When receiving word that the Chief Magistrate is planning a visit, the hosting city is usually quick to roll out the red carpet. Not so in 1866, when President Andrew Johnson arrived in Springfield only to receive the cold shoulder from the city council and many prominent citizens.

Johnson’s visit to Springfield was part of his ill-fated “Swing Around the Circle” speaking tour around the eastern half of the United States between Aug. 27 and Sept. 15, 1866. His goal was to drum up support for his Reconstruction policies and his preferred congressional candidates in advance of the upcoming midterm elections. Along the way, however, he was met with coldness and outright hostility, especially in the Midwest.

Johnson, who hailed from Tennessee, had been the only Southern senator to remain loyal to the Union during the Civil War. In 1864, Abraham Lincoln selected Johnson as his running mate, believing that the “War Democrat” would help to balance the ticket. After Lincoln’s assassination, Johnson, a former slaveholder, implemented Reconstruction policies that were lenient to the South. He issued amnesty to former secessionists, permitted former Confederate officials to return to power in state and federal government, turned a blind eye to the restrictive “black codes” passed by Southern states, vetoed the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and opposed the 14th Amendment, which would guarantee citizenship to former slaves.

These actions enraged Republicans, who felt as though Johnson was betraying Lincoln’s legacy, pandering to Southern elites and willfully stifling the civil rights of former slaves. The midterm elections of 1866 came to be seen as a referendum on Johnson and his policies.

To shore up support for his policies, Johnson decided to embark on an 18-day speaking tour. He took along Secretary of State William H. Seward, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles and Civil War heroes David Farragut and Ulysses S. Grant to bolster his appeal.

The idea of a sitting president personally engaging in political campaigning was already frowned upon, and Johnson only made things worse for himself by departing from his prepared remarks along the way to engage with hecklers, imply treason on the part of Radical Republicans and cast himself as a Christ-like figure.

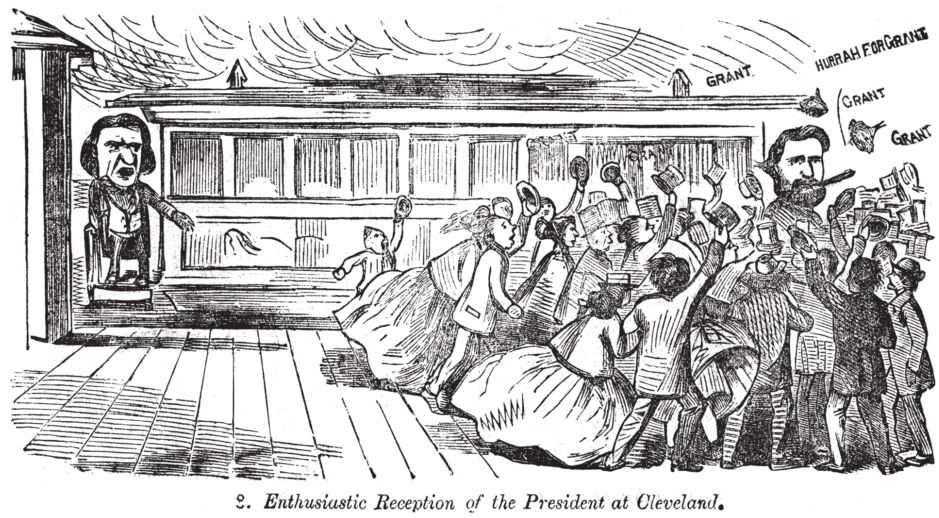

Johnson’s reception grew more hostile as he traveled farther into the Republicanleaning Midwest, though crowds continued to cheer warmly for Grant and Farragut. In Chicago on Sept. 7, Johnson received what one reporter called a “chilling reception.”

Gov. Richard Oglesby and

the Chicago city council declined altogether to be present, and Mary

Lincoln left the city for a brief visit to Springfield, deliberately to

avoid Johnson.

Meanwhile,

news of Johnson’s impending visit sparked intense partisan squabbles

within Springfield. Democrats within the city lobbied the city council

to extend to Johnson and his party a formal invitation to visit the

capital city and the tomb of Abraham Lincoln. In a breathtaking snub,

the Republican-dominated city council obliged, but struck Johnson’s name

from the invitation.

Calling Johnson a “partisan” and “demagogue,” they issued a statement in the Illinois State Journal declaring

“Our City Council, speaking the sentiments of a large majority of the

people in Springfield, have no desire to see the tomb of their martyred

Lincoln desecrated and insulted by the lowflung partisan harangues of

Andrew Johnson, who succeeded to his place only through the assasin’s

bullet.”

Local

Democrats were outraged, denouncing the council’s actions as “an

official insult to our Chief Magistrate” and insisting that “no such

outrage was ever before perpetrated in our fair city.” They sought to

assure the president that the city of Springfield “will not only invite

him, but will give him the most cordial reception he has received since

he left Washington.”

When

Johnson and his party arrived in Springfield, the Democrats had

succeeded in mustering a decent welcome for them. The presidential

party’s train arrived in Springfield at 4:20 p.m. on Sept. 7 to a

waiting crowd of some 3,000 people. A sizable crowd also waited for them

at Oak Ridge Cemetery, where Johnson journeyed to pay final respects to

Lincoln. Still another thousand people waited for them at the St.

Nicholas Hotel, where the party was staying. When Johnson addressed the

crowd, he tendered his “thanks for the cordial welcome you have given me

on this occasion.”

Republicans

in Springfield, however, were quick to assert that the city’s warm

welcome was reserved for Grant, Farragut, Seward and Welles. After

Johnson’s party moved on, the Journal concluded “A. Johnson, the

politician and scheming demagogue, was completely snubbed by the people,

while the men to whom the nation owes its salvation...were greeted in

the most joyful and cordial manner. The state and city authorities had

nothing to do with the reception of the President.”

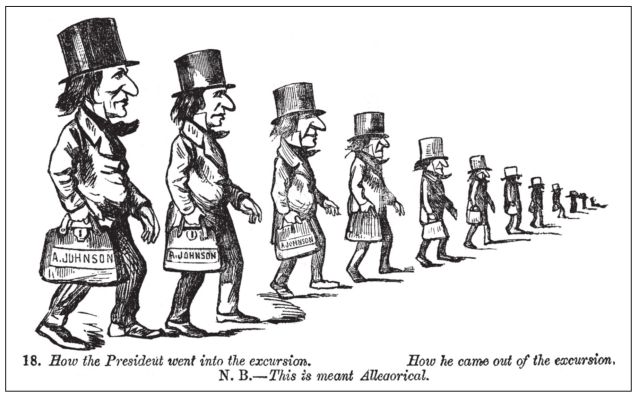

Ultimately,

Johnson’s speaking tour was roundly lampooned by the press and

criticized by Republican politicians. In the end he alienated more

people than he rallied to his cause; U.S. Sen. James Doolittle of

Wisconsin said that the tour had “cost Johnson one million northern

voters.” The Republicans won a landslide victory in the midterm

elections and thus gained control of Reconstruction policies. In 1868,

the Republican-led Congress impeached Johnson and came within one vote

of removing him from office.

Erika Holst is the author of Wicked Springfield: Crime, Corruption and Scandal During the Lincoln Era.