Ex-pols’ campaign funds are gifts that keep giving

Nearly 20 years ago, former Gov. Pat Quinn looked like a proverbial pauper.

Quinn had less than $150 in his campaign war chest as of June 30, 1998, a seminal moment for campaign funds in Illinois. As part of a campaign-finance reform bill passed by the legislature that year, money collected after that date could not be spent for personal use. Money already in the bank could be spent on virtually anything, so long as pols paid income taxes for money spent on themselves. While some elected officials had six or even seven figures in the kitty, Quinn was nearly broke.

The legislature’s reform move was forced by Management Services of Illinois, a Springfield company that had showered Gov. Jim Edgar and other public officials with campaign contributions and gifts while landing a lucrative contract with the state Department of Public Aid. Taxpayers were bilked out of $7 million paid to MSI for work that wasn’t done, federal prosecutors charged. A co-owner of MSI was convicted on corruption charges, as was the company itself, plus a top Department of Public Aid administrator.

The message seemed clear. “Given the developments over the last several months at the MSI trial…it seems to me that actions should be taken to eliminate the gravy train in Springfield,” House Speaker Michael Madigan said after the trial.

And so the speaker proposed reforms that included limits on the size of campaign contributions, beefed-up disclosure requirements, a ban on spending campaign cash for personal use and a sunset clause that would require former elected officials to shut down campaign funds within one year of leaving office.

It was not an easy sell in the General Assembly, where lawmakers had grown accustomed to anything goes. Once money was received, it could be used for virtually anything, and elected officials could, and did, use campaign accounts to buy cars, pay babysitters to watch their kids and provide nursing home care for loved ones. The family of one deceased lawmaker used campaign money to pay for his funeral.

What eventually passed was watered down considerably from what Madigan had said that he wanted. Gone was the proposed requirement that campaign funds be shut down when elected officials became private citizens. Lawmakers also refused to approve a blanket ban on spending campaign money for personal use. Instead, the new law allowed lawmakers to use campaign money they had on hand as of June 30, 1998, for anything they liked, and they could take as long as they liked to do it. Money collected after that date could be spent only on charitable, governmental or political purposes, or it could be returned to donors, but it could not be siphoned for personal use.

The reform measure should, ostensibly, have made Quinn a proverbial pauper, given than he had just $149.53 in his campaign fund on June 30, 1998. But when it comes to campaign finance law in Illinois, there’s often a way so long as there is a will, and Quinn’s campaign disclosure reports documenting expenditures since he’s left office prove it.

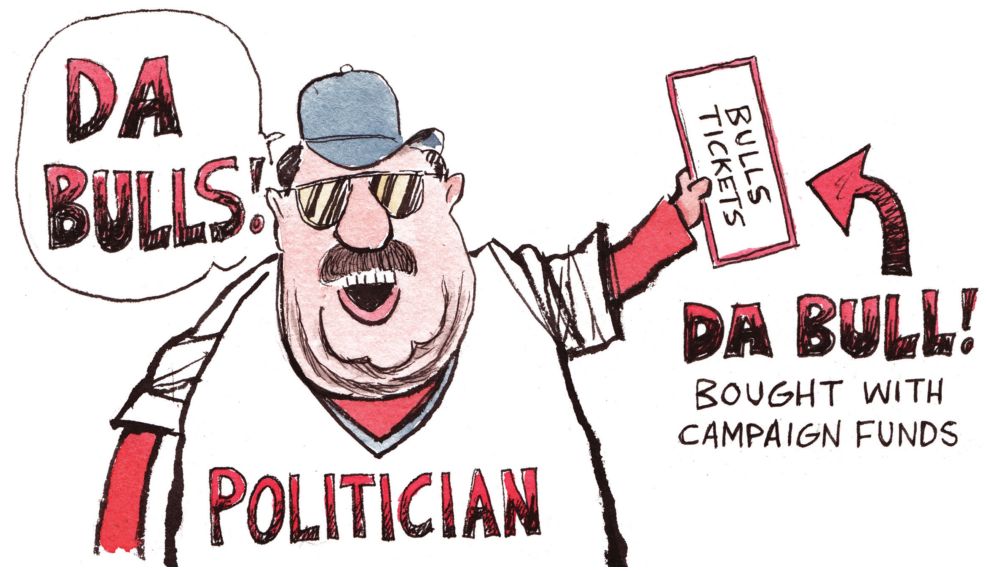

Stays at hotels in New York, San Francisco and Washington, D.C.? Check. Subscriptions to the New York Times and Chicago Sun- Times? Check. Internet and cable television service? Check, again. Want to see a Chicago White Sox game? Call Quinn – he might be able to help, given that his disclosure reports show that he spent $1,550 for tickets last October and December, plus $2,700 for tickets in January of 2015, plus $350 for Chicago Bulls tickets in February of last year. Reports also show that Taxpayers for Quinn has an employee who makes $2,332 per month and an office in Chicago that cost the committee more than $8,882 in rent during the fourth quarter of last year. The committee spent $4,291 on airfare last year. Reports aren’t clear on destinations or the purposes for trips taken after Quinn became a private citizen. There are also plenty of restaurant tabs, contributions to politicians and donations to charity.

All told, Quinn spent $287,635 from his campaign fund last year, when he was neither governor nor a candidate for any elective office, and he had $424,655 left as of Dec.

31. And Quinn, who could not be reached for comment, isn’t unique.

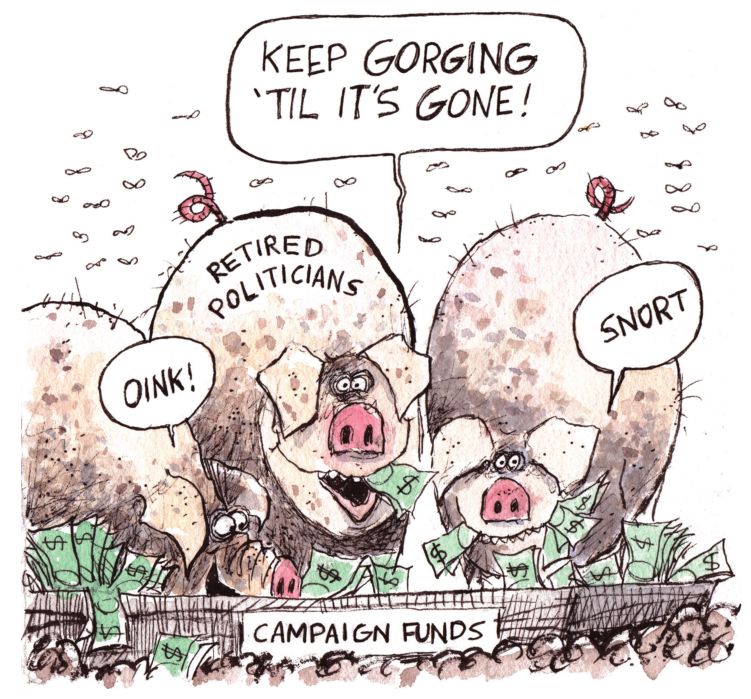

Campaign

disclosure reports show that retired politicians in Illinois use

leftover campaign cash for hotels, airfare, gifts, meals, tickets to

sporting events and direct payments to themselves. It can take more than

a decade for former officeholders to deplete their campaign funds – for

example, former Gov. Edgar, who left office in 1999 and announced six

years later that he would never again be a candidate for office, still

has more than $400,000 in his campaign fund. In some cases, retired

politicians have received campaign contributions even after they’ve left

office.

While

campaign funds can legally exist in perpetuity in Illinois, critics say

that it isn’t ideal for a state known more for political gridlock and

corruption than good government.

“I

guess, in a perfect world, you would want the campaign funds to close,

if, in fact, the person isn’t going to be running for office,” says

Susan Garrett, chairwoman of the board of Illinois Campaign for

Political Reform, a nonprofit group aimed at fighting corruption and

instilling transparency in politics. “The state has become much stricter

on how those dollars can and cannot be used – the good thing is, the

state is moving in the right direction. On the other hand, I believe

that campaign accounts should be terminated within a year or 18 months

after a lawmaker leaves office. That would be the right thing to do.”

Then

again, Garrett is a former state senator whose campaign fund is still

open three years after her replacement was sworn in. Disclosure reports

show that she has donated to political candidates and causes and also

spent campaign cash for such expenses as license plate renewal and a

subscription to Capitol Fax, a blog devoted to state politics. She had

more than $30,300 in her fund when she left elected office in 2013 and

had nearly $4,600 left as of Jan. 1, less than the $20,800 the fund owes

to her and her husband for loans they made to her campaign in 1998.

Why not pay back the loans and close out the campaign account?

“I

left my account open primarily to give to other candidates,” Garrett

answers. “I didn’t have a lot of money to begin with. … To me, the

money’s been set aside. We (myself and my husband) made that decision

that the dollars should be used to support other like-minded

candidates.”

Ex- governors keep funds

going At least four states require politicians to shut down campaign

funds once they are no longer candidates or elected officeholders. In

Maine, for example, politicians must close out campaign accounts within

four years of leaving office or losing their last election.

By

contrast, former Gov. Jim Thompson didn’t zero out his campaign fund

until 2004, more than a dozen years after he left office in 1991. Along

the way, disclosure reports show that he got at least one contribution, a

$1,000 gift from a Moline restaurant owner in 2000. The reason why

isn’t made clear in disclosure reports.

Edgar’s

campaign fund has lasted longer than his tenure as governor. He had

more than $2.8 million in his campaign account as of June 30, 1998, when

state law changed so that money collected after that date could be

spent only for governmental or political purposes, as opposed to

personal use. Since announcing that he wouldn’t run for reelection,

Edgar’s biggest expenditure, by far, has been a $1 million donation to

Ronald McDonald House Charities on Dec. 31, 1998, shortly before his

successor, George Ryan, was sworn in and was welcomed to the governor’s

office by his predecessor with $439 in gifts, paid for with campaign

money, from Cigar Czar, a company in Kankakee, Ryan’s hometown.

Like

other Illinois politicians (“Lifestyles of the Rich and Elected,” March

17, 2016), Edgar hasn’t been tight with campaign money. For example, in

1998, before leaving office, Edgar spent nearly $1,600 from campaign

funds to send Claudia Cellini, daughter of political powerbroker William

Cellini, on a trip that included stops in Hong Kong and Nepal. There

were also tabs for hotels and meals in India and Singapore around the

same time, although who slept and ate on Edgar’s campaign dime isn’t

made clear from campaign disclosure reports. In 2011, William Cellini

was convicted of federal corruption charges related to his dealings with

the administration of former Gov. Rod Blagojevich and sentenced to a

year in prison.

Since

leaving office, Edgar has spent tens of thousands of dollars on airfare,

hotels and other travel expenses. He has also donated to such

institutions as the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, the

Ronald Reagan Society, the Salvation Army, the Vermilion County Animal

Shelter and Laurel United Methodist Church in Springfield. Several

times, he has purchased flowers (for what occasions aren’t made clear

from reports) from his campaign fund and reimbursed himself for mileage.

The

tab for a security fence, its location not made clear in disclosure

reports, came to more than $66,000 in 1999, after Edgar became a private

citizen. That same year, Edgar paid more than $1,200 to Hart, Schaffner

and Marx, a Chicago clothing manufacturer, for jackets. Edgar has

billed his campaign for thousands of dollars in gifts, with items

purchased from Tiffany and Co., Marshall Field’s, Famous Barr and

Springfield Clock, among others. He has also given to several political

candidates and causes. In 2014, Edgar helped the failed gubernatorial

campaign of Kirk Dillard, a former staffer who went on to become a state

senator, with $25,000 coming as an outright contribution and an

additional $50,000 given as a loan that was repaid in the fall of 2014.

On Election Day that year, Edgar’s campaign paid more than $340 to

Stretch Limousine, Inc., for transportation. Edgar’s Federal Express

bill topped $7,400 in the third quarter of 2012. It is not clear from

reports what he shipped or to whom. The FedEx bill came seven years

after Edgar vowed that he would never again be a candidate.

“Today

I say never – this is it,” Edgar said during a tearful 2005 press

conference. “I truly mean it. This is my last political press

conference.”

Edgar

could not be reached to discuss spending from his campaign account since

he left the governor’s office, nor could several other former

politicians whose campaign funds remain active years after they left

office.

Sports tickets and consulting fees Not all politicians keep their campaign accounts open.

Former

state Rep. Rich Brauer, R-Petersburg, closed out his campaign account

in the spring of last year, shortly after he left the General Assembly

to take a top administrative post in the Illinois Department of

Transportation. His last hurrah was a $1,457 contribution to St. Jude

Children’s Hospital in Tennessee, which brought his campaign fund’s

balance to zero.

“I just thought it was the thing to do,” Brauer said of his decision to close his campaign account. “I didn’t need it.”

Some

ex-politicians, apparently, do need the money, or at least think so.

For example, former Sen. Larry Bomke, R-Springfield, who didn’t run for

reelection in 2012, still had more than $417,000 in his campaign fund as

of Jan. 1, according to disclosure reports. Bomke was never seriously

challenged at the polls after winning his first election to the state

Senate by 51 percent in 1996. He won by nearly 73 percent two years

later, when the General Assembly established June 30, 1998, as the

cutoff date – candidates could pocket funds collected prior to that

point, so long as they paid income taxes, but could not spend any money

collected afterward for personal use. Bomke then had more than $121,000

in his campaign account.

Disclosure

reports show that Bomke has been slow to spend money that piled up even

when the senator was a lock to win reelection. Bomke had more than

$472,000 in his campaign fund when he left office in 2013; as of Dec.

31, he had disposed of less than $55,000, mostly via contributions to

charity, GOP political committees and Republican candidates.

Bomke

could pocket more than $121,000, the amount he had on hand when the law

on personal use of campaign funds changed in 1998. He said he has no

plans to do that, nor does he have any plans to close out his campaign

fund anytime soon.

“My

wife and I will continue to distribute the money to political

candidates and community organizations in trying to be as helpful as we

can with those organizations,” Bomke said. “We’re not going to spend it

all at once.”

Former

state Rep. Raymond Poe, R-Springfield, had nearly $100,500 in his

campaign account as of Jan. 1. He had more than $45,000 on hand as of

June 30, 1998, and so can spend that amount however he likes so long as

he pays income taxes if the expenditure is for something personal.

Appointed last fall to head the state Department of Agriculture, Poe

could not be reached to discuss what he might do with his campaign money

now that he is no longer a candidate for office.

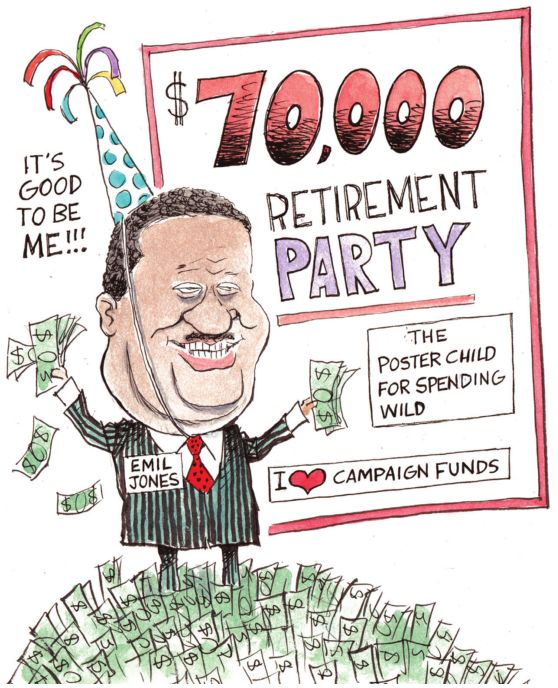

And

then there is Emil Jones, Jr., former president of the Illinois Senate,

and, arguably, the poster child for anything-goes campaign spending

once politicians leave office.

Jones

established his campaign fund in 1974 and had a balance of more than

$577,600 as of June 30, 1998, the date when politicians were no longer

allowed to spend campaign money for personal use. Jones had more than

$1.2 million in 2009, when he left office.

Jones’

disclosure reports show that the catering bill for his retirement party

at the Hyatt Regency Hotel in Chicago totaled more than $70,000 in the

spring of 2009, when he was no longer a senator. The hotel, however,

gave back more than $2,500 in overcharges, according to reports.

The tab for Jones’ going-away party was the least of it, disclosure reports show.

Since

2009, Jones has spent more than $104,800 on Chicago Bulls tickets,

according to disclosure reports. During that same time period, he has

also loaned himself $58,000 and paid back $20,000. He has also loaned

Emil Jones III, his son who took over his Senate seat, at least $13,300,

according to reports that show an additional $13,400 in loans to “Emil

Jones,” without making clear whether the money went to the younger or

elder Jones. All told, the campaign since 2009 has loaned at least

$84,700 to either the elder or younger Jones, with $27,700 of those

loans outstanding as of Jan. 1. Neither a telephone call nor an email

query to Sen. Emil Jones III, D-Chicago, was returned.

The

former senator last year paid himself $40,000 from his campaign fund

for consulting, although two consulting firms he established after

leaving the Senate had been dissolved by the secretary of state in 2010

and 2014 for failure to file required annual reports. Jones also paid

himself $3,500 last year from his campaign fund for “field work.” In

2014, Jones collected $100,000 from his campaign fund for “political

work.”

The

retired senator has a zest for travel, judging from disclosure reports

showing that his campaign fund since 2009 has spent more than $20,200

for airfare and hotels involving such destinations as Washington, D.C.,

North Carolina, Florida and Puerto Rico. He also appreciates fine meals

and socializing, given that disclosure reports show that campaign money

has been spent for dues and meals at the Sangamo Club in Springfield as

well as membership dues for social organizations in Chicago.

There

have been a smattering of contributions to the erstwhile senator, with

Hewlett Packard donating $4,000 to Jones’ campaign fund in 2011, two

years after he left office. The 3M Corporation gave $500 in 2013, the

AKA Foundation of Chicago gave $250 that same year and the political

action committee for Township Officials of Illinois gave $400 in 2012.

His son, the sitting senator, contributed $5,000 in 2010. But the

biggest contributor to Jones’ campaign fund since the senator retired

has been Jones himself.

Records

show that Jones has given $61,000 to his own campaign fund since

leaving office. It’s not clear why. State law bars individuals from

contributing more than $5,400 to a candidate, but committees can

contribute considerably more, and so it is possible that Jones used his

committee to make contributions larger than he could have made as an

individual.

Politicians

can use campaign cash collected prior to June 30, 1998, for anything so

long as income taxes are paid on expenditures deemed personal.

Jones’

disclosure reports show that he’s paid $13,480 in taxes to the state

and to the federal government from his campaign fund since leaving the

Senate in 2009. It’s impossible to say from public records whether Jones

has paid additional taxes from other sources.

Slightly

less than half of the more than $1.2 million Jones had in his fund when

he left the Senate had been collected prior to the law changing in

1998, so he can use it for anything. The other half can be used for

expenses incurred in carrying out governmental duties or performing

public service, but not for personal things. Former Gov. Quinn, who

received a $100,000 contribution from Jones’ campaign fund in 2010,

$25,000 in contributions in 2013, a $50,000 contribution in 2014 plus

$250,000 in loans in 2014, appointed Jones to head the state Sports

Facility Authority in 2011, two years after Jones left the Senate. It

isn’t clear whether Jones spent campaign money on Bulls tickets,

airfare, hotels, meals and other things in connection with his duties as

chairman of the authority that built and owns U.S. Cellular Field and

also helped with renovations at Soldier Field. If so, those expenditures

wouldn’t deplete the amount collected prior to the 1998 law change that

he is allowed to pocket, so long as he pays income taxes. Shortly after

being sworn in, Gov. Rauner replaced Jones on the sports facility

authority.

But Jones isn’t hurting for money. He still had nearly $230,000 in his campaign fund as of Jan. 1.

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].