Illinois Innocence Project marks 15 years

Teshome Campbell doesn’t hold any grudges. Not against the public defender who failed to call crucial witnesses on his behalf. Not against the many judges who dismissed his claims of injustice. Not even against the people who lied about him in court and caused him to spend 18 years behind bars for a crime he always insisted he didn’t commit.

“I told myself three things: I’m not going to try to make up for lost time, I’m not going to keep up with the Joneses and the Kardashians, and nobody owes me anything,” Campbell said. “I came out of there with no grudges. I forgave everybody everything – even the guys who lied on me, people who done me wrong. I don’t blame them for nothing.”

Campbell is the latest person freed from prison by the Illinois Innocence Project at the University of Illinois Springfield. In all, the group has earned freedom for nine people since its inception in 2001. The Illinois Innocence Project celebrates its 15 th anniversary this month as part of a nationwide network of such groups focused on overturning the wrongful convictions of people falsely imprisoned.

Convicted on a lie

In the early hours of Christmas morning in 1997, while it was still dark out, James Shepherd and sex worker Rita Butler bought what they thought was crack cocaine from some men on East Bellefontaine Street in Champaign’s north end. When they discovered the supposed drugs were fake, Shepherd returned to demand his money back. The men kicked, punched and stomped him till he was unconscious, and the police found him lying in the street in a pool of blood. News reports from the time say his brain was severely damaged, and he died in the hospital about a month later.

Teshome Campbell, then 21 years old, was one of several people arrested in connection with the homicide. Butler told police that she saw Campbell start the fight while she sat inside a van facing the opposite direction and parked around the corner. Campbell, who lived several blocks away, denied being involved and told the police that at the time of the beating he was visiting someone who lived at the scene of the crime.

Ultimately, Campbell and several other people faced individual criminal trials for Shepherd’s killing. Two of the men who were originally charged with murder received immunity in return for testifying against Campbell. Both men had criminal histories which involved fighting. Campbell’s public defender didn’t call any of the witnesses who would have testified on his behalf, and despite no physical evidence tying him to the crime, Campbell was convicted in 1998 and sentenced to 55 years in prison.

Campbell never stopped asserting his innocence. The News-Gazette in Champaign- Urbana reported that after his conviction, Campbell said, “It’s not over,” to his family as he was led out of the courtroom. While in prison, Campbell began learning about the legal system, and he filed several pro se pleadings over the following years, asking again and again for his case to be reheard. The Illinois Supreme Court declined to take Campbell’s case at least three times, but even that didn’t stop him.

Campbell raised several claims regarding his trial. He protested that his Fifth Amendment right to remain silent should not have been allowed in court as evidence of guilt. He challenged the admission of “hearsay” statements as evidence. He raised questions about the photo lineup method that the police used to identify him as a suspect. The list of claims Campbell raised is extensive, but court after court found reasons to dismiss his pleas.

In 2008, Campbell asked the U.S. District Court in Urbana to look at his case, but the federal court decided to wait until another appeal in the state court system had run its course. When the state appeal failed in 2009, it exhausted Campbell’s chances there and made the federal court his last hope. U.S. District Judge Harold Baker in Urbana originally dismissed Campbell’s case.

The Illinois Innocence Project began investigating Campbell’s case in 2012. Former IIP attorney Erica Nichols Cook, who now works in

the Illinois Office of the State Appellate Defender, headed the

investigation. She and her team tracked down the witnesses who would

have testified for Campbell during his trial, submitting affidavits from

those witnesses to the court and preparing a clemency petition for the

Illinois Prisoner Review Board.

Eventually,

Baker appointed Truscenialyn Brooks and David Pekarek Krohn, two

associate attorneys with the Madison, Wisconsin, office of international

law firm Perkins Coie, to represent Campbell in federal court. Their pro bono work,

combined with the investigations conducted by the Illinois Innocence

Project, helped convince the U.S. Court of Appeals of a claim Campbell

had been making for years: that his public defender made a serious error

at trial by not calling witnesses who would have testified that

Campbell wasn’t involved in the homicide.

"It is impossible to describe what it means to be able to help give someone a piece of their life back...”

-Larry Golden

The appellate court

sent the case back to Baker, who held an “evidentiary hearing” in

October 2015 to examine the evidence that Campbell had long asserted

should have been used in his trial to clear him. At that hearing,

Campbell’s public defender, Urbana attorney Harvey Welch, explained that

he chose 18 years ago not to call any of the witnesses who would have

testified on Campbell’s behalf because his trial strategy was predicated

on the crime scene being too dark for anyone to see.

“…I

came to the conclusion early on that it would not necessarily be

helpful to bring witnesses on Mr. Campbell’s behalf and somehow argue

that these witnesses could see what was going on but that the state’s

witnesses couldn’t,” he said.

Baker ultimately vacated Campbell’s conviction on Dec. 30, 2015 – 18 years and five days after the murder of James Shepherd.

“It

was thrilling. We were over the moon,” Pekarek Krohn said. “Although

this was not technically a case where we had to show actual innocence,

we have believed in his innocence since the day we met him.”

Nichols Cook says Campbell’s case highlights problems in the justice system.

“The most poignant part of Teshome’s story is how the Illinois courts failed him,” she said.

In

January, Champaign County State’s Attorney Julia Rietz decided not to

retry Campbell. Although she maintained that the original conviction was

appropriate given the evidence at Campbell’s trial, Rietz said in court

papers that it would be impossible to adequately prosecute the case

again, “in light of evidentiary issues that have arisen during the

passage of time.”

Campbell,

now 39, was released from Danville Correctional Center on Jan. 29.

Within 10 days, he had secured a full-time job, and he recently took on a

second job.

“I had to

fight; I didn’t want my character assassinated,” he said. “I knew what

type of person I was. I knew I didn’t do this, and I didn’t want to

plead guilty to something I didn’t do. That wouldn’t be right. That’s

one of the reasons I could come out smiling.”

One of the men who received immunity for testifying against Campbell was later convicted of a different murder.

Campbell’s

case is part of a growing trend of exonerations nationwide. The

National Registry of Exonerations maintained by the University of

Michigan Law School shows that the rate of exonerations has increased

substantially each decade since 1989. In the 10 years spanning 1989 to

1998, there were 360 exonerations across the U.S., for an average of 36

exonerations each year. From 1999 to 2008, there were 671 exonerations

for an average of 67 each year. In the seven years from 2009 to 2015,

there have already been 715 exonerations, for an average of 102 each

year. In the first three months of 2016, there were at least 26

exonerations across the U.S.

In

Illinois, there have been at least 169 exonerations since 1989,

according to the database. In the 10 years spanning 1989 to 1998,

Illinois saw 37 exonerations for an average of about four per year. From

1999 to 2008, there were 65 exonerations in Illinois – an average of

about seven per year. In the seven years spanning 2009 through 2015,

there were 61 exonerations, with an average of about eight per year. So

far this year, Illinois has seen at least six exonerations, a rate that

could yield as many as 18 exonerations in 2016.

The

quickening pace of exonerations is due to several factors like

advancements in DNA and other scientific investigation techniques,

continued efforts of innocence projects and an overall attitude shift in

the criminal justice system toward acknowledging that wrongful

convictions do occur.

When

the Illinois Innocence Project started in 2001 as the Downstate

Innocence Project, such programs were a relatively new idea. Attorneys

Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld created the original Innocence Project in

1992 at Yeshiva University’s Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law in New

York. It was Scheck’s 2001 call to arms which inspired Larry Golden,

Springfield private investigator Bill Clutter and former UIS professor

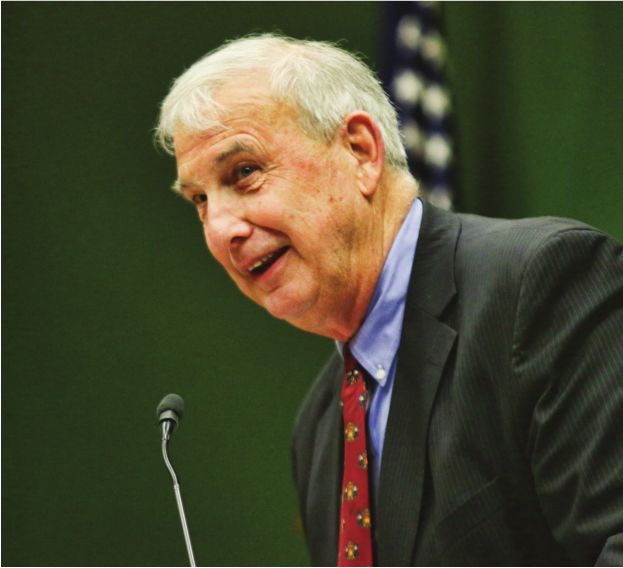

Nancy Ford to start the Downstate Innocence Project. Golden still serves

as founding director of the Illinois Innocence Project, a name the

group took in 2012 to reflect its statewide expansion and partnership with Illinois’ three public law schools.

What

started as a handful of Legal Studies students at UIS has grown to

include attorneys on staff and a team of volunteers. The group has

helped gain freedom for nine people who served a combined 165 years of

prison time for crimes they didn’t commit. IIP only takes on cases in

which the defendant is believed to be actually innocent, and its cases

typically deal with serious crimes like murder. Currently, IIP has 26

active cases, but it receives hundreds of requests for help each year.

In

late 2015, IIP announced a program aimed at helping Latino inmates who

don’t speak English. Aided by a federal grant, the program involves

hiring two additional Spanish-speaking staff attorneys, translating its

intake forms and other paperwork into Spanish and examining cases

involving Latino inmates for possible DNA evidence.

Before

2015, individuals who pleaded guilty were not allowed to later ask for

DNA testing in their cases. Illinois lawmakers changed that last year.

Golden says between 90 and 95 percent of criminal cases result in a

guilty plea, so the possibility to challenge convictions with DNA

evidence after a guilty plea opens up numerous cases to reexamination.

“We believe this is a huge area of possible wrongful convictions,” he said.

Although

much of IIP’s work is funded by federal grants, each grant brings

additional expenses and specific limits on how the money can be used.

Golden says such grants don’t cover administrative expenses and general

overhead, so the group must constantly raise money just to use the

grants.

“The more

federal grant money we receive, the more work and oversight we take

responsibility for without funding within the grant to cover that,” he

said.

Golden says his

work with the Illinois Innocence Project is the most rewarding – and

frustrating – thing he has ever done. It involves reforming what he

calls “one of the most major uses of power in American society,” and the

students who work with the group take lessons from that experience into

their careers.

“It is

impossible to describe what it means to be able to help give someone a

piece of their life back as we walk innocent people out of prison who

have been there for 10, 20 or even 30 years for crimes they did not

commit,” he said. “Some of these individuals become part of our

‘family,’ but most importantly we know that we have participated in

their achieving some freedom and hopefully some opportunity in their

lives.”

Teshome Campbell says he never would have gotten out of prison without help from the Illinois Innocence Project.

“I feel like if heaven was missing any angels,” he said, “I know where we could find some.”

The

Illinois Innocence Project will celebrate its 15 th anniversary at the

Ninth Annual Defenders of the Innocent Event on April 30 at the

President Abraham Lincoln Hotel in Springfield. Kirk Bloodsworth, the

first death row inmate exonerated by DNA in the U.S., is the featured

speaker. For more information, call 206-6569 or visit uis.edu/

illinoisinnocenceproject.

Contact Patrick Yeagle at [email protected].