Closing the nuclear power plant at Clinton

Illinois has a long history with the atom. The world’s first nuclear reactor began operating in 1942 beneath a football field at the University of Chicago, where scientists with the secret Manhattan Project were developing the atomic bomb. Illinois now has 11 commercial nuclear reactors generating electricity at six sites – the most nuclear power reactors of any state.

Still, Illinois is not fertile soil for nuclear power. A confluence of factors has caused untenable revenue losses for Illinois’ nuclear power fleet several years running. The losses are so large that the company which owns all six of the nuclear power stations in Illinois has announced plans to close two of them and may close more in the future.

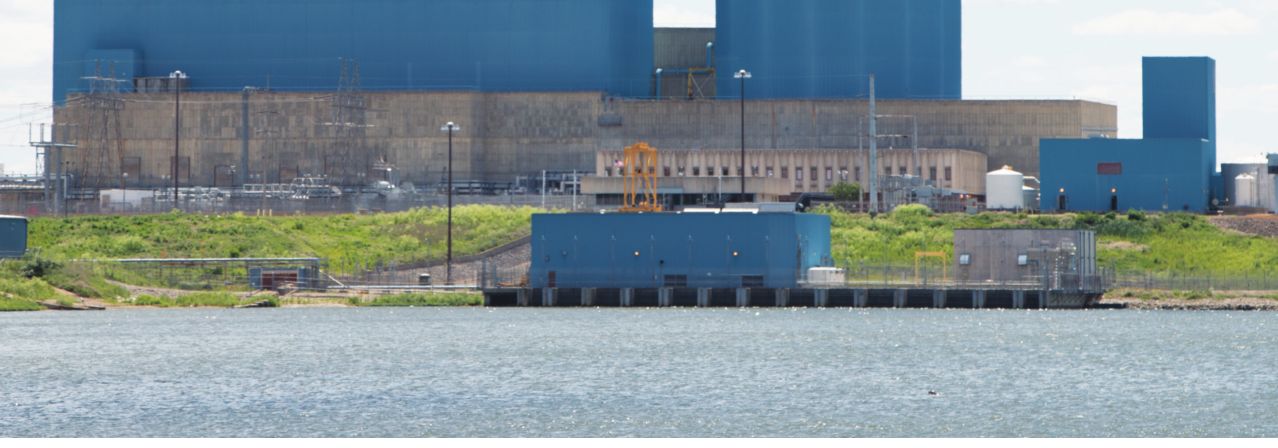

Clinton Power Station, owned by Exelon Generation, is a 1,068-megawatt nuclear plant painted sky blue and sitting on a manmade lake 45 miles northeast of Springfield.

It’s one of the two plants in Illinois Exelon plans to close and decommission – assuming Illinois lawmakers don’t approve legislation to save it. The bill has been characterized by supporters as a commonsense move to help Illinois meet its goal of reducing carbon dioxide emissions, but opponents say it’s nothing more than a bailout for an otherwise profitable company.

Meanwhile, uncertainties remain about the plant’s future, the economic well-being of the surrounding area, Illinois’ electricity market and even the radioactive material that will likely stay there for generations to come.

A troubled past

Clinton Power Station had troubles from the start. Illinois Power Company, the now-defunct energy company which began building the plant in 1975, originally intended Clinton to have two nuclear reactors and a price tag of around $500 million. The infamous Three- Mile Island nuclear accident in 1979 prompted regulators to impose new design requirements on nuclear plants being built at the time, and the cost of the Clinton plant ballooned out of control, ultimately totaling around $4.25 billion by the time it opened in 1987. Construction stopped before the second reactor was added, but visitors can still see steel reinforcement bars and concrete patches jutting out of the side of the Clinton plant where the second reactor would have been. Exelon purchased the plant in 2001 and considered adding a second reactor in 2003, but later abandoned that idea.

Exelon’s purchase of the plant was preceded by constant problems under Illinois Power Company’s ownership. It was frequently blasted for high electricity rates during the 1990s by consumer groups, and it was completely shut down for more than two-and-a-half years starting in 1996 because of safety issues that made federal regulators question whether Illinois Power placed profit over safety.

Brett Nauman, a spokesman for Exelon, says the Clinton Power Station now has a good safety record. The plant has a VPP Star rating from the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which requires rigorous site inspections by OSHA. A counter on a wall near the plant’s safety office boasts nearly three years without a “foreign material exclusion” incident which can occur when someone leaves something as insignificant as a pen where it shouldn’t be.

Following the 2011 meltdown of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Station in Japan, all U.S. nuclear plants underwent an inspection specifically to determine whether they were susceptible to a similar incident. The Fukushima meltdown happened in part because a devastating tsunami swamped the plant’s backup diesel-powered cooling pumps. Nauman says Exelon spent millions of dollars to upgrade the Clinton plant with items like additional cooling pumps in case all three of the existing redundant diesel pumps couldn’t operate.

Regulatory enforcement actions by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission against Clinton are rare. Most recently, the NRC cited Clinton Power Station in August 2015 for having an inoperable pump out of service too long. A modification made to the pump in 1995 – before Exelon even owned the plant – failed in May 2014 but wasn’t discovered until September of that year. NRC didn’t fine Exelon, and that incident is one of only four enforcement actions against the plant since Exelon took over in 2001.

Last month, the Clinton plant achieved a national record of 11 days for the shortest reactor outage due to refueling. Exelon’s announcement of the record came just one day before it announced that the plants at Clinton and the Quad Cities would close.

An unfavorable present

The current problem for Clinton Power Station and its nuclear brethren began about seven years ago, but it stems from something that happened about 20 years ago. Since 1998, Illinois has been a “deregulated” power market, in which energy companies can’t own both power plants and electricity transmission lines. “Deregulated” refers

to companies which generate electricity no longer having

government-approved monopolies in their coverage area. That means

consumers can choose which company produces their electricity, even if

they can’t choose which company delivers it to their homes.

One

result of a deregulated market is that most consumers opt for

electricity from the cheapest possible source. For many years, coalfired

power plants were the cheapest to operate, although coal’s dominance

has lately been supplanted by natural gas as environmental regulations

tighten on coal emissions and hydraulic fracturing brings previously

inaccessible pockets of natural gas to market. Compared with either

fuel, however, nuclear power is more expensive and thus less utilized.

Exelon

says its nuclear fleet in Illinois has lost $800 million since 2009,

and the company plans to limit future losses by closing the plant at

Clinton on June 1, 2017, and the Quad Cities Generating Station in

Cordova, Illinois, on June 1, 2018. Nauman, the Exelon spokesman, says

the only thing which would prevent the two plants from closing is

passage of a bill to essentially reimburse Exelon for its losses.

Different versions of the bill have failed to pass the Illinois General

Assembly repeatedly.

The

bill would create a fixed-rate surcharge on a consumer’s electricity

bill, helping counter Exelon’s operating losses on its nuclear plants.

The company would have to justify the surcharge rate to state regulators

each year.

David

Kraft, executive director of the Nuclear Energy Information System, an

anti-nuclear advocacy group, sees Exelon’s cry for help as crocodile

tears. He notes that Exelon’s parent company, ComEd, was among those

pushing for a deregulated market in the 1990s.

“At

last check there is no clause in the Illinois Constitution requiring

the legislature to guarantee the profits of a private corporation,

certainly not using ratepayer money,” he said. “It is Exelon’s stubborn

and self-centered decision-making that has led them into this literally

unprofitable situation. It would be wrong for the legislature to bail

out those detrimental corporate decisions on the backs of Illinois

ratepayers.”

The

Better Energy Solutions for Tomorrow (BEST) Coalition, a nonprofit group

of mostly businesses opposing Exelon’s bill, calls Exelon “exceedingly”

and “enormously” profitable, depicting the company as telling Illinois

lawmakers it’s losing cash while telling investors it’s doing well.

Gov.

Bruce Rauner hasn’t said whether he’d approve the Exelon bill if it

reaches his desk, although he hinted at support for the bill by saying

he was “extremely upset” when Exelon announced the Clinton and Quad

Cities closures. Meanwhile, Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan

blasted the bill as a bailout.

“It’s

outrageous that Exelon and ComEd are again requesting a bailout when

they are both profitable companies,” Madigan said. “This proposal would

force consumers to pay more only to boost the companies’ profits

further. The legislature has more important matters to address than

padding ComEd and Exelon’s profits.”

Nauman

bristles at opponents’ characterization of the bill as a bailout. He

says it’s really a recognition of the plants’ value to Illinois. As

pollution regulations tighten on carbon dioxide, coal plants across the

nation are expected to close, and Illinois is under a federal deadline

to reduce carbon dioxide emissions 33 percent by 2030. That means a loss

of electricity generating capacity, which could lead to higher energy

prices and even blackouts during times of peak demand. Nauman says

nuclear plants are the solution because they don’t produce carbon

dioxide and aren’t intermittent like wind and solar power.

Opponents

of nuclear power take issue with the industry’s “zero carbon” claim,

saying the large volume of concrete needed for plant construction and

the mining and refinement process for nuclear fuel both produce plenty

of carbon dioxide. Additionally, they say that there is always sun and

wind somewhere, so enough wind and solar installations could mitigate

intermittence.

David

Kolata, executive director of the quasi-governmental Illinois Citizens

Utility Board, opposes the current Exelon bill, but he says it could

work if it contained more consumer protections. He’d like to see a

“price ceiling” to protect customers from massive rate increases, as

well as more authority for the Illinois Commerce Commission and the

Illinois Power Agency to determine whether Exelon’s plan is fair to

consumers.

Kolata says

the Exelon bill should be combined with a separate “green jobs” bill

and another bill from power company ComEd to create a broader energy

package for Illinois. However, the hostile tone in the Illinois

Statehouse due to the current state budget crisis complicates any such

efforts.

“We see a

path here,” Kolata said. “This is an incredibly important issue. The

governor and legislative leaders know it’s important, too.”

An uncertain future

Besides

the potential ramifications for the state’s energy market, closing the

Clinton power plant would likely affect the economy in the surrounding

area and leave a cache of nuclear waste in central Illinois for millions

of years. The latter appears likely even if Clinton doesn’t close.

In

2015, Exelon paid nearly $13 million in property taxes on its Clinton

plant and the lake used to cool the plant’s reactor. The lion’s share of

that money – $8.4 million – went to Clinton Community Unit School

District 15. DeWitt County, which contains Clinton, received $2.2

million. Several other institutions also benefited from the plant’s

property tax revenue, including fire protection districts, libraries,

road districts, townships and community colleges in Decatur and

Champaign.

That revenue may not dry up instantly because decommissioning a

nuclear plant takes years; Exelon’s nuclear plant in Zion, Illinois,

closed in 1998 and isn’t expected to finish decommissioning until 2019

or 2020. Still, Nauman says the value of Exelon’s property is likely to

drop steeply because a defunct power plant is worth far less than a

functioning one.

Kraft

says nuclear power companies should be required to pay into a “just

transition” fund to help local governments ease off of revenue from

closing nuclear plants.

“The

time to plan for the end of the gravy train is not when your nose is

pushed up against the fan blade, but methodically, and in advance,”

Kraft said.

Clinton

Power Station employs about 700 people, and Nauman says Exelon has

offered each employee a position elsewhere in the company if the Clinton

plant closes. While those employees wouldn’t be unemployed, Nauman says

those which take other jobs within Exelon would likely have to relocate

out of central Illinois, creating an exodus of families which spend

money in the local economy.

Nuclear

power has been around since the 1970s, but governments and energy

companies have yet to reach a long-term plan for disposing of nuclear

waste beyond simply storing it. Depending on whom you ask, that’s either

a minor technical detail or a catastrophe waiting to happen.

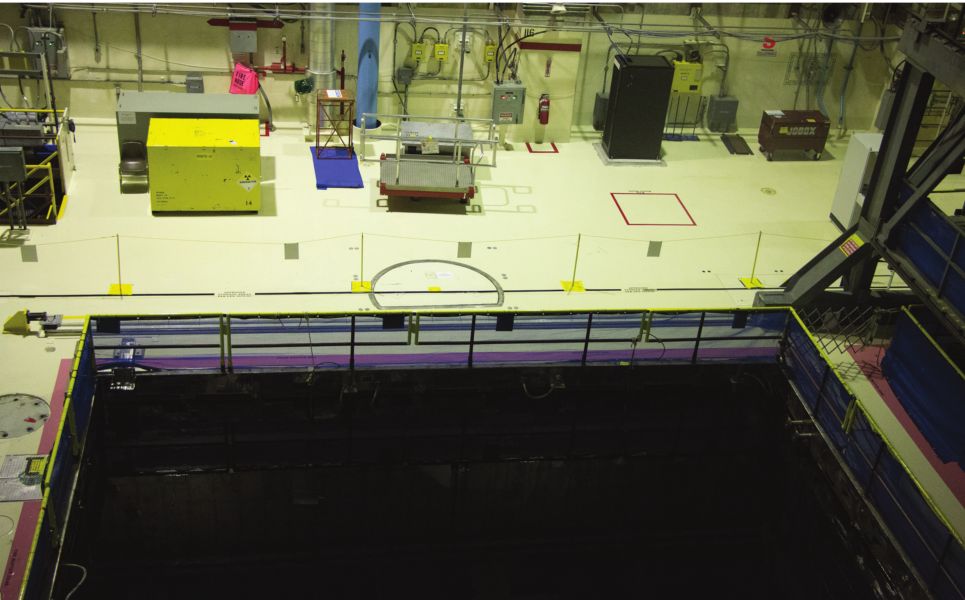

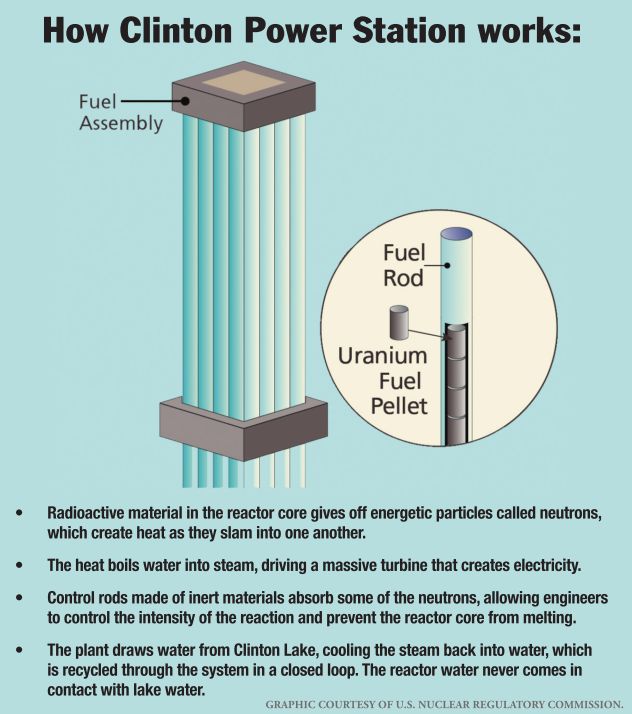

Spent

fuel rods are still highly radioactive, despite being too weak to

efficiently sustain a reaction. The spent rods are usually stored in a

temporary “spent fuel pool” filled with water to block radiation and

cool the rods from use. For long-term storage, they are placed in

on-site “dry cask” storage, which involves encasing the rods in a steel

canister filled with inert gas, then encasing the canister in thick

concrete. The casks, which usually sit behind barbed wire and armed

guards, are projected to last about 100 years, although environments

with corrosive elements like salt can drastically reduce the containers’

lifespan.

In theory,

spent nuclear fuel could be reprocessed and reused, but it’s usually

uneconomical to do so with the uranium used most frequently in nuclear

reactors.

Reprocessing plutonium, a lesser-used nuclear fuel, presents complications because it can be used for nuclear weapons.

Hannes

Alfven, a Nobel Laureate in physics who died in 1995, wrote critically

of nuclear power, saying that safe storage of its waste would require

unprecedented stability in human institutions and geologic formations.

Governments would have to last hundreds of thousands of years to keep

nuclear waste secure, he posited, and scientists can’t ensure that a

large earthquake or other event won’t destroy storage facilities.

“The

deposit must be absolutely reliable as the quantities of poison are

tremendous,” Alfven wrote in 1974. “It is very difficult to satisfy

these requirements for the simple reason that we have no practical

experience for such a long-term project.”

Additionally,

changes in language and understanding of symbols over long periods of

time may hamper efforts to warn future generations about the dangerous

material being stored.

All of the nuclear fuel

ever used in 29 years at the Clinton Power Plant sits in a pool roughly

50 feet square, situated inside the plant’s main building, with multiple

layers of security and monitoring. If the plant closes, the spent fuel

would likely remain on site even after the plant itself is dismantled.

In

2011, the federal government shelved plans for the Yucca Mountain

Nuclear Waste Repository, which would have been a site in the Nevada

desert devoted to storing the nation’s radioactive waste deep

underground. Officially, the project was canceled because of political

opposition, but the opponents cited safety issues and technical

questions they felt were unresolved.

While

the spent fuel from Clinton Power Station is likely to stay on site for

the foreseeable future, the lake built to cool the plant may not.

Exelon owns the land containing Clinton Lake, a popular site for

boating, fishing and camping managed by the Illinois Department of

Natural Resources. DNR could conceivably take over the lake, but the

agency would inherit the cost of maintaining the lake’s large dam at a

time when it has already undergone drastic budget cuts in recent years

that have affected its ability to maintain state parks and other

recreation areas.

As

Illinois lawmakers continue to spar over a possible budget deal several

days after the legislative session ended, Exelon’s window to reverse its

decision on Clinton and the Quad Cities is closing. The company has

already filed paperwork with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to start

the closure process, and the Illinois General Assembly would have to

approve the Exelon bill by September to give Exelon enough time to back

out.

“There is no

doubt in my mind that we are going to regret letting this plant and the

Quad Cities plant shut down in 2017 and 2018,” said Nauman. “I don’t

have high hopes that the legislature is going to do anything. If they

were going to, they would have already done it.”

Contact Patrick Yeagle at [email protected].