Abe’s files in peril

The world had always known about Grace Bedell, an 11-year-old girl who had urged Abraham Lincoln, months before he became president, to grow a beard, on the grounds that he would be more electable.

“All the ladies like whiskers and they would tease their husbands to vote for you and then you would be president,” the little girl wrote.

The letter has long been famous – Lincoln, who’d written back asking Bedell whether a beard might not be labeled “a piece of silly affectation,” stopped at the girl’s hometown en route from Springfield to the nation’s capital. Now whiskered, the president-elect called the girl out of the crowd for a face-to-face visit that included a kiss. There’s a statue in Bedell’s hometown of Westfield, New York, that commemorates the moment.

What wasn’t known, until 2007, is that Bedell wrote a second letter to Lincoln in 1864. It was never answered or acknowledged by the president – there’s no evidence that Lincoln ever saw it. Her family had fallen on hard times, Bedell explained in the letter written four years after the president had kissed her. Please, she asked, could I get a position with the Treasury Department?

Karen Needles, who found the letter at the national archives in Washington, D.C., while working for the Papers of Abraham Lincoln Project based in Springfield, says that she only has time to glance while looking through Lincoln records. Otherwise, she would never get anything done. But the very first lines of Bedell’s letter rang out.

“Do you remember before your election receiving a letter from a little girl residing at Westfield in Chautauqua Co. advising the wearing of whiskers as an improvement to your face?” Bedell began in her written plea for a job “I stand up in my chair, and I’m doing this jig,” Needles recalls.

It’s the sort of celebration that some scholars and lovers of the Papers of Abraham Lincoln Project fear might be less likely in the future.

Grants in jeopardy

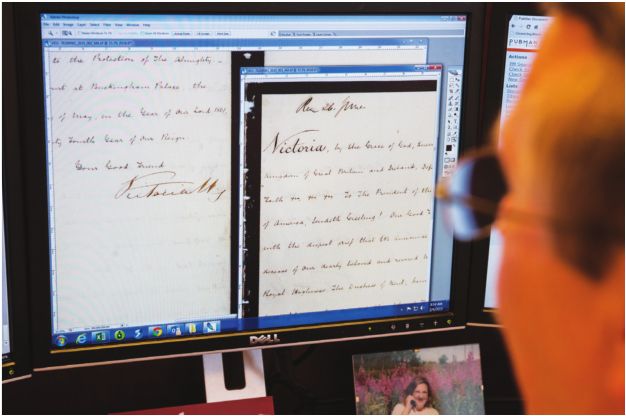

Turmoil has hit the papers project that is tracking down and digitizing every document ever written or read by the Great Emancipator.

An investigation by the office of the inspector general launched last fall has, so far, uncovered nothing. After being placed on administrative leave in April, Daniel Stowell, the project’s longtime director, was reinstated this week. The Illinois Historic Preservation Agency that employs Stowell refuses to say why he was placed on leave, even though the agency has previously released documents showing the basis for disciplinary action against an agency employee.

State funding has been slashed while the staff has been cut from a dozen to seven, with one of the five lost positions being in Washington, D.C., where Bedell’s second letter to Lincoln was discovered. The governor’s office has blamed the budget impasse. Meanwhile, grant money is being withheld due to questions about the project and its future.

The Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Foundation, a private organization that helped organize observances of Lincoln’s 200 th birthday in 2009, is withholding a $25,000 gift out of concern for the project’s prospects. The foundation’s gift is supposed to leverage additional money from the National Endowment for the Humanities, which last summer announced a $400,000 grant to the papers project, with $300,000 contingent on matching funds from private donors.

“We want a strong signal from the state that these investigations are going to be completed without any problems and leadership established on a permanent basis,” Harold Holzer, a Lincoln scholar who chairs the bicentennial foundation. “The foundation decided to just hold up on issuing the check until we were certain that the project would continue and the money would not simply go to pay debts or things like that…. Show us the money, right? Then we’ll show you ours.”

Holzer’s group isn’t alone in its concerns.

Last month, the National Historical Records and Publications Commission, which had provided annual grants of more than $96,800 in 2014 and 2015, postponed action on a grant application for this year. The commission could reconsider the application at its next meeting in November, says Keith Donohue, commission spokesman, who confirms that Stowell’s status prompted the commission to postpone action.

“There’s an issue with the project director, whether the project director will remain,” Donohue said. “Until the organization makes that decision, the commission decided to postpone the decision. We’re hoping we get an answer back from them before November.”

The project’s plummet from crown jewel to unfunded and under investigation is nothing short of stunning.

“This is the most important documentary project about Lincoln that exists,” says Matthew Pinsker, a history professor at Dickinson College in Pennsylvania. “I can’t think of anything more important for anyone who cares about Lincoln. … I’ve talked to many scholars. All of us seem worried. None of us know for sure what’s happening.”

The papers project, Holzer says, is vital. “As a historian, I’m very concerned that what promised to be the crucial and essential resource for Lincoln in the future is being threatened,” Holzer

says. “That all of this work and all of this fundraising is going to

fail to produce the product that everybody had expected. … It would be a

disaster if the material wasn’t produced and posted as promised.”

Chris

Wills, IHPA spokesman, said that Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library

Foundation has raised $100,000 to use as matching funds for federal

grants and that the governor is “committed” to funding the program. A

plan to publish documents that have not yet been put online should be

finished within weeks, he wrote in an emailed response to questions from

Illinois Times.

“The importance of the

Papers of Abraham Lincoln is clear to everyone,” Wills wrote. “Decisions

about the project’s operations have always been based on how to best

use taxpayers’ money to achieve the project’s goals.”

Grants and praise

Formed

in 1985 under the administration of Gov. Jim Thompson, and before the

internet existed, the papers project, now headquartered at the Abraham

Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, began as an attempt to compile

every legal document Lincoln wrote or read during his career as a

lawyer. It seemed a monumental challenge.

Archival

records from Lincoln’s lawyering days had been destroyed in the Great

Chicago Fire. Thieves had scavenged courthouses, swiping untold numbers

of documents.

William Herndon, Lincoln’s

former law partner, had given documents away as gifts. There was a

widespread assumption that undiscovered documents either didn’t exist,

could never be found or were of no consequence, writes Allen C. Guelzo, a

history professor at Gettysburg College in Pennsylania, in a review of a

1,434-page, four-volume collection of transcribed Lincoln legal papers

published in 2008 by the papers project.

“The

singular achievement of the ‘Lincoln legals’ (papers project) was its

refusal to accept the prevailing judgment that little of Lincoln’s legal

paperwork had survived, or if it had, that it would tell no interesting

tales,” Guelzo wrote eight years ago.

Thanks

in part to the project, enough light has been shed on Lincoln’s legal

career to know that he was a workaday attorney, mainly concerned with

civil matters, who largely handled cases having to do with property,

debt collection and railroads. Combing courthouses, the project’s

employees compiled 96,000 documents that included records from 5,600

cases. They found such treasures as documents from an 1855 defamation

case in which Lincoln represented a DeWitt County client who had sued a

brother-in-law on the grounds that he was not, contrary to his

relative’s claim, a Negro. Lincoln won. The case is infamous for Lincoln

extending his arm in the direction of the table where defense attorney

C.H. Moore sat, watching, while Lincoln denied that the plaintiff, a man

who claimed Portuguese descent, was black.

“I say my client may be a Moor, but he is not a Negro,” Lincoln intoned.

In

2000, when Stowell took over, researchers set sights even higher,

deciding to collect every document that Lincoln had ever written or read

and put it all online, and so the Lincoln Legal Papers Project dropped

“legal” from its name and cast its net beyond courthouses, finding such

treasures as the Bedell letter and a report from the first doctor to

treat the stricken president at Ford’s Theater, obviously not something

that Lincoln had written or read, but worthwhile nonetheless.

The

project spent years identifying likely repositories before researchers

hit the road in 2005, combing the nation for Lincoln documents.

“We

would travel for two weeks at a time, and we would hit all the

repositories,” recalls John Lupton, former associate director for the

project who now works as executive director for the Illinois Supreme

Court Historic Preservation Commission. “We would ask, ‘Do you know of

anyone in the area who might have a Lincoln document?’ We ended up

finding a lot just by asking people on the ground.”

Stowell’s

outfit seemed a bright spot amid a storm of dysfunction at the

presidential library and museum, where the museum’s director in recent

years was locked in a power struggle with the director of IHPA, which

oversees the institution where five directors, both permanent

and interim, have worked since opening day in 2005. A sixth is scheduled

to start work this summer. While attendance, funding and staffing at

the museum and library fell off over the years, the papers project,

thanks largely to grants, enjoyed a stable staff and budget. Last

August, the papers project was lauded by politicians when the National

Endowment for the Humanities announced the $400,000 grant, substantially

larger than previous NEH grants of $200,000 and $250,000.

“The

Papers of Abraham Lincoln has played an integral role in providing

Illinois visitors and residents alike the opportunity to experience the

magic of Lincoln’s legacy,” U.S. Sen. Dick Durbin said at the time.

Less than a month later, the papers project was under investigation and in crisis. Its supporters say they can’t understand why.

“I study complicated things, and this is too complicated for me to figure out,” Pinsker says.

Kathryn

Harris, retired director of the presidential library who is now

president of the Abraham Lincoln Association, says that she has no

answers.

“I’m not sure what’s broken, and I don’t know who decided it was broken,” Harris says.

“It was crazy”

As

much as anything, the spiral of the papers project is a story of palace

intrigue rooted in a power struggle between former ALPLM director

Eileen Mackevich, who resigned last fall, and former IHPA director Amy

Martin, who was terminated by the agency’s board one month after

Mackevich’s resignation.

Created

the same year that IHPA was formed, the papers project is somewhat a

standalone, a partnership between IHPA, which provides space at ALPLM

and the director’s salary, the University of Illinois Springfield that

supplies researchers and the Abraham Lincoln Association, a private

group that provides financial support.

According

to Mackevich, Martin and Nadine O’Leary, then chief of staff and now

interim director of ALPLM, wanted more authority over the papers

project. Martin could not be reached for comment. O’Leary declined an

interview request.

“Stowell

had a system predating Amy’s arrival where the people who were on the

staff of the papers were actually employees of UIS,” Mackevich says.

“That irritated Amy and Nadine up the kazoo because they weren’t their

employees.”

Stowell, according to Mackevich, may have had another strike against him.

“They

viewed him as my crony,” said Mackevich, who was clashing, sometimes

openly, with Martin over who had authority to make decisions at the

presidential library and museum. “Stowell was a major part of what I

thought was important in the library’s work.”

Last

September, less than three weeks after the National Endowment for the

Humanities announced the $400,000 federal grant, Stowell met with

Martin. Mackevich was in the room.

“It

was crazy,” Mackevich says. “First, she announced that Stowell can no

longer report to me and I’m no longer in charge of anything as far as

the papers.”

Mackevich recalls that Martin said that there was a concern about money being misused.

“And

I said to her at the time: ‘What kind of misuse of funds? I have read

all of the expenditures. They are turned in to me before they are turned

in to you, Amy, and I saw no misuse of funds,’” Mackevich recollects.

“’If you don’t like the way we’re doing it, I understand there’s new

rules and a new governor. We can change the system to conform.’” But

Martin stood firm, according to Mackevich and a memo Stowell wrote and

gave to backers of the project. The project’s funds were frozen, the

inspector general was launching an investigation, the state would not

renew a contract with UIS to provide researchers and Stowell was not to

apply for grants or speak with the media, Martin told Stowell, according

to the memo. There was, Stowell wrote in his

memo, a concern that the papers project had been spending money without

Martin’s authorization or knowledge.

“There

never has been and is not now any intention to hide any expenditure,”

Stowell wrote in his memo. “I welcome an Office of the Inspector General

examination of our expenditures, but as that process takes place, all

of my colleagues will lose their jobs.”

The

memo reverberated, with project supporters worrying that this was an

existential crisis. There were mixed signals from IHPA, which first said

last fall that the state would not apply for a National Historical

Records and Publications Commission grant, then reversed itself, saying

that the state would, in fact, seek the federal grant that’s now in

limbo due to concerns about Stowell’s status. The governor’s office

refused to renew a contract with UIS to provide researchers for the

project, prompting layoffs. Joseph Beyer, a top adviser to Gov. Bruce

Rauner, told an ALPLM advisory board that the governor couldn’t renew

the $243,000 contract because the General Assembly hadn’t approved a

balanced budget.

Wills

now says that the papers project, rather than continue as a unit of

IHPA, is being made part of the ALPLM, which is under the historic

preservation agency. The move, Wills wrote in his response to questions,

reflects a desire to “remove any communications barriers” as well as

provide the project with financial and administrative support.

That Stowell could have engaged in misconduct that merited an inspector general’s probe stuns the project’s supporters.

“Daniel

Stowell has a great reputation,” Pinsker says. “Scholars respect him

enormously. He’s done an incredible job of leading the project. Like

many people, I’m worried that he’s become a victim of bureaucratic

politics and the budget crunch.”

Harris is skeptical that Stowell has done anything wrong.

“Hell

no, and you can quote me on that,” Harris said. “My gut, my heart,

tells me no. Daniel’s character is not of that nature, the Daniel that I

know, and I’ve known Daniel since he started at the project. … Daniel

wrote grants to God and the world to get money to keep the program going

because state funding was not adequate to continue the staff that he

had.”

Regardless of

whether there had been any impropriety, damage had been done. Woes

surrounding the papers project hit national radar this spring via a

critical story, then editorial, in the New York Times.

“Someone

– Gov. Bruce Rauner, perhaps – had better cut through the mess soon

enough to guarantee the continued operation of the long-running,

nationally respected project before Illinois becomes the Land of Lost

Lincolnia,” the Times editorial board intoned in March. “(T)he

state’s political leaders should summon their inner Lincoln and find

ways to fully restore the project as a continuing lesson on the nation’s

ever fractious political history.”

Part

of healing and restoring the project’s finances is removing any whiff

of scandal, Mackevich says. Donors don’t want to hear about

investigations and directors being placed on paid leave, she said.

“I

think that in the world of grants and in the world of competition for

grants, people want to have as squeaky-clean a record as they can,”

Mackevich said. “Even though this was a great academic project of the

library, the fact that there are so many questions at this point will

arouse people’s suspicions.”

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].