Writer Nelson Algren once observed that “Chicago is an October sort of city even in spring.” Fans of Chicago’s baseball teams would certainly disagree since October is the month of baseball’s World Series and in the past 100 years the city has celebrated only two baseball world championships. Whether you love the Cubs or the White Sox, you have rarely experienced the thrill of a championship parade. The Black Hawks have won more championships this decade than the Cubs and White Sox since the first World War. But this might be our year. Both teams are off to wonderful starts in this 2016 season. New ownership has transformed the Cubs into perhaps the National League’s best team. After the first month of the season, the White Sox were equally strong. The southsiders have already stumbled, but the Cubs are currently the best team in baseball. The incurable optimism of their fans might finally be rewarded this October.

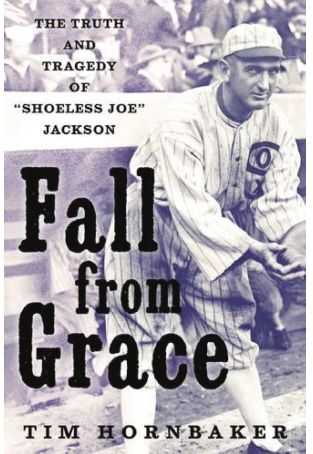

Whatever team occupies that special place in your baseball heart, baseball historian Tim Hornbaker has written an engaging biography of a different era in Chicago baseball history. Fall From Grace is the story of Shoeless Joe Jackson, immortalized in books and movies as one of the players who conspired to throw the 1919 World Series. Banned from baseball for life by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, Jackson still has a small cadre of supporters who maintain he was an innocent victim. Some supporters argue for his posthumous induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Fall From Grace is a delight. It is loaded with game and season detail and chronicles an era of baseball long before World Series night games, performance-enhancing drugs and multimillion-dollar free agents. Yet it captures the essence of the game, the team loyalty, strategy and season-long battles for victory. In the era of Shoeless Joe Jackson, players were heroes to their fans and opposition players were scoundrels. That element of the game remains unchanged.

Hornbaker traces the career of Joe Jackson from a mill-working child in South Carolina to stardom in the American League and to eventual banishment. It is an anecdote-rich story reminding us repeatedly of what we have come to love about baseball. No PEDs or weight-training for Joe Jackson. Instead he followed the advice of his first major league manager, Hall of Famer Napoleon Lajoie. When Jackson arrived at Cleveland, he discovered that Lajoie had a routine of drinking a gallon of buttermilk each day to strengthen his eyes while batting. Jackson followed suit. Apparently it worked and worked very well. In Jackson’s first full season he batted an astonishing .408 but amazingly did not win the batting championship. Ty Cobb hit .420. Jackson had 233 hits during his rookie season, a baseball record that stood for 90 years until broken by Ichiro Suzuki in 2001.

In Joe Jackson’s era, players were commodities. The major league contract with its notorious reserve clause bound a player to a team for life. Owners often sold players to raise cash. In 1915, major league baseball was challenged by a rival Federal League. Players began using the new league to bargain for salary increases and some owners were reluctant to pay their players more money. Charles Comiskey, owner of the White Sox, seized the moment to purchase Jackson from Cleveland for three players and $31,500. Comiskey was spending large sums to build his White Sox into a championship team.

Between Jackson and future Hall of Fame player Eddie Collins, he would spend close to $100,000 for players. In an era when player salaries were less than $5,000, these were large sums of money. The trade did not propel the White Sox to a championship in 1915 but they finished second in the American League and their future looked promising.

The 1917 White Sox won 100 games and defeated the New York Giants to win the World Series. The 1918 season was impacted by many players serving in the military. Joe Jackson worked in a shipyard during that season and Hornbaker notes that some fans questioned his courage for avoiding military service. But by 1919 he was back in uniform and the Sox were baseball’s best team and favorites to win the World Series against Cincinnati.

Hornbaker’s description of the events surrounding the fixing of the 1919 World Series is detailed. Unlike others he does not attempt to exonerate Jackson but often he seeks to minimize or excuse his actions. A jury acquitted the Black Sox players of criminal charges but baseball barred the players for life. Hornbaker notes that the passage of time has made Joe Jackson a legend and somewhat of a cult figure. After reading this thoughtful and informative biography, readers may take a somewhat more charitable view of Shoeless Joe Jackson.

Stuart Shiff man is a frequent contributor to Illinois Times and a lifelong Chicago White Sox fan.