he tried to arrest Rogers in January.

Rogers’ behavior was sufficiently worrisome that employees of the nursing home were warned to be careful. Records show that police had arrested Rogers three times in the space of a week at the house where he sat when Shea arrived. Jail and mental health centers proved revolving doors, and so it was up to police to handle a powder keg.

The result was tragic. Even as the handcuffs went on, Rogers made threats, and he made good on them, pummeling the officer and giving Shea little choice but to shoot.

After an investigation by Illinois State Police, Sangamon County State’s Attorney John Milhiser has declined to file charges against the officer. Police chief Kenny Winslow, citing the possibility of litigation, won’t talk about the case. But records raise questions about whether the tragedy could have been prevented.

A history of mental problems

In 2013, officers who responded to an accident to the intersection of South Grand Avenue and MacArthur Boulevard found Rogers sitting on a porch. Another man was standing in a yard. Both had blood on their clothes.

The man told police that he’d been rearended by Rogers. When the man got out of his car to check for damage, Rogers went berserk, according to reports.

“Come on!” Rogers told the man. Then he charged and began throwing punches. As an officer was talking to the man, Rogers approached. Stay where you are, the officer ordered. Rogers kept coming.

“Rogers was gritting his teeth, had his fists clenched and slightly raised, above his waist, and was scowling at me,” the officer wrote. Rogers kept advancing, threatening punches. Twice, the officer pushed Rogers back. Then police pulled Rogers to the ground and put him in a patrol car. He tried pulling away as handcuffs went on.

Rogers kicked out the passenger side rear window. “I’ll kill you fucking niggers!” he shouted. Then he began pushing the driver’s side window with his head and shoulders until it shattered. Rogers forced his way through broken glass, kicking and threatening to kill people. Officers summoned an ambulance that took Rogers to St. John’s Hospital, where he was given drugs to calm him down.

“His eyes were glazed over and he appeared high on an unknown drug,” an officer wrote in a report.

Charged with battery, resisting police and destruction of property, Rogers spent four months in jail before he was found mentally unfit to stand trial. He was sent to Chester Mental Health Center, where he recovered enough that he pleaded guilty to misdemeanor battery and was released 10 months after the incident.

Rogers

next came to the attention of Springfield police a year later, when

officers found him driving erratically on South 23 rd Street.

Rogers

seemed confused, an officer wrote in his report, and was so incoherent

that he could not use his phone when an officer asked that he call his

family. Police learned that someone had called 911 to report that Rogers

had been eating pills and talking to goats before driving off.

Rogers

told police that he’d been taking too much Depakote, a drug commonly

used to treat seizures and bipolar disorder, because he was bored. With

an officer riding along, an ambulance took Rogers to St. John’s

Hospital, where he was involuntarily committed.

Two

weeks later, Rogers was arrested for stealing vodka, beer, cigars and

cigarettes from the Northender on North Ninth Street. Police reported no

problems when taking him into custody. After being released from jail,

he failed to appear in court, and a bench warrant was issued. Someone

called 911 a few months later, reporting that he was driving through a

yard in Cantrall. Five deputies were dispatched. They arrived knowing

that Rogers could be trouble, dispatch records show.

“Subject

has been known to fight with officers in the past and drive around with

a compound bow and hammer in the vehicle,” deputies were told while en

route. Deputies served the bench warrant without apparent trouble.

A downward spiral

On Dec. 14, 2016, Rogers checked himself into Memorial Medical Center, where a psychiatrist called police.

The

psychiatrist told an officer that Rogers had threatened to kill his

father and an uncle with a hammer. Rogers admitted the threats, but told

an officer that he didn’t intend to carry them out. Nonetheless, an

officer checked the house that Rogers shared with his dad to make sure

no one needed help.

On

Christmas Eve, Rogers showed up at The Mosaic, the nursing home where

his mother lives that is across Carpenter Street from the house where

Rogers lived with his father. Rogers tried getting food from the staff

and also attempted to kick a nurse, according to a police incident

report. Police found him on his porch across the street, ordered him to

stay away from the nursing home and then left.

Rogers

was arrested after he returned to the nursing home shortly after 3:30

a.m. on Jan. 6. He was at his house when police arrived and told

officers that he’d gone to the nursing home to use a phone book. He was

released after two hours in jail.

Two

days later, police were back at Rogers’ home on a disturbance call.

With an officer present, Rogers began acting up when his father told him

that he should check himself into Memorial Medical Center for

psychiatric treatment.

“Daniel

became agitated and asked me to shoot him in the head,” an officer

wrote in his report. Rogers also threatened to punch his father. When

his father stated that Rogers often said that he wanted to kill himself,

Rogers grabbed his dad’s throat.

“I’ll

kill you!” Rogers yelled. An officer pushed Rogers away. He was booked

for domestic battery and released from jail two days later.

Milhiser

says that Rogers’ father didn’t want to press charges, and so none were

filed, but Rogers pleaded guilty to trespassing in connection with the

nursing home incident before he was freed. Milhiser says that he spoke

with Rogers before he left the jail and told him that he needed

psychiatric help. Sangamon County Associate Judge Rudolph Braud accepted

the guilty plea, and Milhiser said that the judge also told Rogers to

get psychiatric help. But advice from the prosecutor and judge fell

short of enforceable orders.

“After

talking with Daniel Rogers, I talked to the mental health center (at

Memorial Medical Center) and told them to expect him to show up,”

Milhiser says. “And they were waiting for him to come over there.” But

Rogers apparently didn’t show up.

Three

days later, on Jan. 13, Rogers was arrested again for domestic battery.

He was taken into custody after his father showed up at Memorial

Medical Center with abrasions and bruises. He told police that his son

had stomped on him and beaten him with a tree branch. A relative told

police that Rogers had been acting erratically during the past two months and was starting fights with his father.

Police

who arrested Rogers at his home reported that he tensed up as he was

being handcuffed and began pulling away. But he otherwise didn’t resist.

After four days in jail, he was freed, with no charges filed. One week

later, he was dead.

A fatal encounter

Before

they headed out for a smoke break on Jan. 23, a co-worker at The Mosaic

had warned two nursing aides to be careful. There was a guy outside,

threatening people.

Rogers

approached and asked for a lighter when the aides crossed the street to

the side where he lived. One of the aides saw that the hand-rolled

cigarette that Rogers had just lit didn’t look in good shape, so she

gave him one of hers. He put the lit cigarette in his pocket. Be

careful, one of the aides told him – you don’t want to catch your

clothes on fire.

“I want to kill myself every day,” Rogers responded.

“When

he said he wanted to kill himself every day, we was looking at each

other saying, ‘Yeah, that’s the guy,’” one of the aides later told state

police. But the aide said that Rogers didn’t appear dangerous. He said

“thank you” for the cigarette and sat back down in the wheelchair he was

using.

“He was soft spoken,” the aide told state police. “We never felt threatened by him, so I never gave it much thought.”

Video

from a surveillance camera on a nearby house shows Rogers kicking

something. A supervisor at the nursing home told investigators that it

was a basketball, which Rogers would kick so hard that it went over

houses, only to be retrieved and kicked again. Then Rogers started

digging at the ground.

“(H)e

bent over like a dog and was raking leaves and sticks out into the road

(with his hands) between his legs, backwards,” the supervisor told

police. Video from the surveillance camera shows Rogers pushing leaves,

dirt and other debris into the street with such force that an entire

lane is covered nearly to the centerline.

A

few drivers honked, perhaps after sticks or other debris struck their

vehicles. Eventually, Rogers retrieved his basketball and threw it at

the supervisor and a colleague who were in the nursing home parking lot

across the street.

A

nursing home administrator had told the supervisor to be careful

because Rogers had threatened someone with a stick or a “shiv,” state

police reported. But the supervisor didn’t sense trouble. He retrieved

the basketball as Rogers approached in a wheelchair, rambling and

mumbling. When he was five feet away from the supervisor, Rogers asked

about his ball. The supervisor rolled it to him. Then Rogers spoke.

“The

thing I distinctly heard him say is that he didn’t have no problem

stabbing or killing anyone in front of my mom’s house,” the supervisor

told police. Rogers then wheeled back across the street.

Police

were called shortly before 10:15 a.m. There was a man at the corner of

Walnut and Carpenter streets, throwing things at cars. A dispatch log

shows that police were told he was a possible 10-96, police jargon for a

mentally ill person.

“Caller

says he lives on Carpenter and is crazy,” the log reads. “Talking about

spirits. Making gun gestures with hands. Keeps getting in a neighbor’s

wheelchair and going in roadway.”

Shea and an officer in another car responded.

After

checking for four minutes and finding nothing amiss, they departed.

Three minutes later, dispatch reported that the man again was throwing

rocks at cars. Shea came back.

“He’s

in a wheelchair in front of his house,” Shea told a dispatcher as he

parked. It’s not clear how Shea knew where Rogers lived – the officer

told state police investigators that he had had no previous dealings

with Rogers.

“He’s got

a tire iron and he’s swinging it at me, getting ready to throw it at

me,” Shea told dispatchers as he prepared to get out of his car. “Ah, he

threw the tire iron at me. Start me a couple more units.”

With

backup en route, Shea got out of his car. He wrote in his report that

he believed that there was a “real possibility” that Rogers would attack

him or people across the street in the nursing home parking lot.

“What

are you doing?” Shea asked as he walked toward Rogers’ house. “Why are

you throwing sticks at me?” Rogers rose from a wheelchair and appeared

to throw something violently into the ground,

as if spiking a football. Then he walked toward Shea, arms raised up

slightly at his sides, Incredible Hulk style. Shea’s body camera

captured Rogers saying something indecipherable as he and the officer

walked toward each other. In his report, Shea says that Rogers was

inviting him to fight.

“’You

wanna fight, bitch?’” Shea wrote in his report. “He puffed up and held

his arms out to his side so I could see that his chest was big and his

upper body was well defined and developed.” Shea drew his Taser, holding

it so that Rogers could see.

“No,

I don’t want to fight – calm down,” the officer said. “You’re throwing

shit at me. What’s your deal? Turn around and put your hands behind your

back.”

Rogers hopped

down from a yard and onto the sidewalk in front of Shea. He put his

hands behind his back and appeared ready for arrest. Shea holstered his

Taser.

“You just want

to go to jail?” Shea asked as he got out handcuffs. “Is that your deal?

Why?” “Because I’m frustrated,” Rogers answered as the officer cuffed

his right hand. “I feel like beating your ass. You know how bad I want

to beat the fuck out of you?” Shea never got the chance to secure the

left cuff.

Rogers spun

out of Shea’s control and landed a blow in the officer’s face, breaking

his nose. In his report, Shea writes that he fought back, but punches

had no effect.

“(A)ll I

could do was hang onto him and tuck my head down in an effort to

protect my face and let him hit the top of my head in hopes that he

would break his hand and stop punching me,” Shea wrote. “I could feel

him pulling on my duty gear and my weapon. I knew if he disarmed me he

would certainly kill me. … My vision was going gray and I knew I was

losing the fight and that I had to end this fight.”

From across the street, a nurse’s aide watched in horror.

“It

looked like he (Rogers) was trying to reach for his gun,” the aide told

state police investigators. “The poor man – he was just pounding on

him.”

His vision

fading, Shea went to the ground, drew his gun and started firing. The

first shots seemed to have little effect. “I believed he was still

coming at me, and I kept firing my duty weapon one handed and through

the fog in my head until he went to the ground and did not move and I

believed he was no longer a threat,” Shea wrote in his report. Minutes

after the shooting, Shea sounds calm on body camera footage as he tells

other officers what happened.

“I was shooting him as I went down,” Shea said. “He knocked me back, and I just kept firing.”

All

eight shots found their mark, with two striking Rogers in the abdomen,

one hitting him in an arm and five penetrating his back and buttocks.

Forty seconds after the last shot, police cars started arriving.

The

mentally ill are prone to police shootings. In 2015, at least 254 of

the 991 people fatally shot by police in the United states exhibited

signs of mental illness, according to a Washington Post report.

Rogers was the third mentally ill person to die at the hands of

Springfield police since 2002. Shea, who has received specialized

training on how to deal with the mentally ill, also pulled the trigger

in 2008, when William Geiser attacked another officer with a steak

knife.

Geiser, who had

been making crank telephone calls, had locked himself in his motel room

and refused to open the door. He didn’t like uniforms – he had once

maced a firefighter and had also threatened a security guard with butter

knives. He opened the door at the behest of a woman who knew him and

asked for a hug. When he saw an officer outside, he attacked (“Shooting

video withheld,” Feb. 9, 2017).

Shea and another officer who shot Geiser received commendations.

The aftermath

His

son, whom everyone called Dan-Dan, has been dead for more than a month,

and Thomas Rogers is drunk in his living room, a depleted half-case of

Icehouse beer at his feet and an electric Santa Claus figure turning

back and forth on a table beside him. Outside, makeshift crosses,

stuffed animals and an empty beer can are nailed to a tree at the spot

where his son was shot.

Thomas

Rogers acknowledges alcoholism and also says that he has bipolar

disorder. He doesn’t have good words for either police or psychiatrists.

Rogers said his son never stayed long when he sought psychiatric

treatment.

“He went a

few times, but they wouldn’t keep him,” Rogers says. “The doctor said

there’s nothing wrong with him. … Anybody who says they’re going to kill

someone with a hammer, what the hell are they doing letting him out?”

Was he dangerous? Thomas Rogers pauses. “No,” he answers. Then he pauses

again.

“He was dangerous. The cops already knew. They’d come here a bunch of times.”

Shea

should have waited for backup instead of trying to make the arrest by

himself, Thomas Rogers says. Why did he fire so many times, he asks. His

son was a good kid, but he had anger issues and just snapped.

“I

ain’t gonna lie: The kid made me nervous,” Thomas Rogers says. “The

only thing I’ve got to say is, he’s better off where he’s at. I don’t

have to worry about him knocking me in the head and him spending the

rest of his life in prison.”

Springfield

police won’t answer questions about the case, including whether Shea

should have waited for backup. Milhiser says that the county probation

office is hiring a mental health counselor to evaluate defendants to

determine whether they need psychiatric help. He acknowledges cracks in

the system when it comes to folks like Rogers.

“The

jail would have him, but the hospital wouldn’t keep him and family

didn’t want criminal charges,” he says. “We can do better with those

individuals who are coming to the jail with mental health issues, and we

need to do better.”

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].