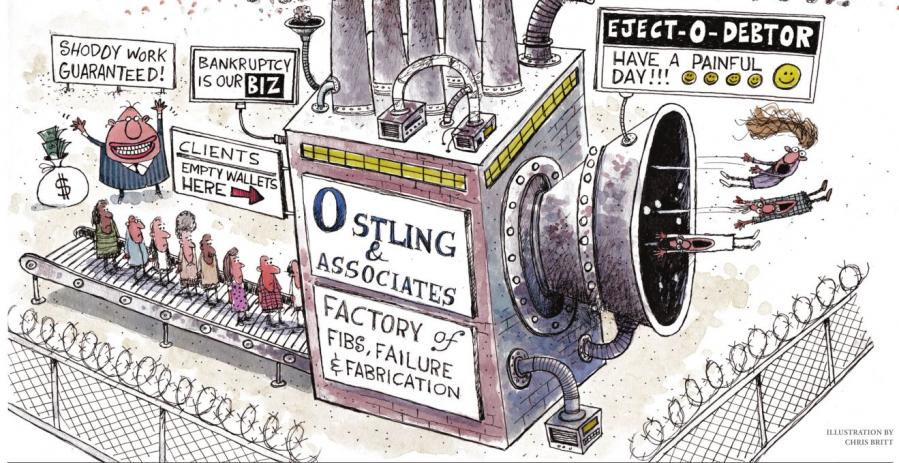

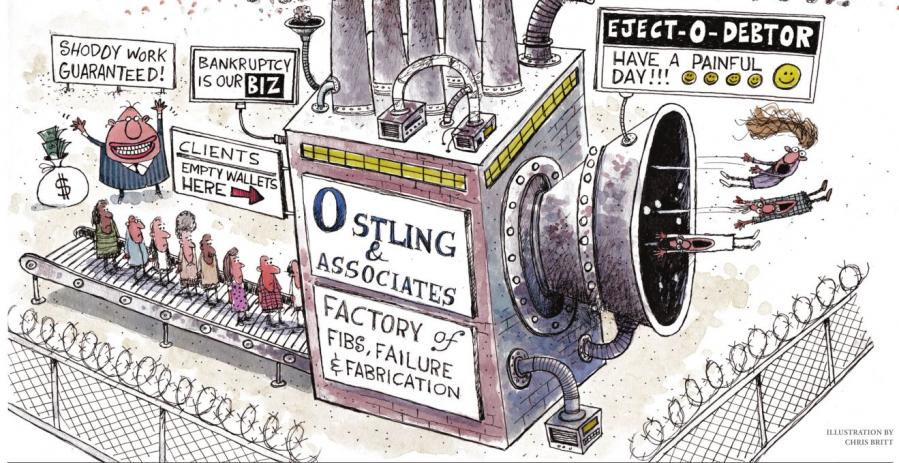

In television ads and on the internet, Ostling and Associates boasts that it is Illinois’ largest bankruptcy law firm.

“When you need help, call Ostling and Associates,” the announcer on a television commercial urges viewers. “With 20 Illinois offices to serve you. Call Ostling and Associates now and stop the collection calls.”

The ads apparently work. The Bloomingtonbased firm boasts that it has handled more than 50,000 cases. But bigger isn’t necessarily better, judging by a series of harsh rebukes aimed at the firm and its lawyers by U.S. Bankruptcy Court Judge Mary Gorman.

From the bench in Springfield, Gorman has repeatedly called out Ostling attorneys for fibbing in court, performing shoddy work and assigning legal tasks to employees who aren’t lawyers. Clerical workers who help prepare bankruptcy filings are untrained and unsupervised, and debtors have suffered, according to the judge who has handed out penalties that include at least one fine, reductions in legal fees and prohibitions on two Ostling attorneys from filing court documents.

“I think the most heartbreaking thing of the six years I’ve spent on the bench, for me, has been the quality of work that I’ve seen come from the Ostling firm and the number of debtors who have suffered dramatically due to the pitiful, pitiful quality of that,” Gorman said during a 2012 hearing. “It is heartbreaking to see debtors go to the Ostling firm, pay good money and get representation that does not meet ethical standards or any level of quality standards.”

Judge Gorman isn’t alone in her alarm. Last year, the Illinois Attorney Registration and Disciplinary Commission suspended one of the firm’s lawyers for five offenses that included making false pleadings in Gorman’s court. The same lawyer also had a problem with alcohol that had resulted in convictions for driving under the influence, battery and disorderly conduct, the ARDC determined. The lawyer is back on the job at Ostling, but still on probation.

Problems with the firm date to at least 2009, when an attorney scheduled to appear on behalf of three Ostling clients could not be reached. Gorman’s staff tried several times to reach a lawyer. On the final attempt, the person who answered the phone at Ostling and Associates hung up on the judge’s staff.

“Clerical staff at the Ostling firm is apparently trained not to allow calls to be put through to attorneys in the office and further instructed that, if callers become too pesky by repeatedly calling, the remedy is to hang up the phone,” Gorman subsequently wrote in a ruling that did not go well for an Ostling client who had filed Chapter 13 bankruptcy in an attempt to save her home.

The bankruptcy trustee had moved to dismiss the case on the grounds that the debtor was $5,515 behind on payments to address delinquent mortgage debt. She had also fallen behind on real estate taxes. Unable to reach a lawyer at Ostling and Associates, the judge dismissed the case, opening the door for foreclosure. Ten days later, Robert Follmer, an Ostling lawyer, asked Gorman to reinstate the case, saying that he would deliver a $5,000 certified check to the trustee. He also repeated an earlier promise to file a request to amend the payment plan. But it was too late.

“Perhaps, if an attorney had appeared, details of the promised motion to modify (the payment plan) could have been provided and, if the debtor had the $5,000 that she now proposed to tender, the trustee might well have been persuaded to seek continuance of his (dismissal) motion,” Gorman wrote in rejecting Ostling’s efforts to revive the case. “But, the debtor’s attorney failed to appear and, unfortunately for the debtor, she is bound by both the acts and omissions of her attorneys.”

It was not an isolated instance, the judge observed.

“This court has heard numerous complaints over the years from clients of the Ostling firm and from creditor attorneys that calls placed to the Ostling firm are never put through to attorneys and are never returned,” Gorman wrote in her dismissal order. “Such a policy is unprofessional at best and, as was made painfully obvious here, extremely detrimental to the clients of the Ostling firm.”

Illinois Times left telephone messages for several Ostling lawyers, including managing partner Lars Eric Ostling, to get responses to Gorman’s criticisms. The messages were not returned.

“Somewhat of a joke” According to her testimony in Gorman’s court,

Monica Lynn Moffett of Lincoln would not have declared Chapter 7 bankruptcy if she’d known that her creditors could take more than $55,000 that she was due to receive in three payments as part of a lawsuit settlement.

Accused by a bankruptcy trustee of concealing the money from creditors, Moffett during a 2011 hearing testified that she’d told Denise Knoles about the settlement when she first went to Ostling and Associates for help. Knoles told her that she was a candidate for Chapter 7 bankruptcy.

“I explained my situation, told her I had this money and I was very concerned about this money because I didn’t want to lose this annuity, this money,” Moffett told the judge. “And she asked me, you know, some questions about it – when is it going to be paid out, and all of this. And I told her. And after…we went through everything with my debt and she told me it wasn’t relevant because it wouldn’t be paid out until 2016 and it wasn’t something I had to worry about.”

Moffett said she thought that Knoles was a lawyer. In fact, Knoles was a legal assistant, and the settlement that Moffett wanted to protect was, under the law, within reach of creditors. An intake sheet prepared by Knoles showed the figures that Moffett was due from her settlement, but Justine Guthrie, the legal assistant who helped prepare the bankruptcy filing three months after the initial consultation, testified that she normally doesn’t review intake sheets. No lawyer reviewed the intake sheet, or met with Moffett, before she filed for bankruptcy and didn’t disclose that she was due money from a lawsuit.

Gorman refused to discharge Moffett from bankruptcy, giving creditors a shot at the settlement. Then the judge went after Larry Spears, the Ostling lawyer who had signed a declaration attached to Moffett’s bankruptcy filing stating that he had informed his client about various bankruptcy chapters and what relief the chapters could provide, even though he had never met her.

Spears and Lars Ostling himself told the judge that the Moffett case had been filed on an emergency basis with minimal information because the client wanted to stop the IRS from garnishing a paycheck. Gorman wasn’t impressed.

“His (Spears’) failure to obtain more than the basic information resulted in incorrect and false documents being filed,” Gorman wrote in a 2012 decision that skewered the entire firm. “Both attorney Ostling and attorney Spears expressed surprise that current law requires them to do an investigation of the facts of a case before filing, even when there is some claimed emergency reason to get the case on file in a hurry.”

The judge noted that Guthrie, the legal assistant who prepared the bankruptcy petition, had laughed during a hearing when asked whether she reviews intake sheets when clients return to the firm after initial consultations and retain Ostling and Associates to file bankruptcy cases. Guthrie had testified that she reviewed intake sheets only if she could find them.

“Her testimony created the impression that the intake sheets are kept in large, disorganized piles and that Ostling and Associates’ staff treats the intake sheets as somewhat of a joke,” Gorman wrote.

The judge wrote that Ostling employees were “inadequately trained and unsupervised” and that Spears, ultimately, was responsible for mistakes made by legal assistants. It wasn’t the first time the judge had warned Spears that he couldn’t blame faulty filings on others. Gorman suspended his filing privileges in bankruptcy court for six months and ordered him to undergo three hours of training on “basic consumer bankruptcy issues” and one hour of training on ethics and professional responsibility.

Suspending a lawyer’s filing privileges is a monumental punishment, according to Bruce A. Markell, a Northwestern University law professor who earned a reputation for being tough on high-volume bankruptcy law firms during his nine-year tenure as a federal bankruptcy court judge in Las Vegas, where he earned the moniker “Bam,” in part due to his initials but also for his willingness to punish lawyers for poor work. In one case, Markell wrote a 91-page opinion blasting a lawyer for inadequately reviewing a case prior to filing a bankruptcy petition, then refusing to represent the client when a creditor sued.

“Six months is a huge deal,” Markell said of Gorman’s decision to suspend Spears’ filing privileges. “I never imposed that sanction.”

Instead of charging by the hour, Ostling and other high-volume bankruptcy typically charge flat fees, a practice blessed by bankruptcy courts that would otherwise be tasked with reviewing fee, and law firms may charge that much or less without submitting itemized bills. But Markell said there’s a down side.

“That flat-fee structure provides incentives to cut costs,” Markell said. “When you cut costs, you run into some of the types of things you’re describing. … There’s no two ways about it: Sometimes lawyers lose sight of the fact that they’re in a profession, not a trade.”

Markell said that it’s not necessarily a problem if non-lawyers assist with initial client consultations, and it’s possible for high-volume bankruptcy firms to provide good service.

“It can be done,” the former bankruptcy judge said. “The trouble is, it’s cheaper to run it unethically.”

Slashed fees, false filings

At least four times since 2012, Gorman has cut Ostling’s legal fees, ruling that performance was so poor that the firm didn’t deserve standard flat fees.

After telling Ostling and Associates that it would not get the standard $3,300 fee for a Chapter 13 case due to poor legal work, Gorman in 2014 required the firm to submit an itemized bill for work done on behalf of a couple who had declared bankruptcy in an attempt to save their home. The firm, which gave Gorman a bill for $2,852, was granted just $600, with the judge ordering Ostling and Associates to give up $400 of a $1,000 retainer that the couple had already paid.

Ostling lawyers had filed inconsistent paperwork in the case, stating in one portion of a court filing that the debtors’ home would be surrendered while stating in another portion of the same filing that the debtors would pay the mortgage. Filings from Ostling had also set the value of a commercial building at zero, even after a bankruptcy trustee pointed out that wasn’t possible. It took five attempts before Ostling and Associates corrected mistakes and filed accurate documents so the case could be resolved.

“Any attorney, even one who had never met the debtors, should have the skill to review documents and spot such obvious flaws as the ones that existed here,” Gorman wrote in her decision that slashed Ostling’s fee.

The judge also doubted expenses claimed in the firm’s itemized bill. For instance, the firm charged for a lawyer to attend a meeting that had been held four days earlier than stated in the bill. Gorman concluded that the firm had made up time entries after the fact instead of relying on records created as work was accomplished, which she found “misleading and unprofessional.”

Follmer, the Ostling lawyer who filed the faulty bill, asserted that the charge would be higher than the standard $3,300 flat fee if the firm actually kept track of time. Ridiculous, responded the judge, who said that such a stance was premised on the notion that it is OK for lawyers to charge for wasted time spent preparing faulty paperwork.

“(T)he argument misses the point that if Ostling and Associates’ attorneys kept accurate, contemporaneous time records, they would soon see for themselves that they are wasting their own time, money and resources with their inefficient and unprofessional practices,” the judge wrote.

The ruling came two years after Gorman excoriated the firm and its lawyers for a bill submitted in a different case. As in the 2014 case, Gorman ordered an itemized bill in the 2012 case after Ostling lawyers filed paperwork riddled with mistakes. Ostling submitted a bill for $3,300 and told the judge that the firm’s actual costs had totaled more than $5,400. The judge didn’t believe it.

For one thing, the bill showed that Ostling lawyers earn as much as $450 per hour, an amount that the judge deemed preposterous considering the poor quality of the firm’s work and what lawyers typically charge in central Illinois. Furthermore, Lars Ostling billed for two hours of his time to review a bill that the judge determined was phony. When Gorman told Ostling and Associates to try again, the firm submitted a second bill for $3,700, saying that all the firm’s lawyers make $175 per hour. The judge cut the fee to $2,200, then levied a $500 fine for claiming false hourly rates.

“Those rates were made up and intended to mislead the court,” Gorman wrote. “This court should not have to ask twice to get truthful, accurate documents and pleadings from attorneys who practice before it.”

No Ostling lawyer had sufficient expertise to command top dollar, Gorman concluded.

“The work in this case evidenced a significant amount of stumbling and fumbling around and the attorneys needed five attempts at drafting a plan in order to bring a fairly simple and straightforward Chapter 13 case to confirmation,” the judge wrote in her decision.

“The legal work here can only be characterized as poor. And, unfortunately, this case is not an isolated incident.”

That same year, Gorman stripped an Ostling lawyer of his filing privileges in a case that resulted in the attorney being suspended last year by the state Supreme Court.

The case involved a debtor who had initially hired Ostling and Associates to negotiate with creditors. After selling property for $60,000 in 2009, the debtor gave the firm $25,000 to pay creditors, with the money being deposited in an Ostling trust account. With $13,595 remaining in the trust account in early 2011, Jeffrey Abbott, an Ostling attorney, paid $11,000 to two credit card companies at the debtor’s request, bringing the trust fund balance to $2,595. Two days later, Abbott filed a Chapter 13 petition.

Under bankruptcy law, debtors must disclose all assets and all payments made to creditors within 90 days of filing for bankruptcy, but the bankruptcy petition filed by Abbott included no mention of money in the trust account held by Ostling and Associates or the $11,000 payment to creditors made two days prior to filing for bankruptcy. It took more than a year before the truth emerged, and only after attorneys for creditors found out about the $60,000 land sale and asked where the money went.

“And how is this not something I have to refer to the U.S. attorney?” Gorman asked during a 2012 hearing, after discovering the payments and cash in the Ostling trust account that hadn’t been disclosed. “It’s just stunning. I mean, I don’t know what word to use when you see a law firm that would participate in something like this.”

During a subsequent hearing, the judge rejected Abbott’s attempts to shift blame to other Ostling employees. Gorman reminded him that he previously had blamed clerical workers for problems – during a 2009 hearing on an unrelated case, he had used the word “stupid” to describe an Ostling clerical worker whom he blamed for filing faulty paperwork. Abbott, the judge decreed, must bear the blame himself.

“This was a serious fraud on the court, and it was covered up,” the judge said. “(T)he system depends on honesty.”

Gorman suspended Abbott’s filing privileges for eight months and ordered him to complete three hours of training in basic consumer bankruptcy and an additional three hours of training on ethics. The ARDC launched an investigation that culminated with Abbott being suspended from practice by the state Supreme Court last year, after the disciplinary commission found that Abbott had made false statements to the bankruptcy court. According to ARDC records, Ostling and Associates agreed to pay claims of creditors in the case.

The ARDC didn’t stop there. In sanctioning Abbott, the ARDC found that he also had pleaded guilty to driving under the influence in 2005 and battery in 2007, the latter charge stemming from a drunken incident at his home when he slapped a man in the face and pushed a woman down when she tried to call police.

In 2011, Abbott, drunk again, began berating a neighbor from his backyard, calling her “a fucking idiot” and a “dumb bitch.” He bragged that he was a lawyer and made obscene gestures toward her and shooting gestures toward children, prompting a call to 911. Abbott was still at it when police arrived – officers arrested him after hearing him hurl threats. “I’m a lawyer that actually will fucking kick your ass,” Abbott told an officer. He also called an officer an idiot and said “Wait until I get done with you,” and “Don’t make me call you into court. Don’t. Because I will.” He pleaded guilty to disorderly conduct.

Abbott last year admitted to all allegations and agreed to a five-month suspension and two years of probation. If a disciplinary hearing had been held, the ARDC determined that other lawyers would testify that he had “a good reputation for honesty.” Abbott had been sober for a year, the commission determined, and a psychiatrist had found that he was fit to practice law “largely due to his supportive work environment.”

After serving his suspension, Abbott returned to work as an Ostling lawyer. He remains on ARDC probation.

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].